The ART Book

Contributed by Peter Bereczky

NOTE: The book was originally written in Hungarian, and it has been translated into English automatically. If you spot errors, inconsistencies, unclear sentences, and so on, consider reporting them as issues on GitHub. The more people will contribute and proof-read the material, the more useful it will become for the community!

The original Hungarian version of the book can be found here.

Table of Contents

Legal information

Sources

Recommendation

1. Introduction

2. Basic knowledge

2.1 The raw file

2.2 Demosaicing

2.3 Raw black level, Raw white level

2.4 Color management, color systems

2.4.1 Two types of frameworks

2.4.2 The CIE XYZ 1931 color system

2.4.3 RGB color system

2.4.4 CYMK color system

2.4.5 HSV color system

2.4.6 LCH Color System

2.4.7 CIELAB or L*a*b*

2.4.8 Hue, color wheel

2.4.9 Terms used when describing and modifying colors

2.5 Tones

2.6 Dynamic range (tonal range), contrast

2.7 Opacity

2.8 Feather

2.9 Wavelet decomposition

2.10 Capture sharpening procedures

2.11 Noisy images

2.12 Artifacts in the image

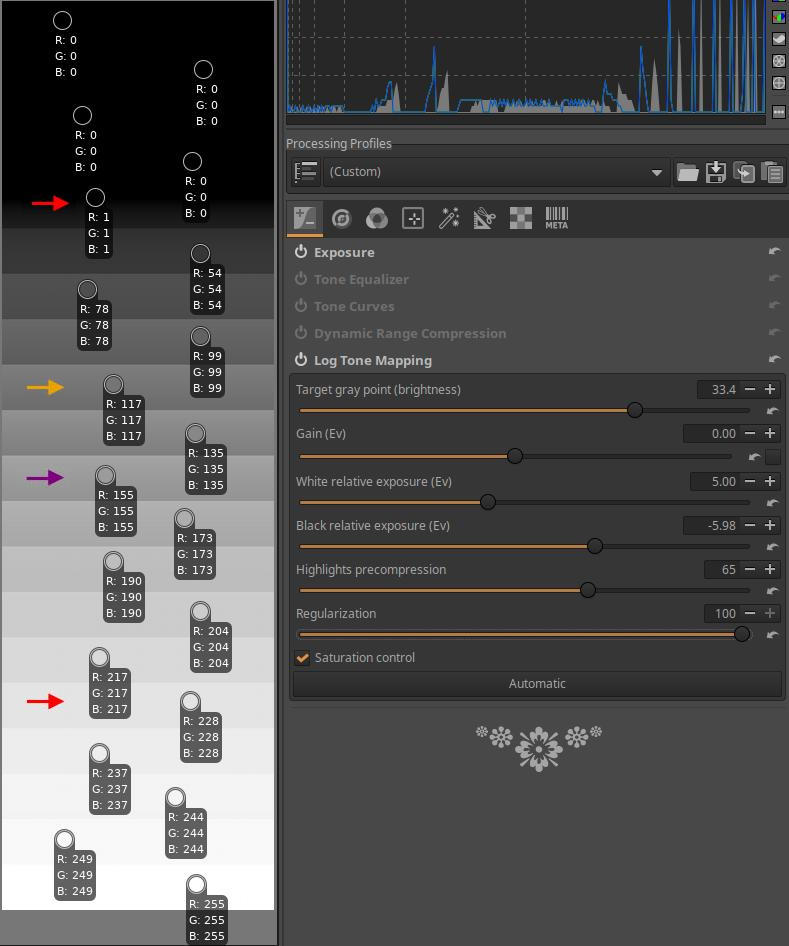

2.13 The mid.tif image

2.14 Recommended computer configuration

2.15 What monitor should we use?

2.16 How do we get lens profiles and camera profiles?

3. The ART raw file processing program

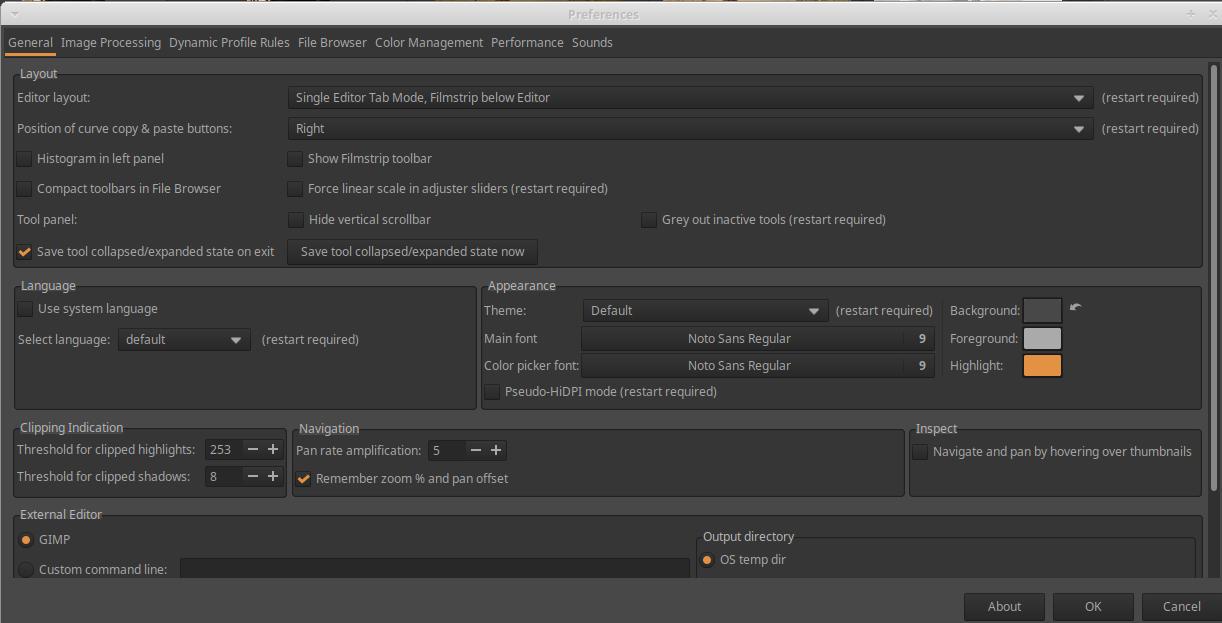

3.1 Overview

3.2 ART website

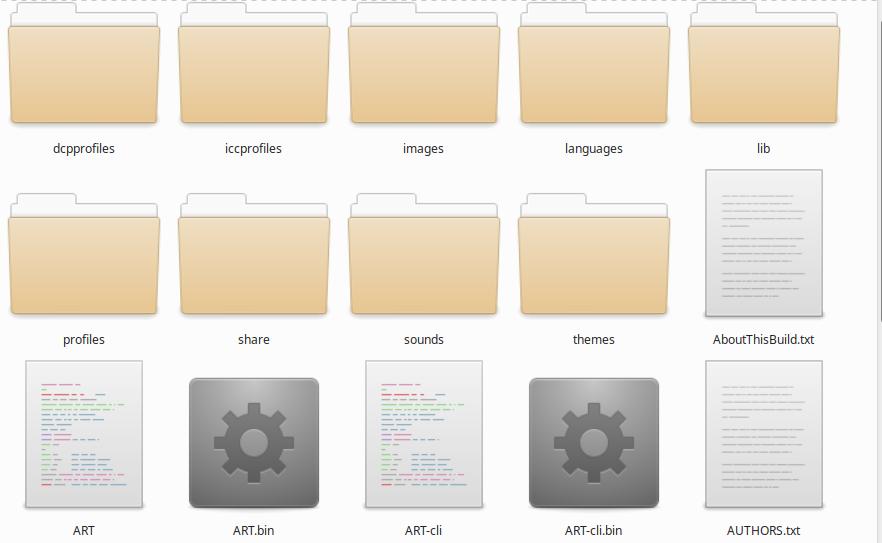

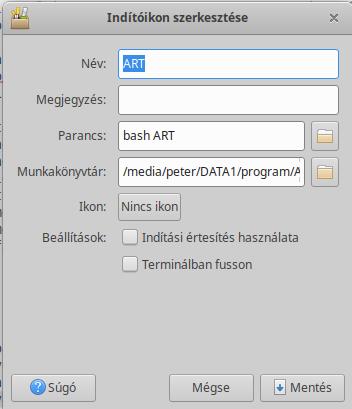

3.3 Installing ART

3.4 Non-destructive processing

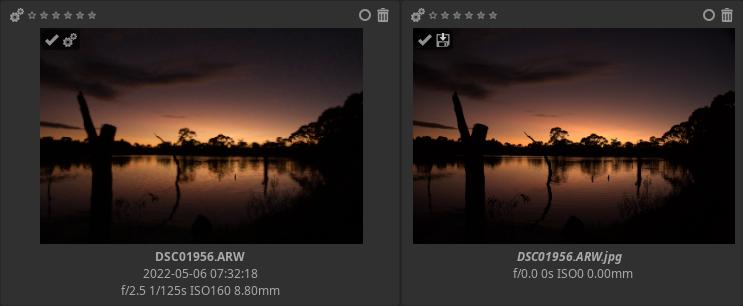

3.5 Sidecar files

3.6 The ART’s pipeline

3.7 Three basic views of ART

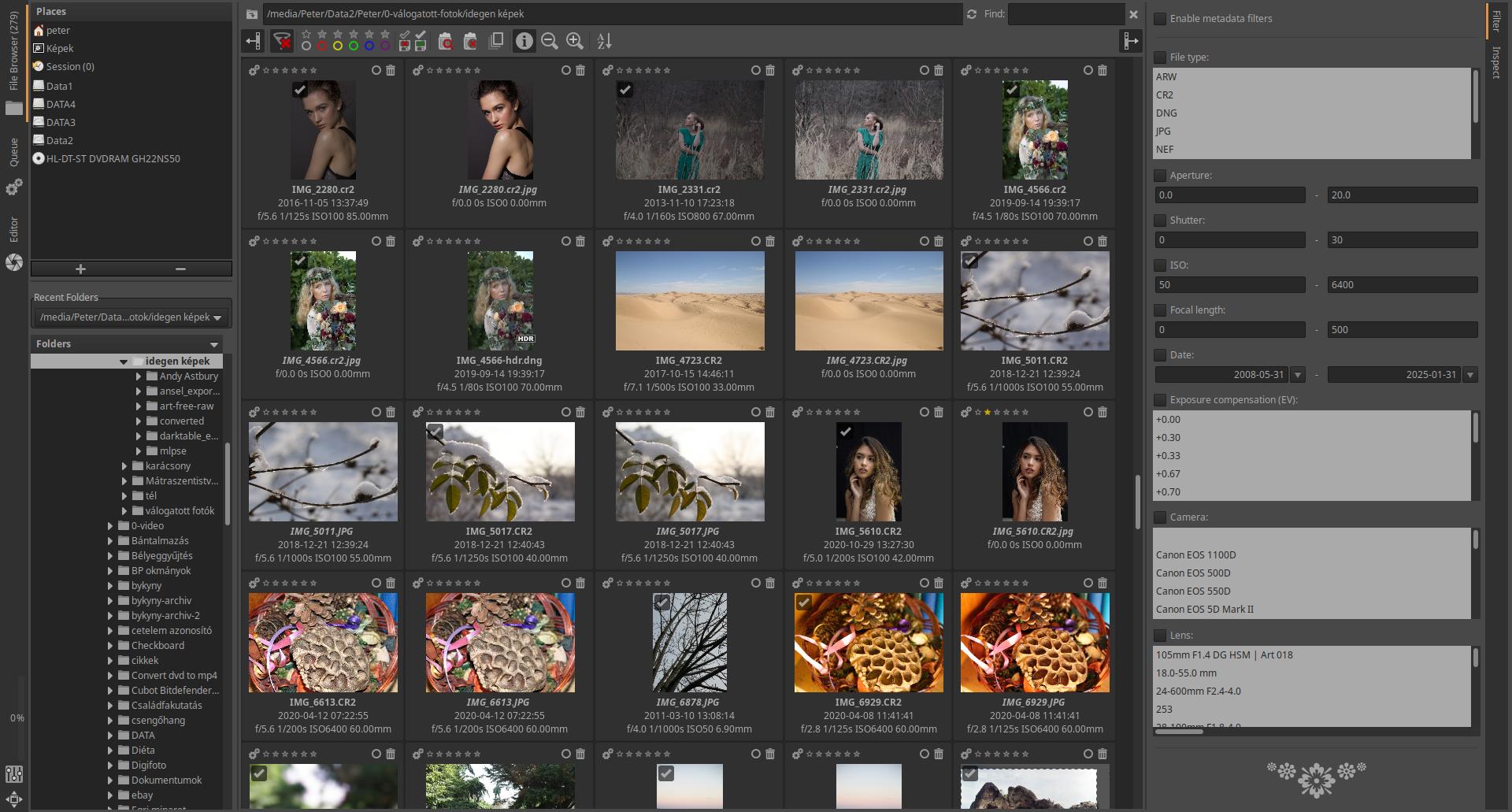

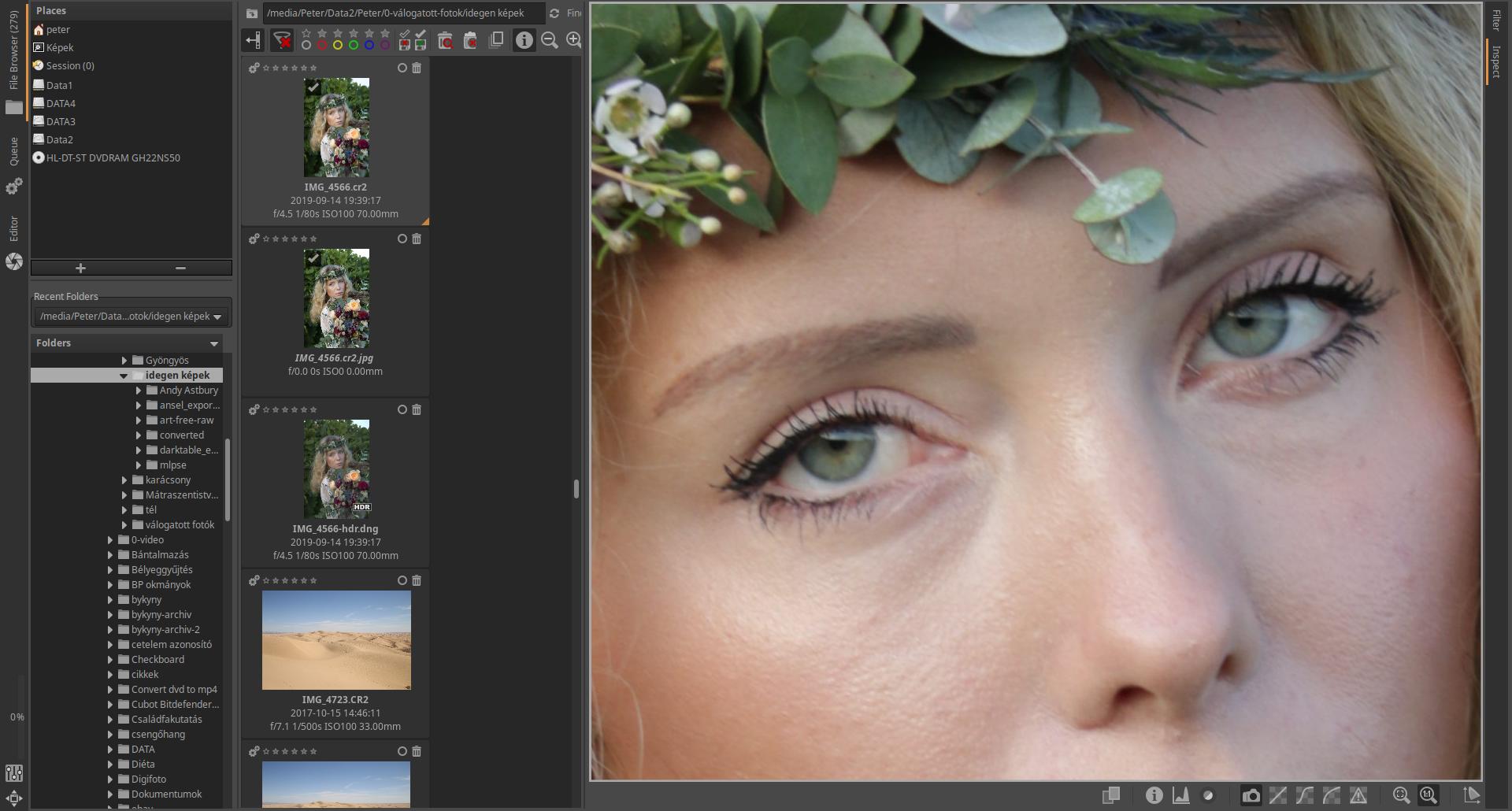

3.8 File browser

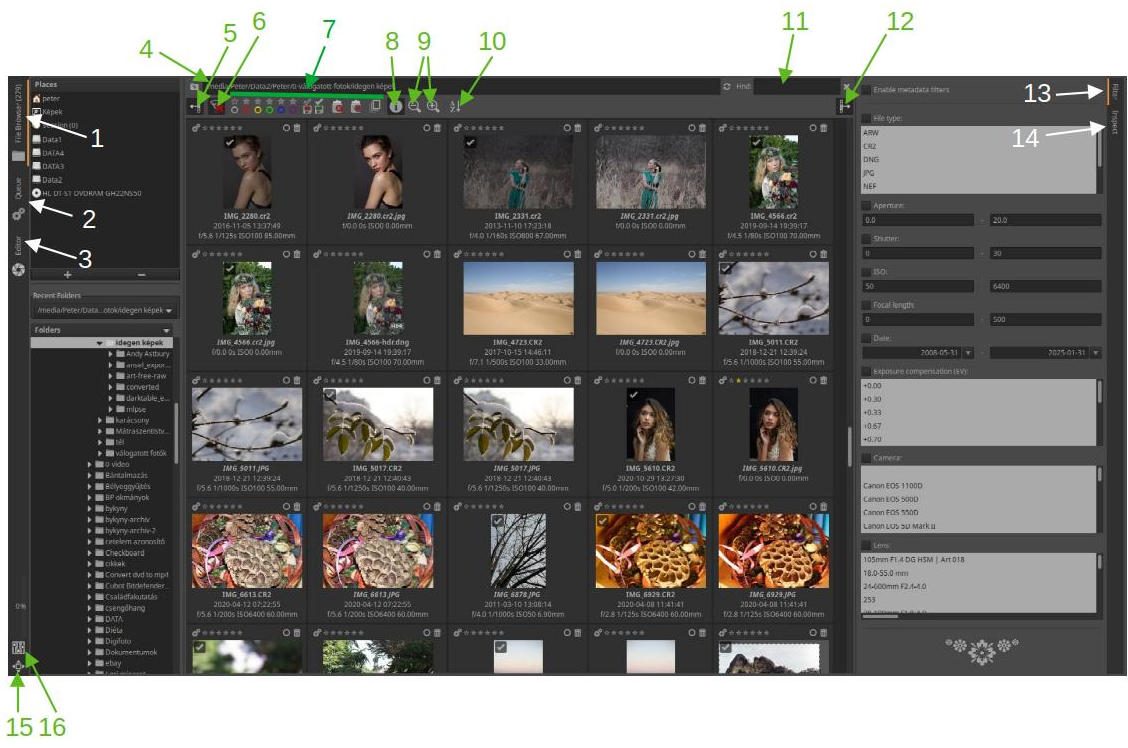

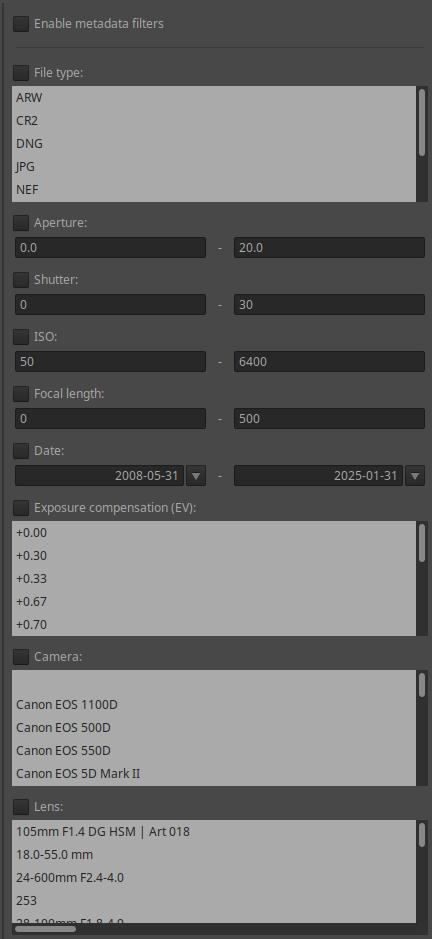

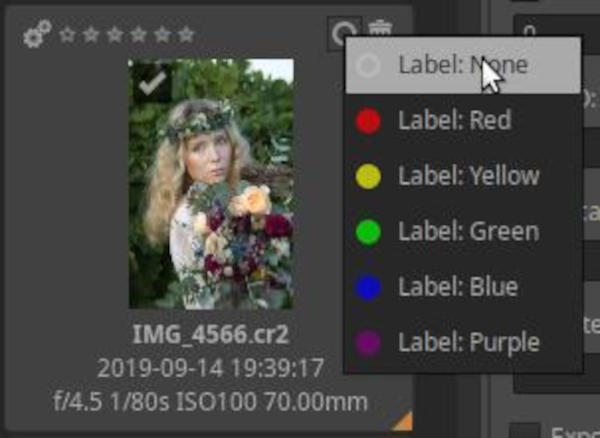

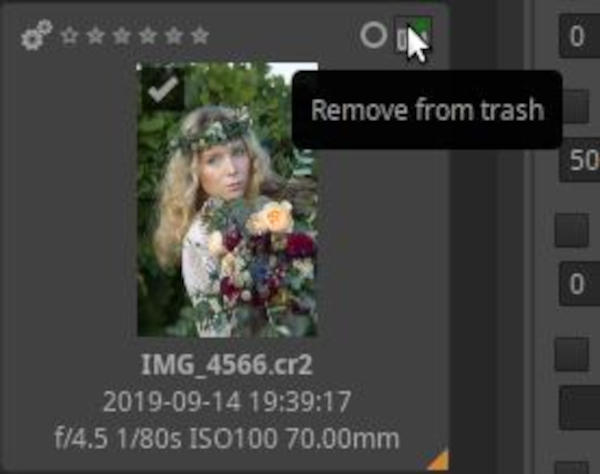

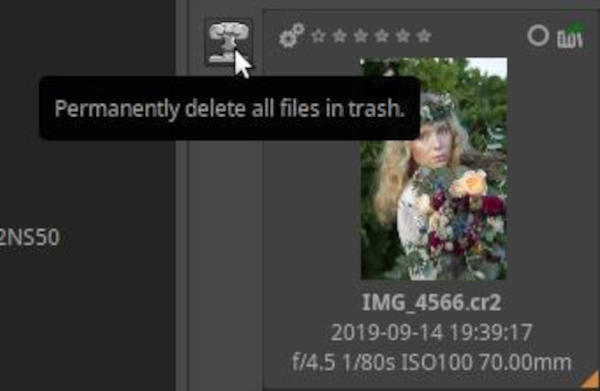

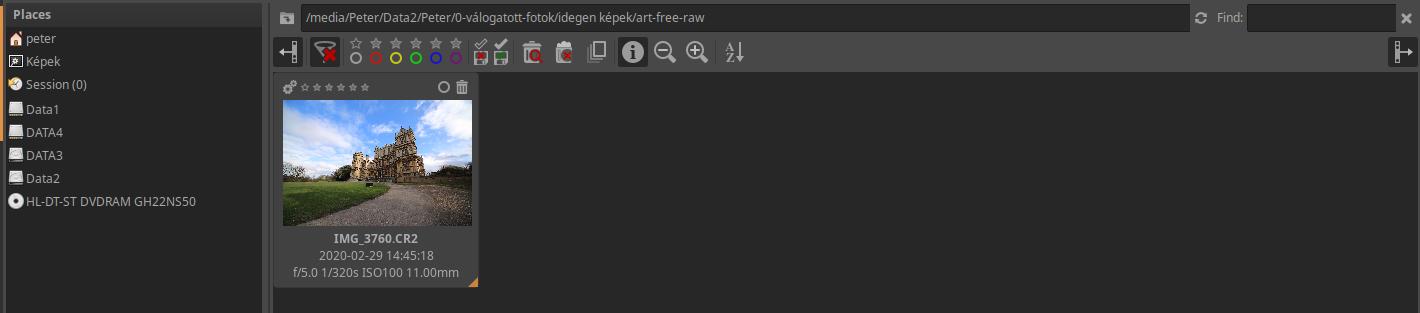

3.8.1 File browser user interface

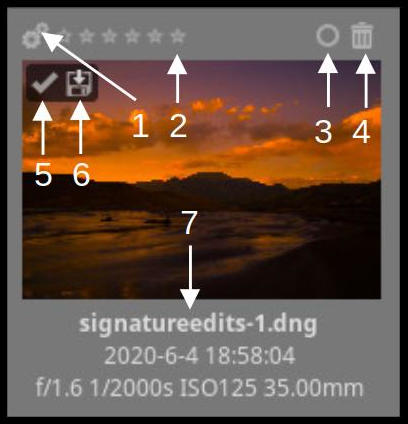

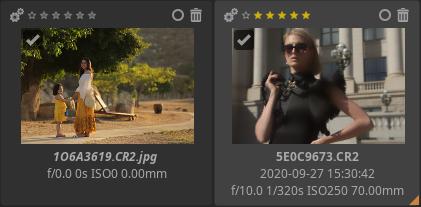

3.8.2 Thumbnails

3.8.3 Update thumbnails

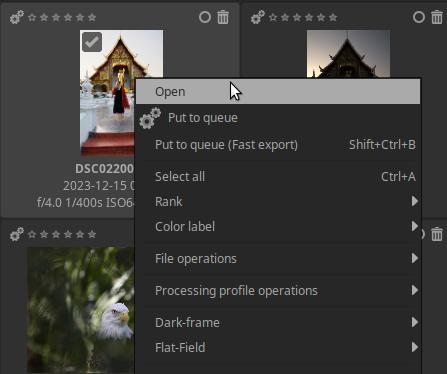

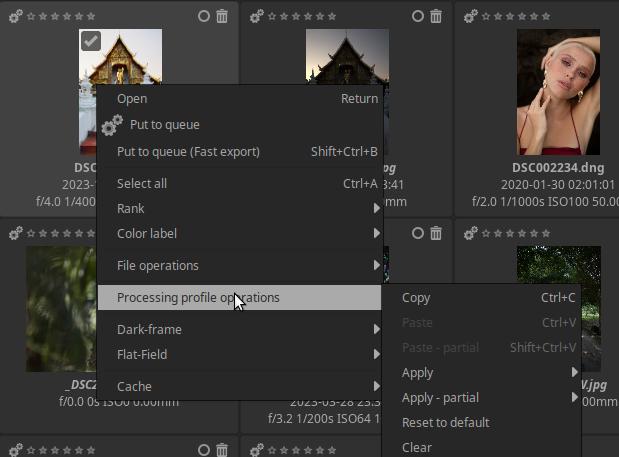

3.8.4 Context menu

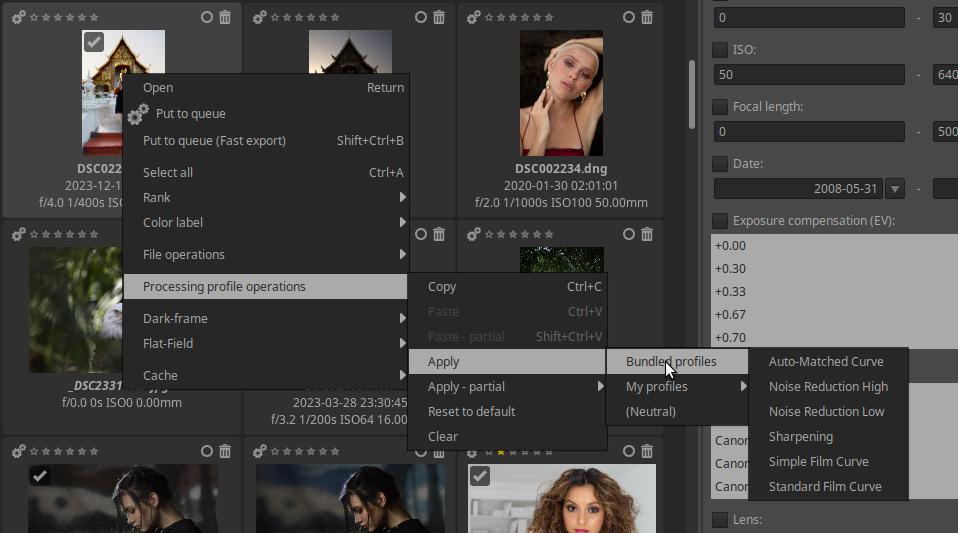

3.8.5 Processing profile operations

3.8.6 Sessions

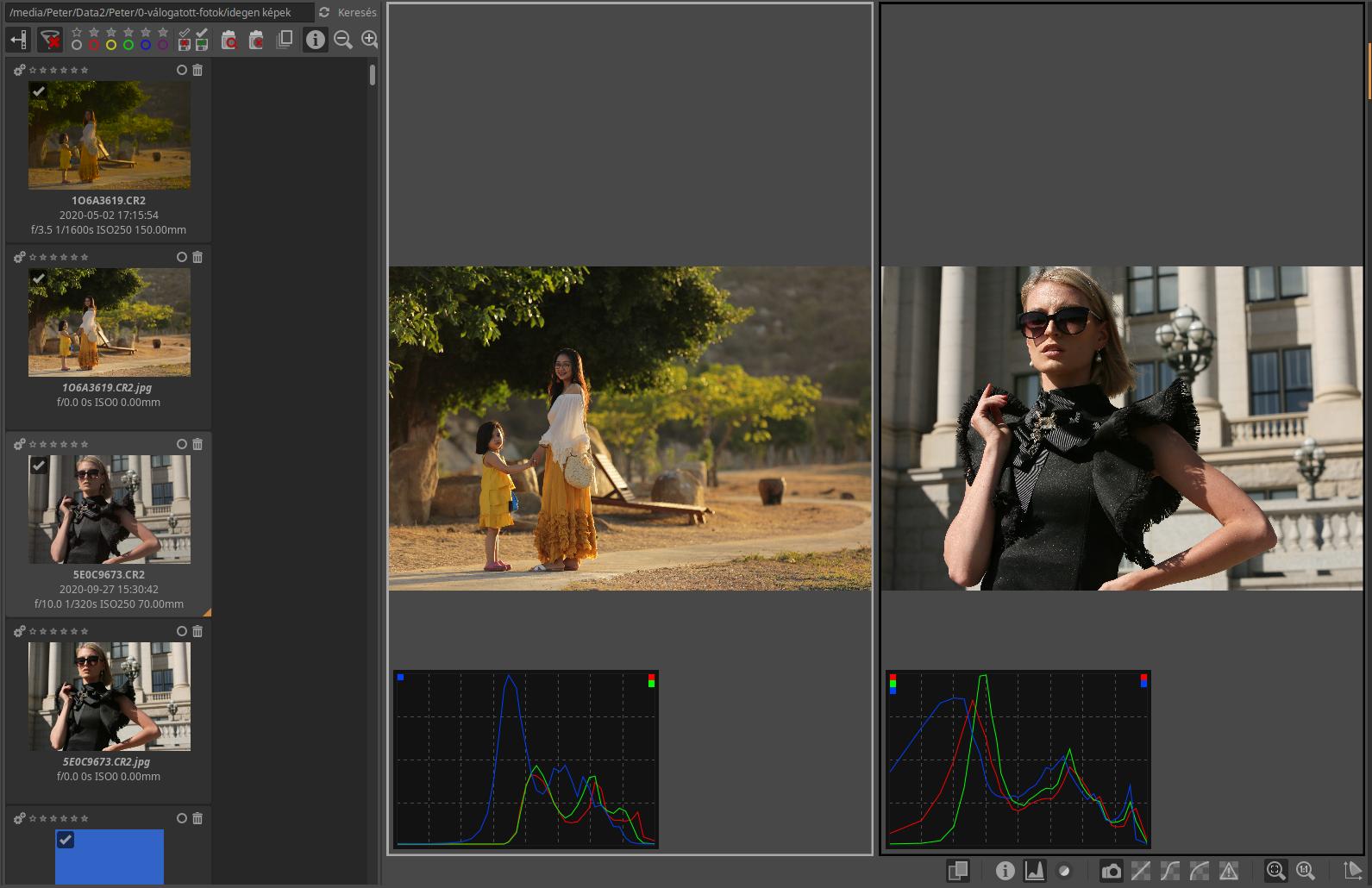

3.9 Inspect

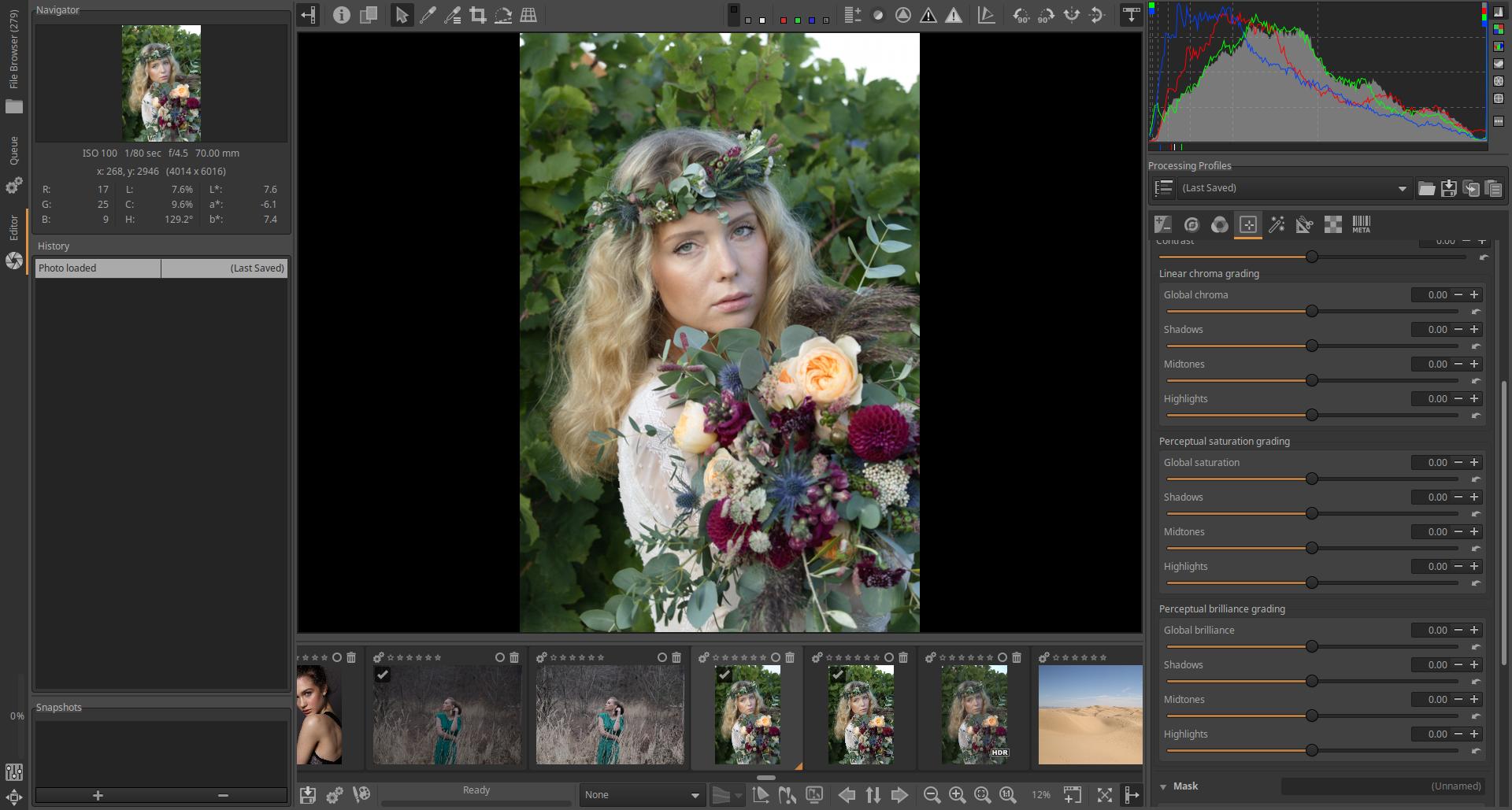

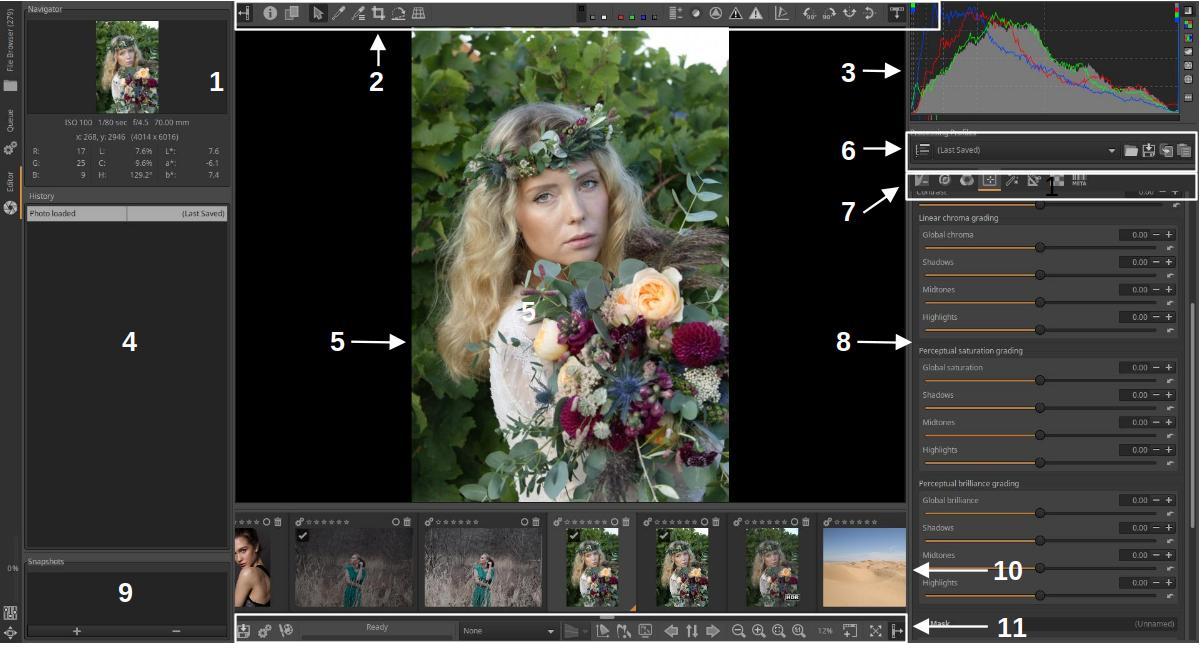

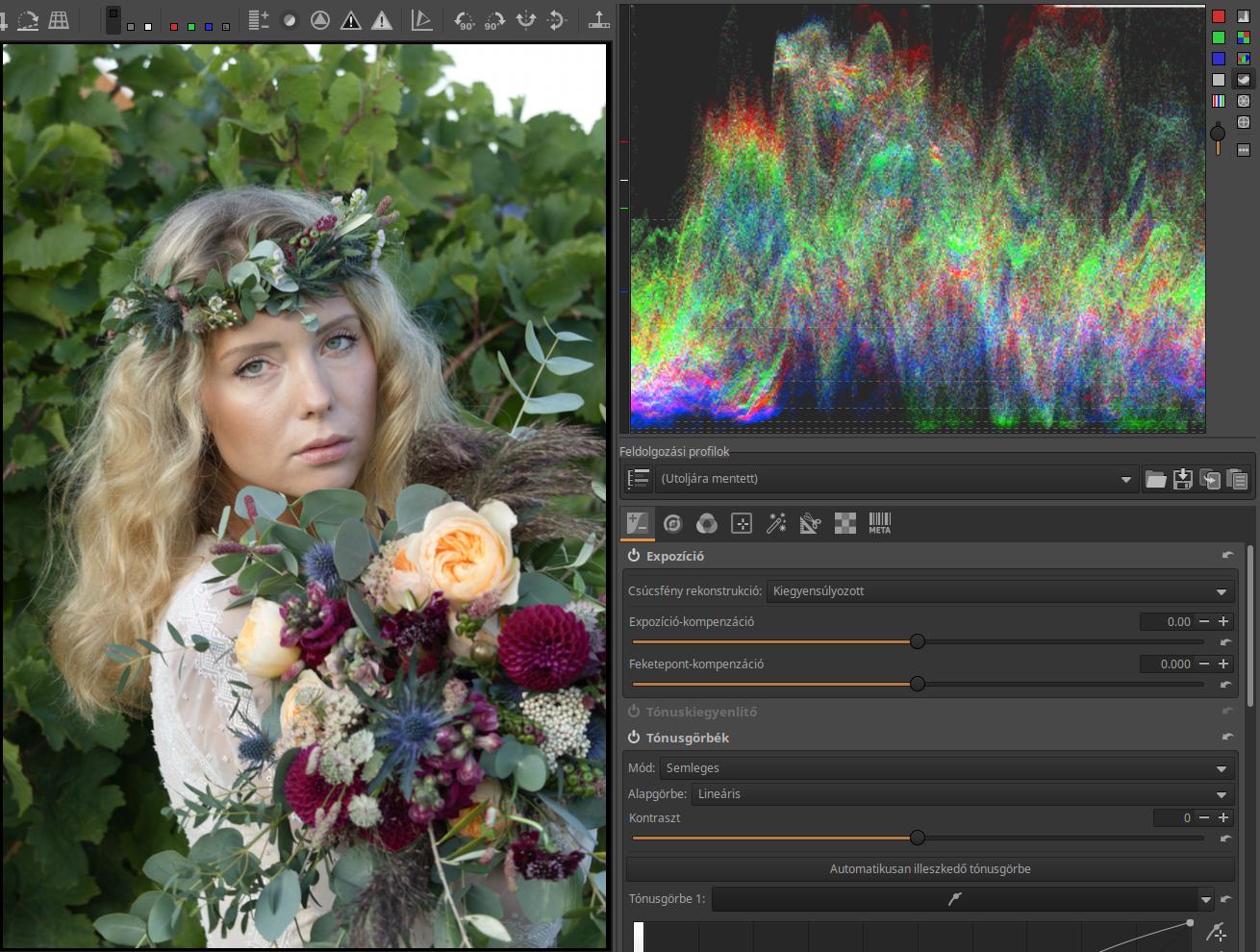

3.10 Editor

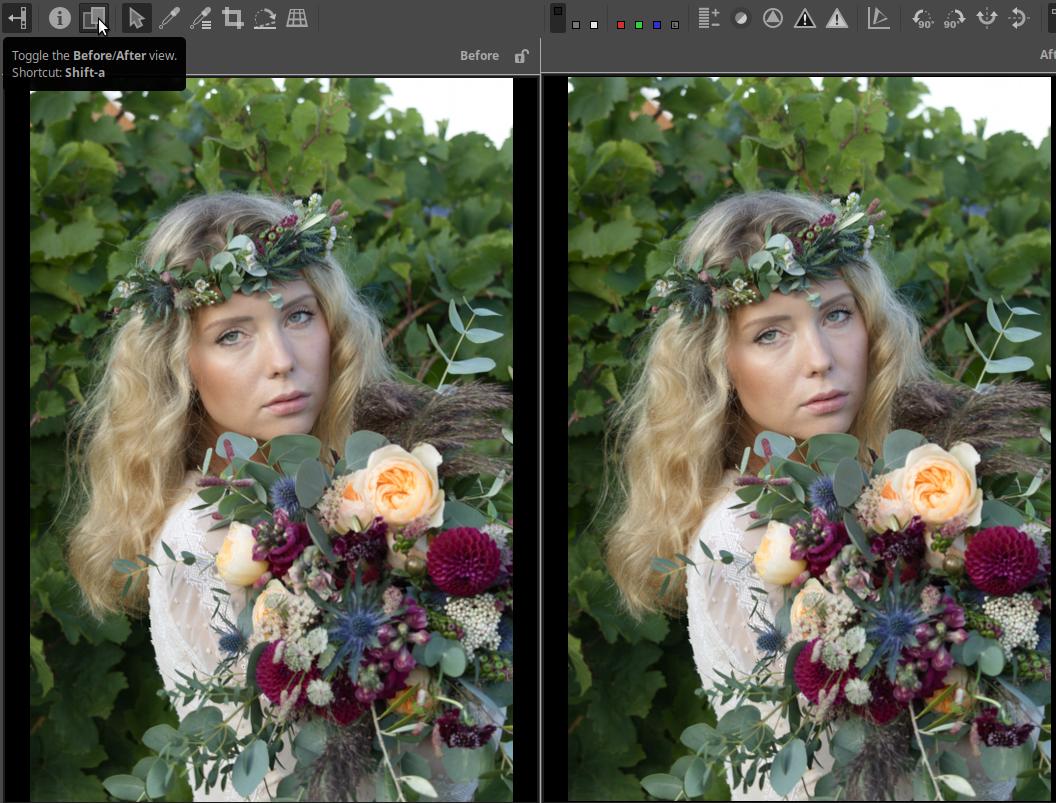

3.10.1 Preview

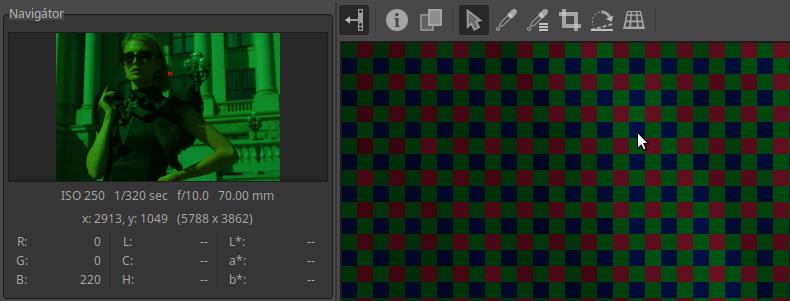

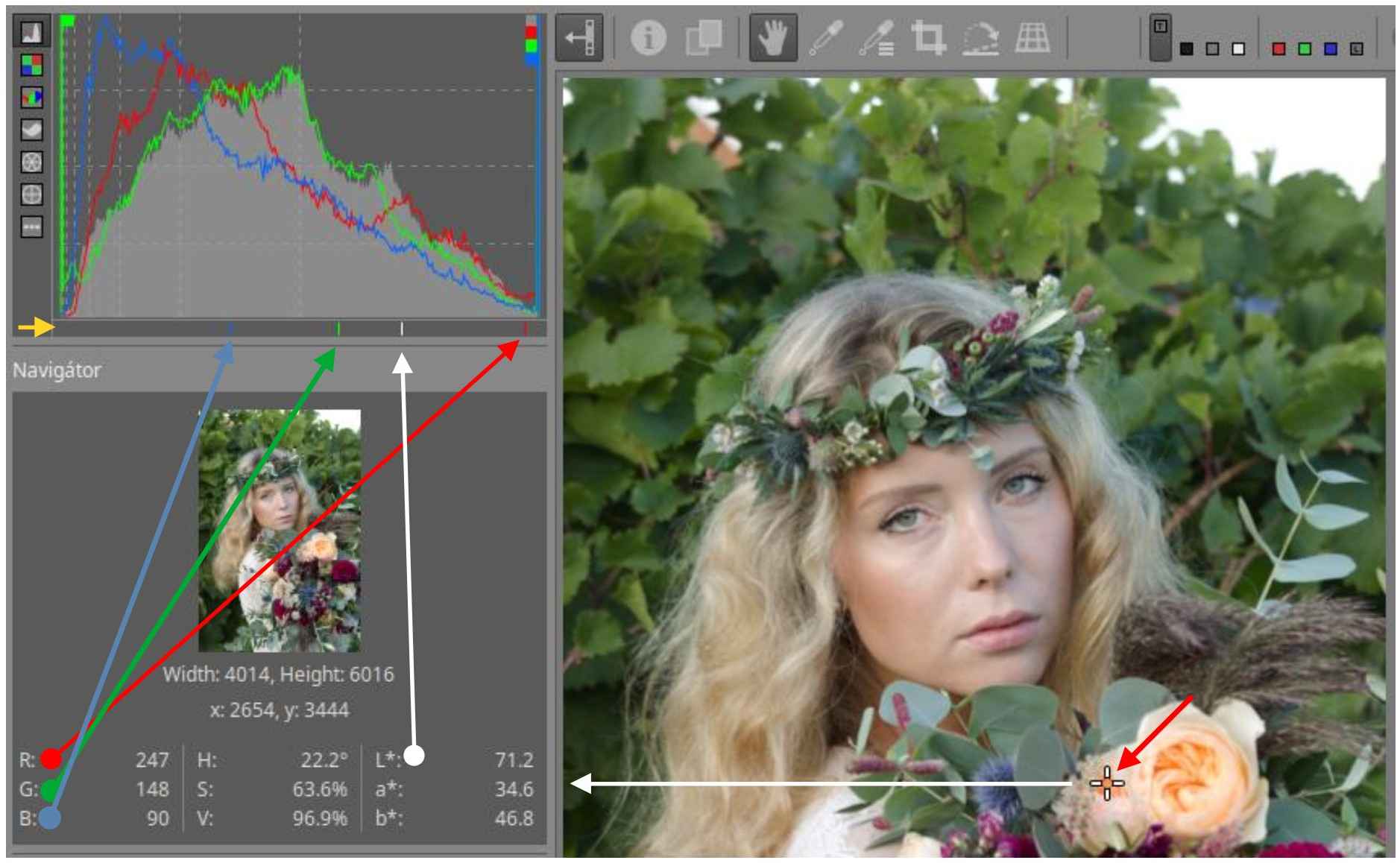

3.10.2 Navigator

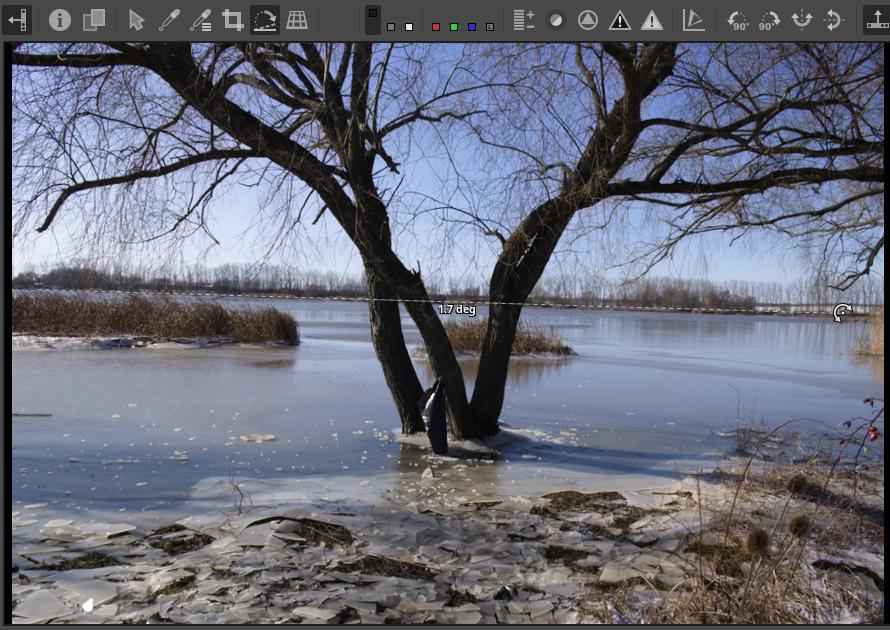

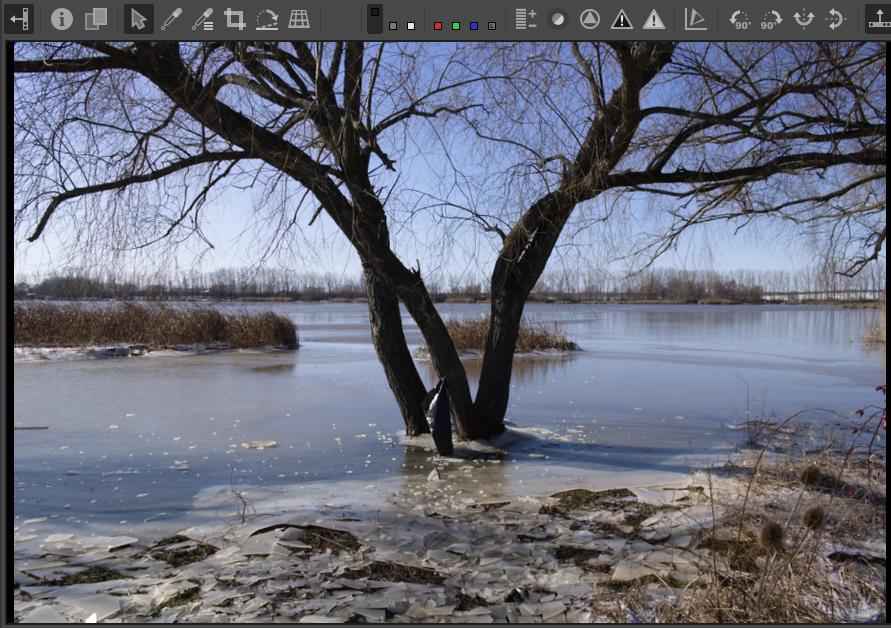

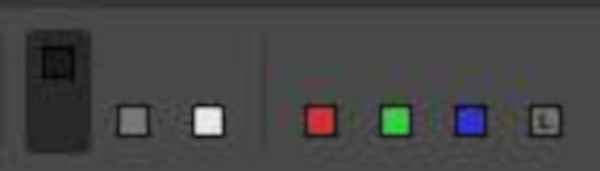

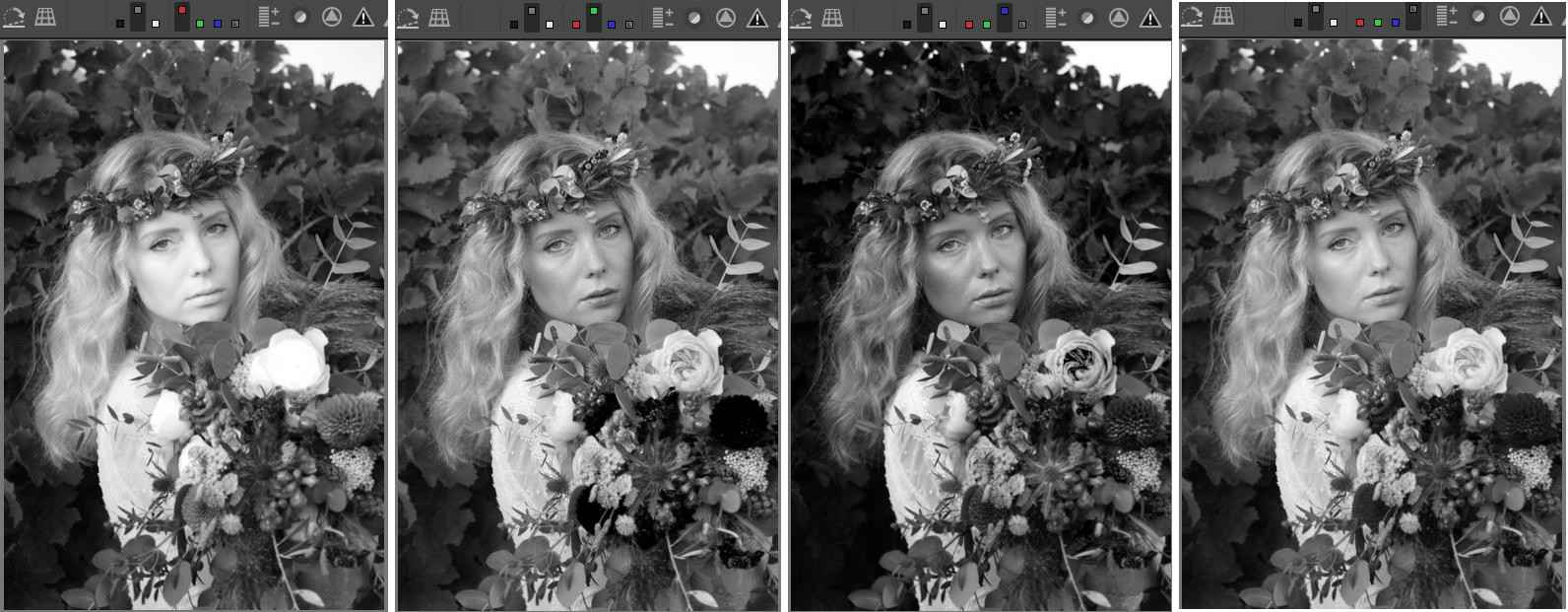

3.10.3 Top toolbar

3.10.4 Histogram

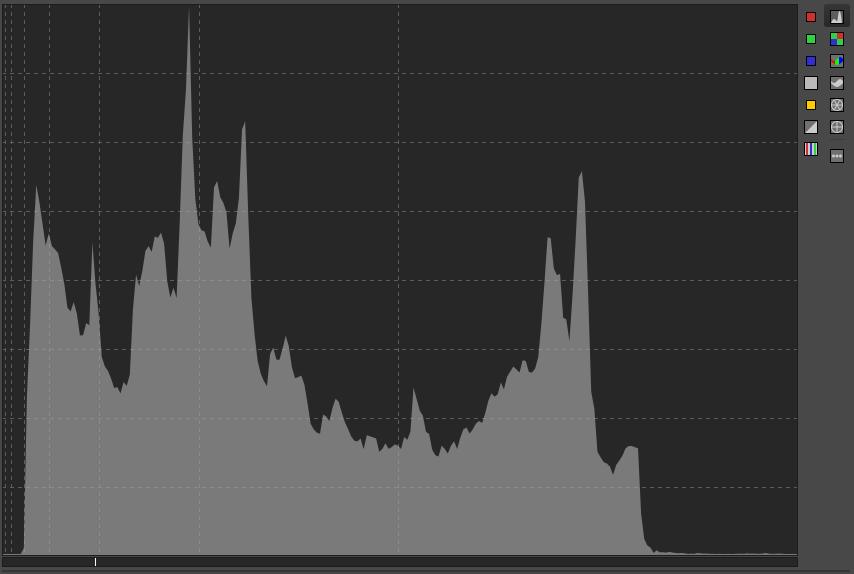

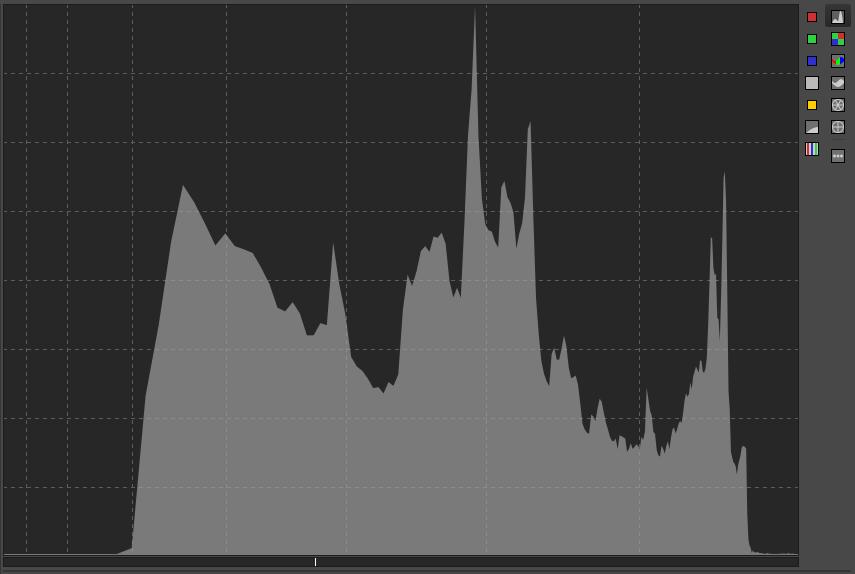

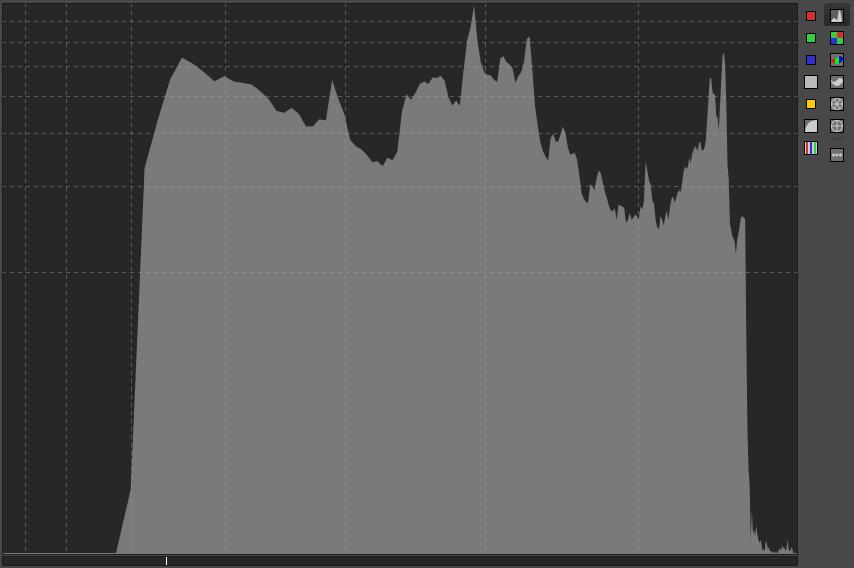

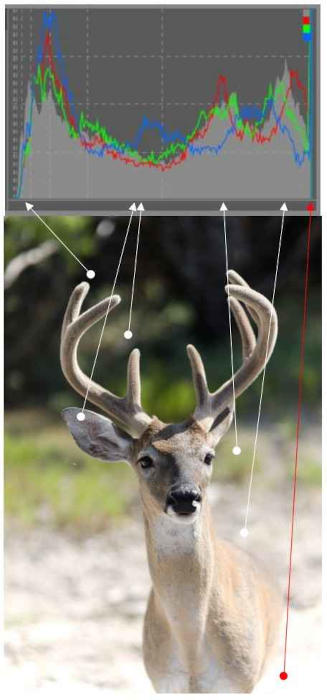

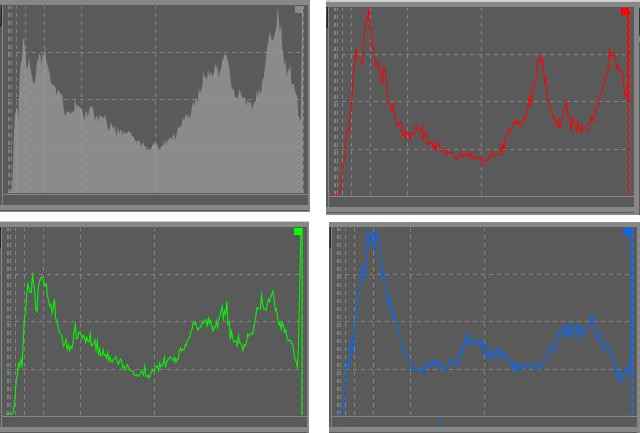

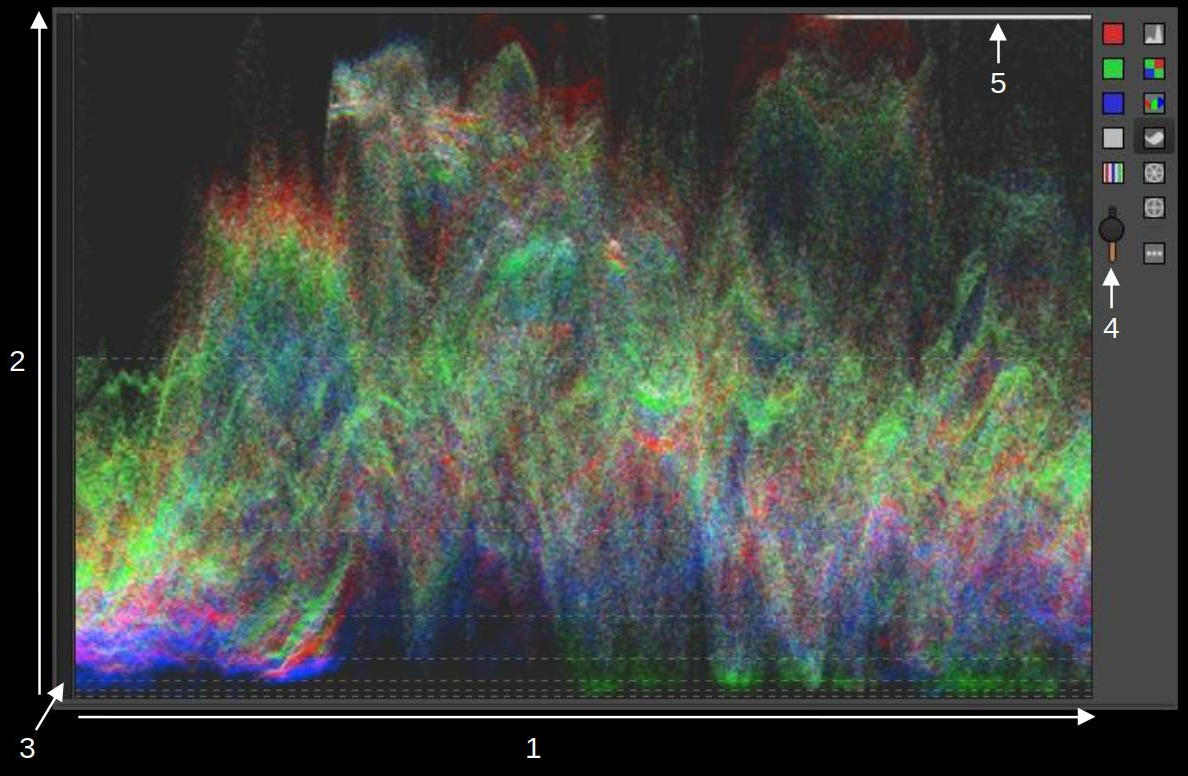

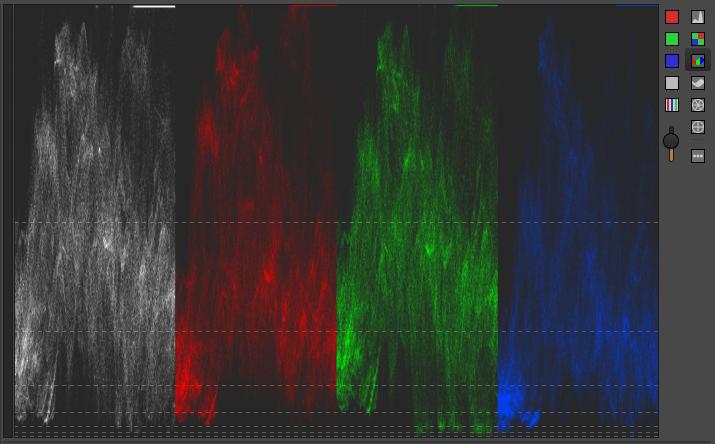

3.10.4.1 Main histogram

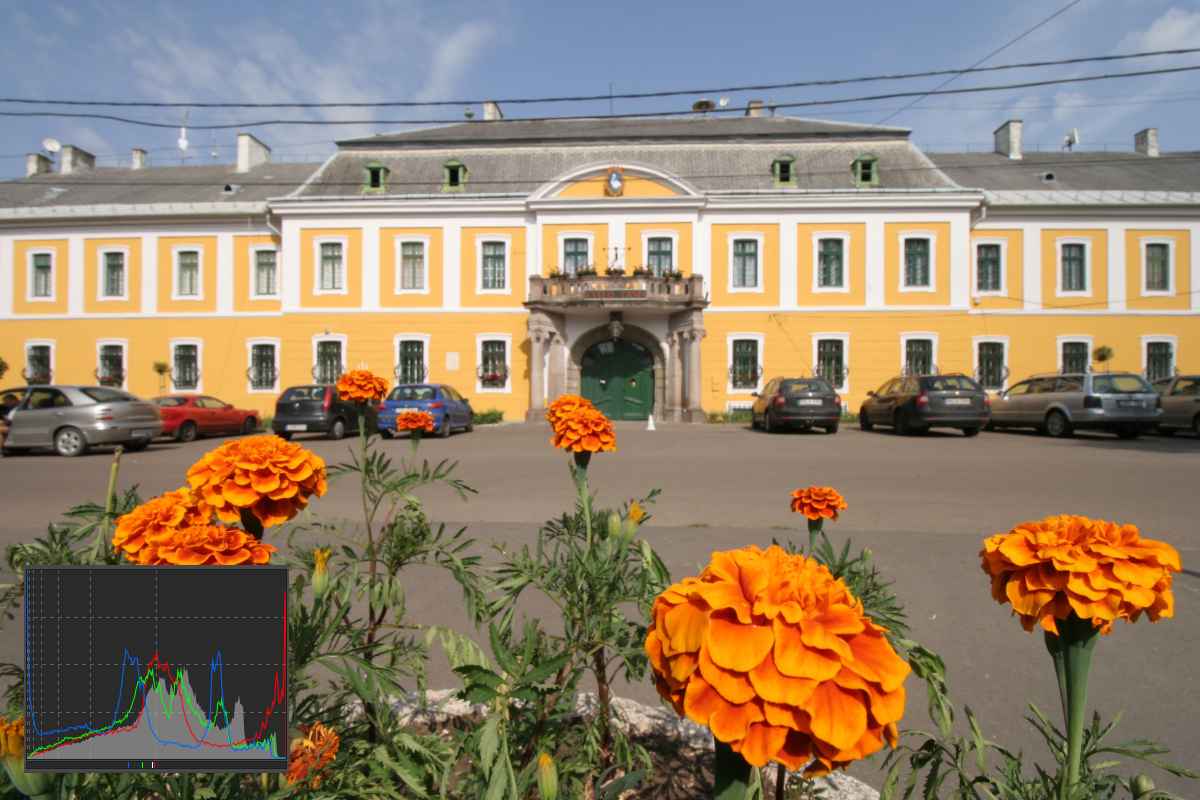

3.10.4.2 The image and its histogram

3.10.4.3 Interaction between preview, navigator, and histogram

3.10.4.4 Determining the reason for the cut

3.10.4.5 Waveform

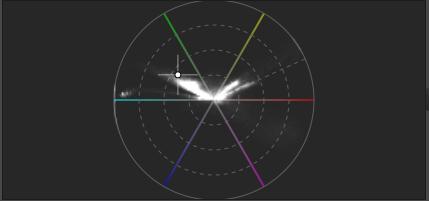

3.10.4.6 Vectorscopes

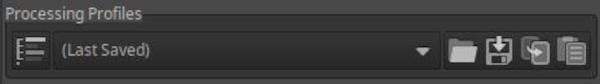

3.10.5 Processing profiles panel

3.10.6 Editing tool groups

3.10.7 Editing tool header

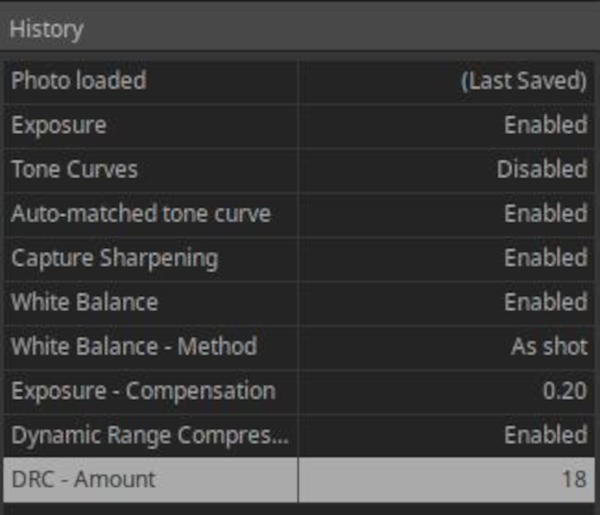

3.10.8 History

3.10.9 Snapshots

3.10.10 Filmstrip

3.10.11 Bottom toolbar

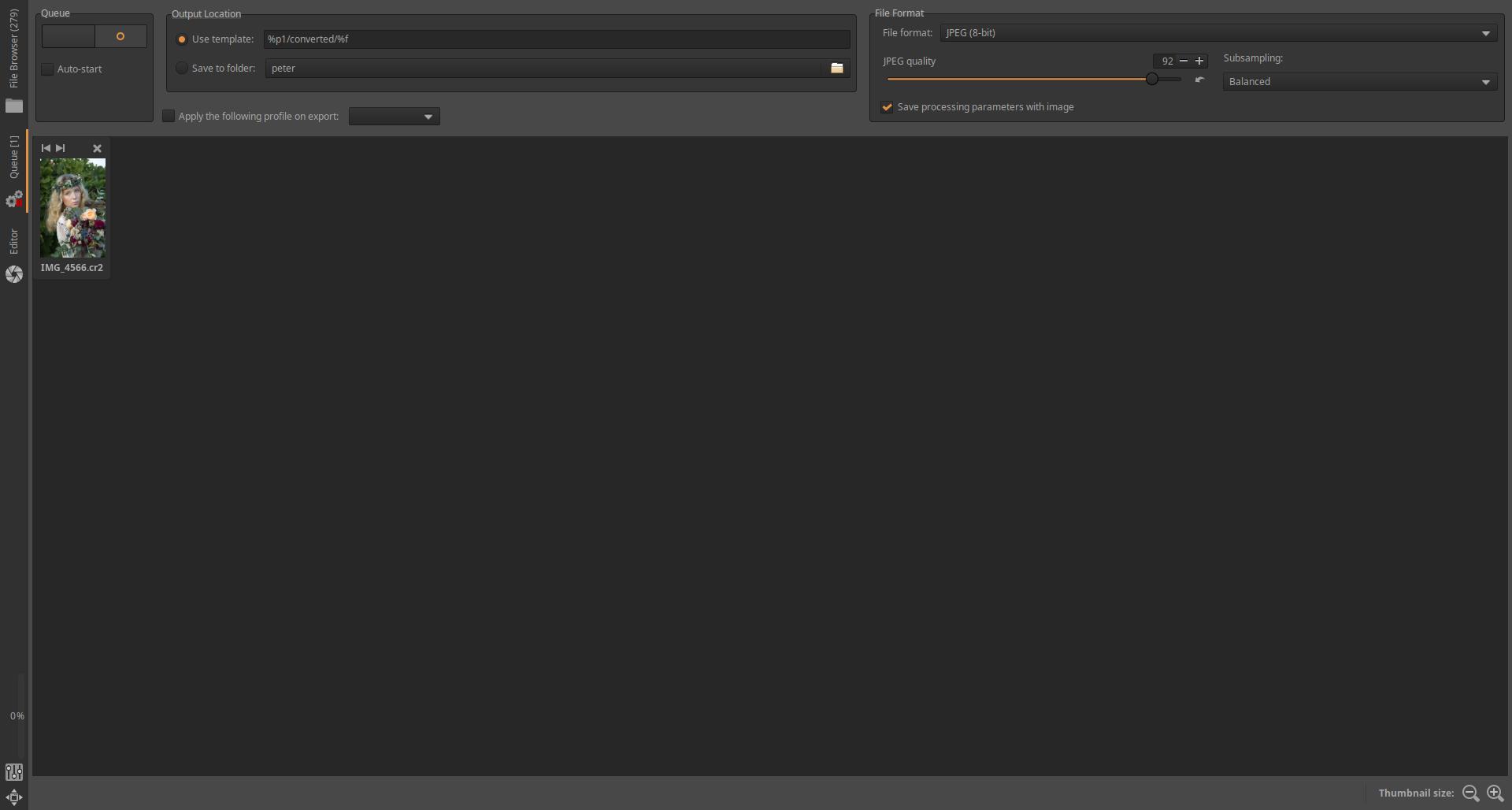

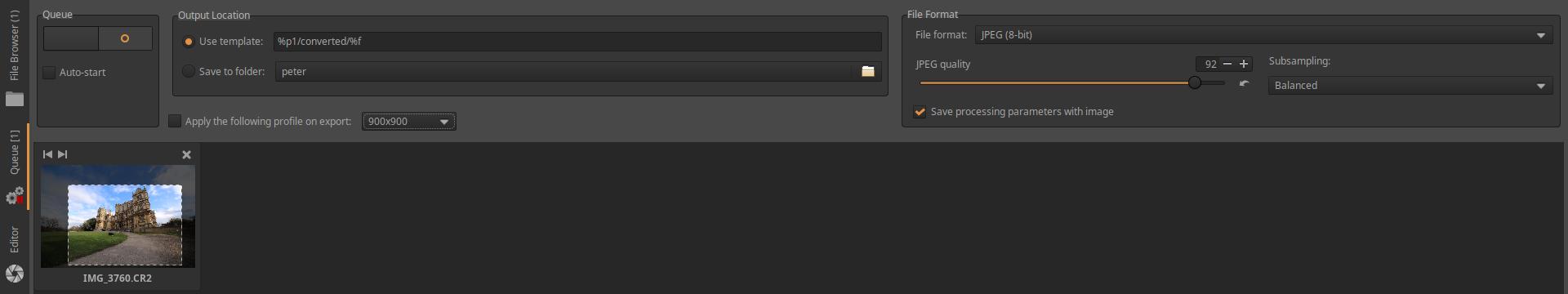

3.11 Queue view

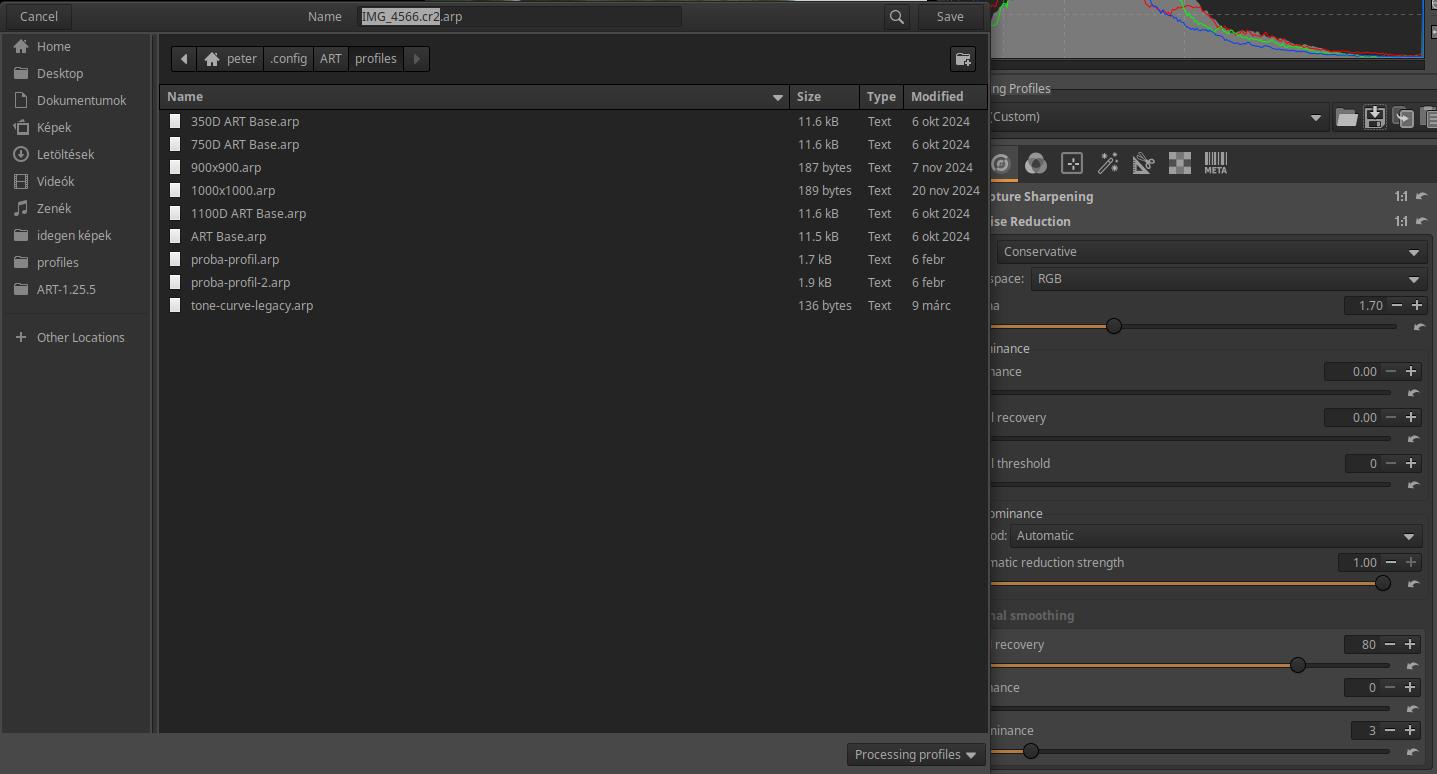

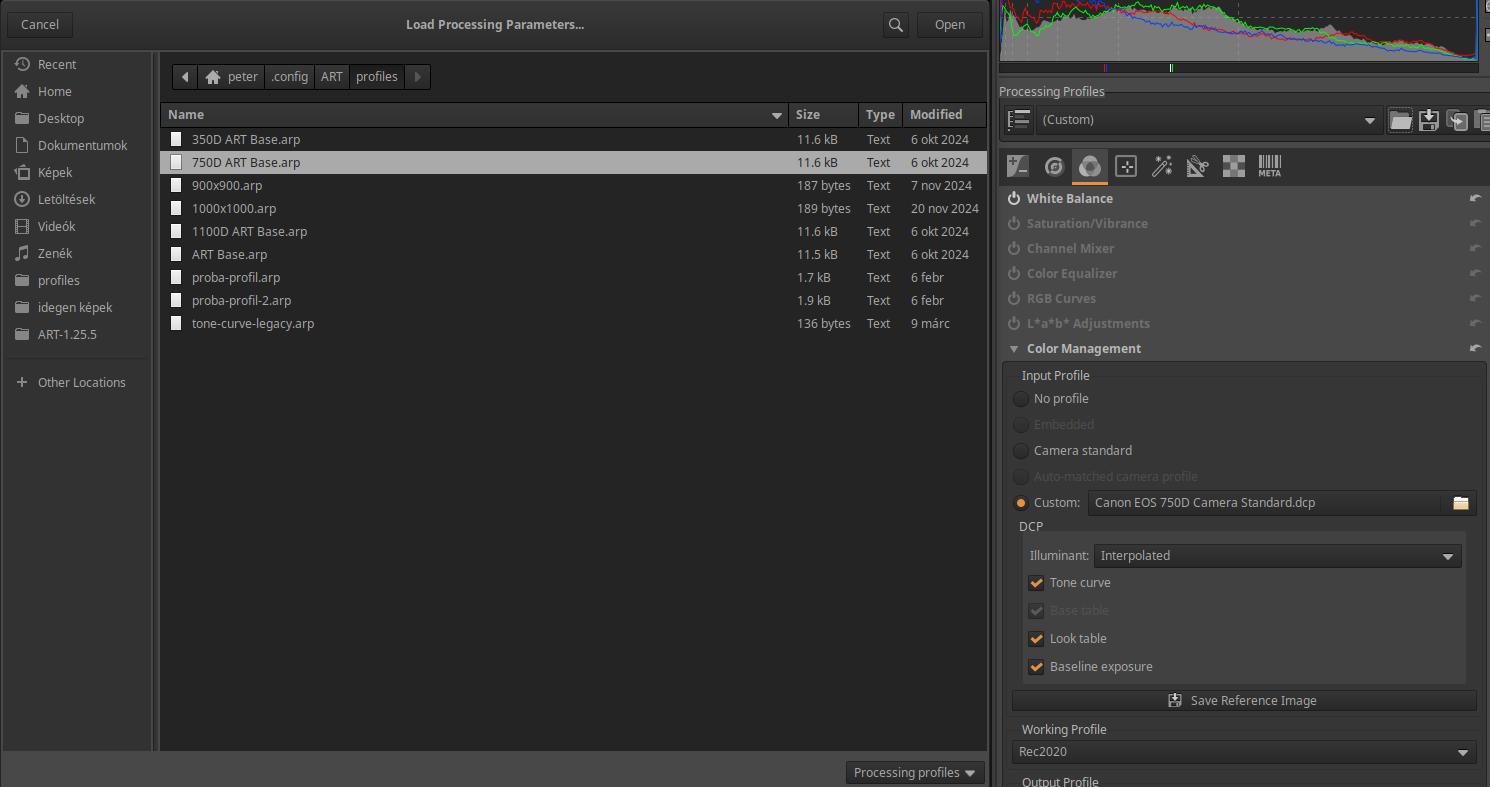

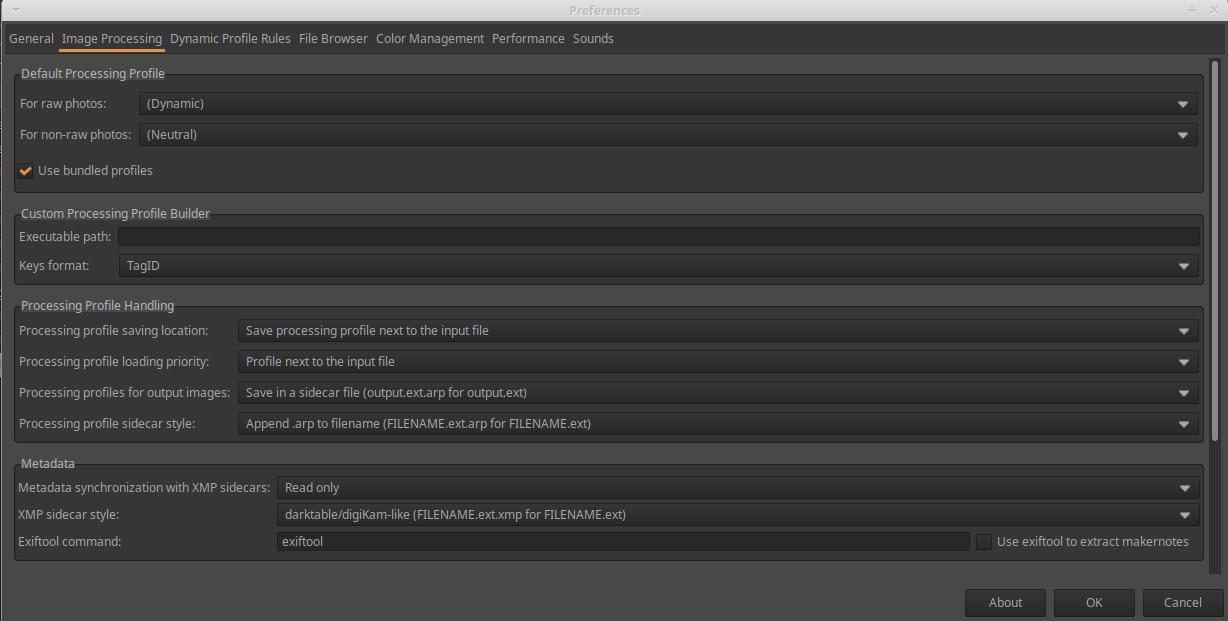

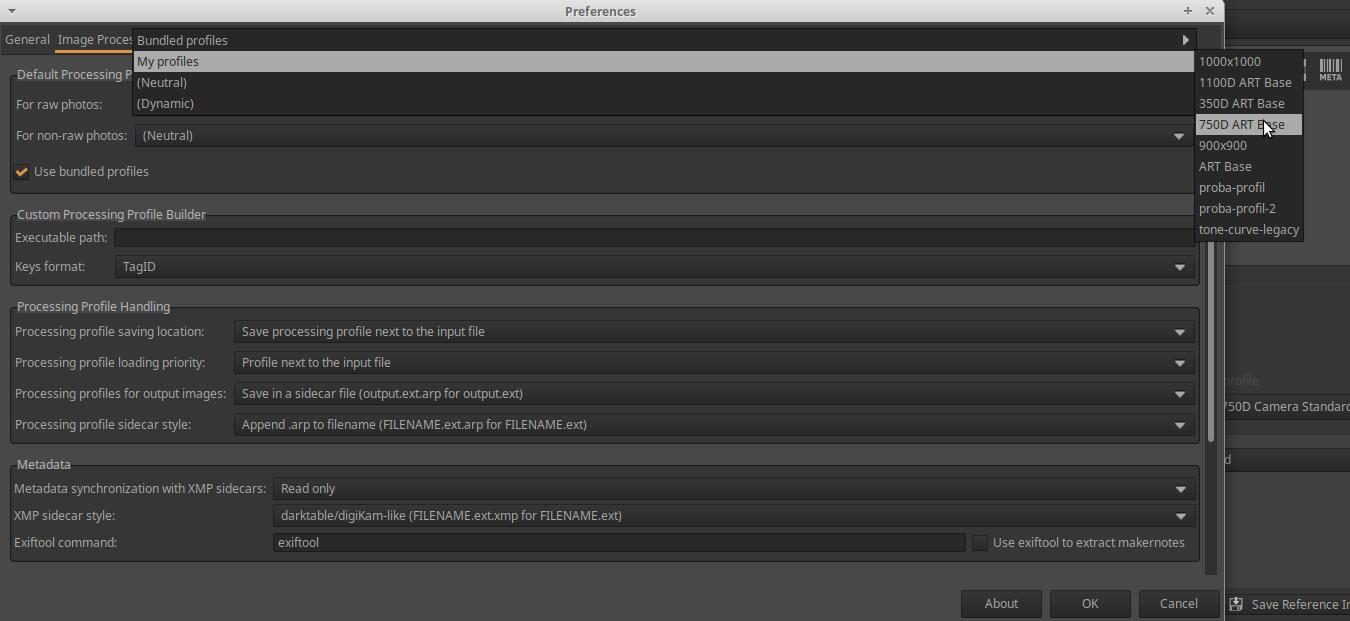

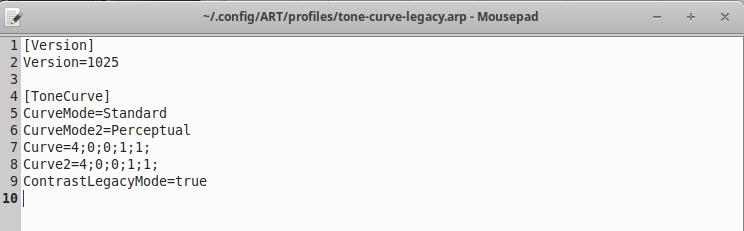

3.12 Processing profiles

3.13 Creating processing profiles

3.13.1 Create a default processing profile

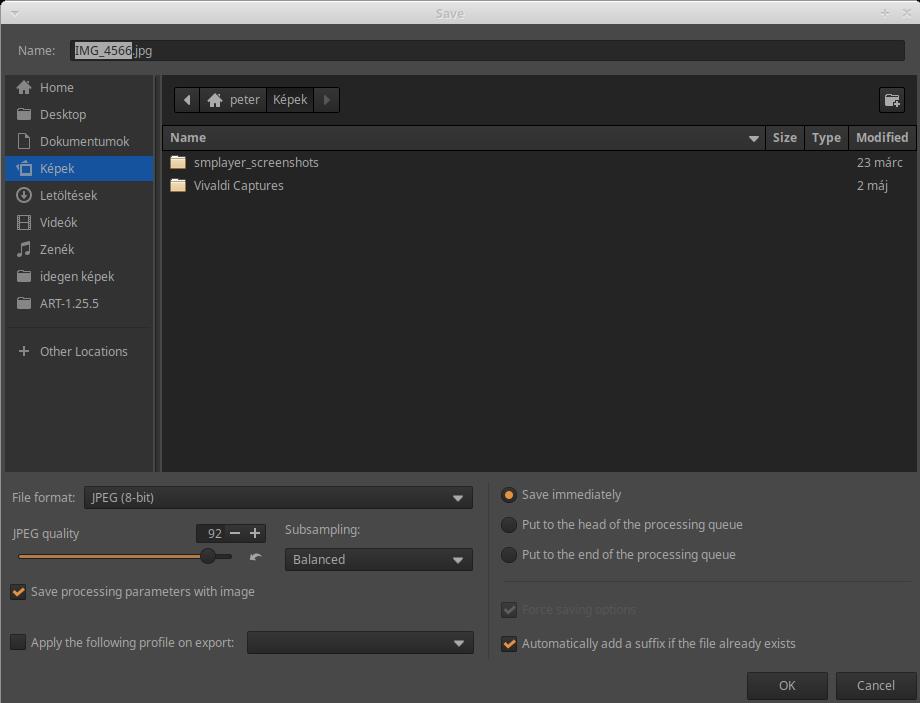

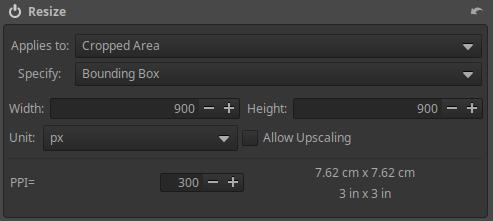

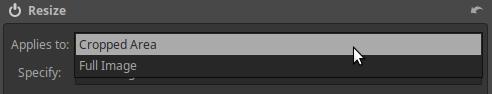

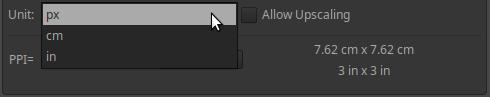

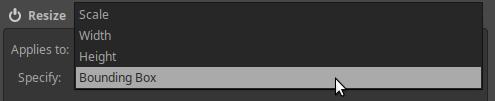

3.13.2 Resizing images

3.13.3 Apply processing profile saved with image file

3.14 Sliders, curve editors

3.14.1 Sliders

3.14.2 Curve editors

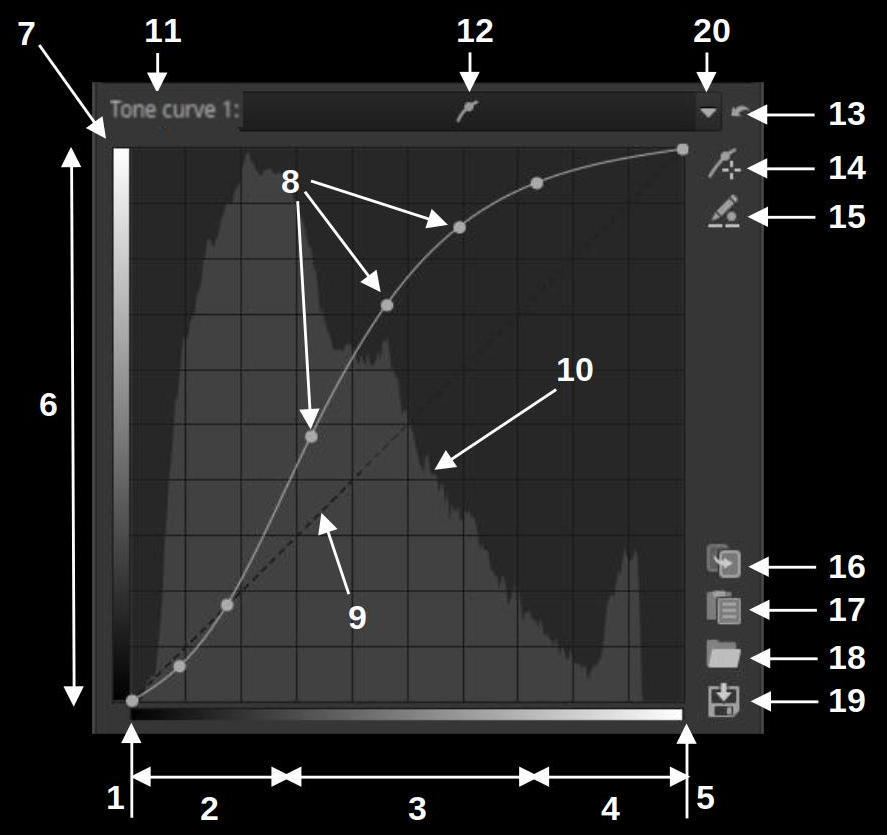

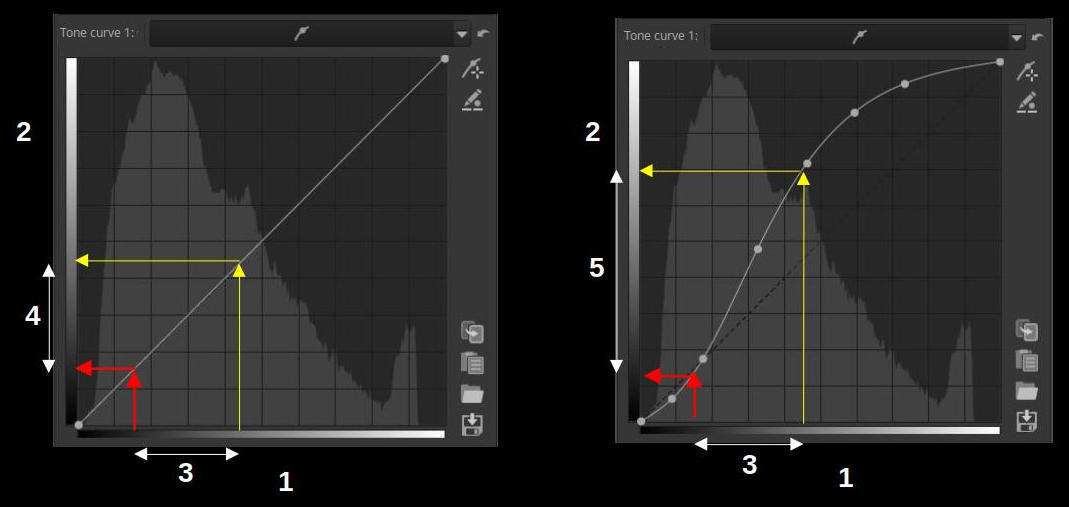

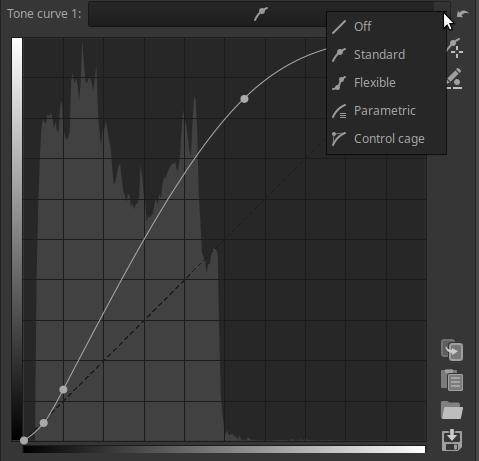

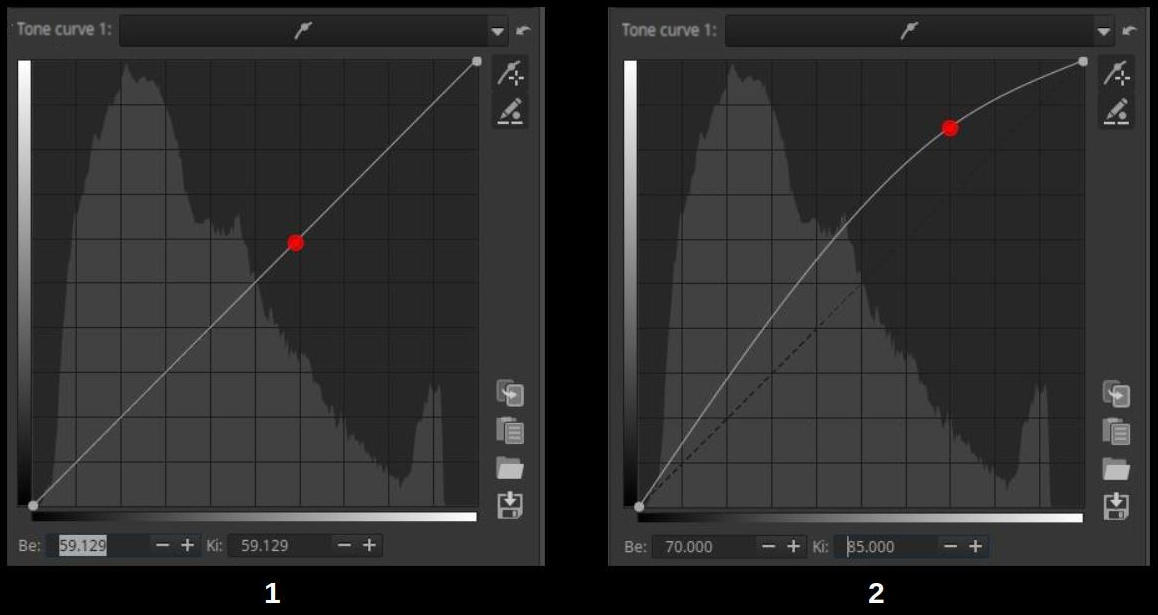

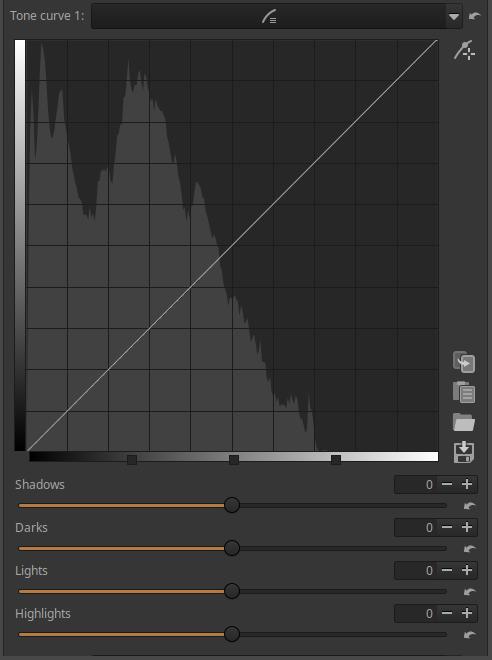

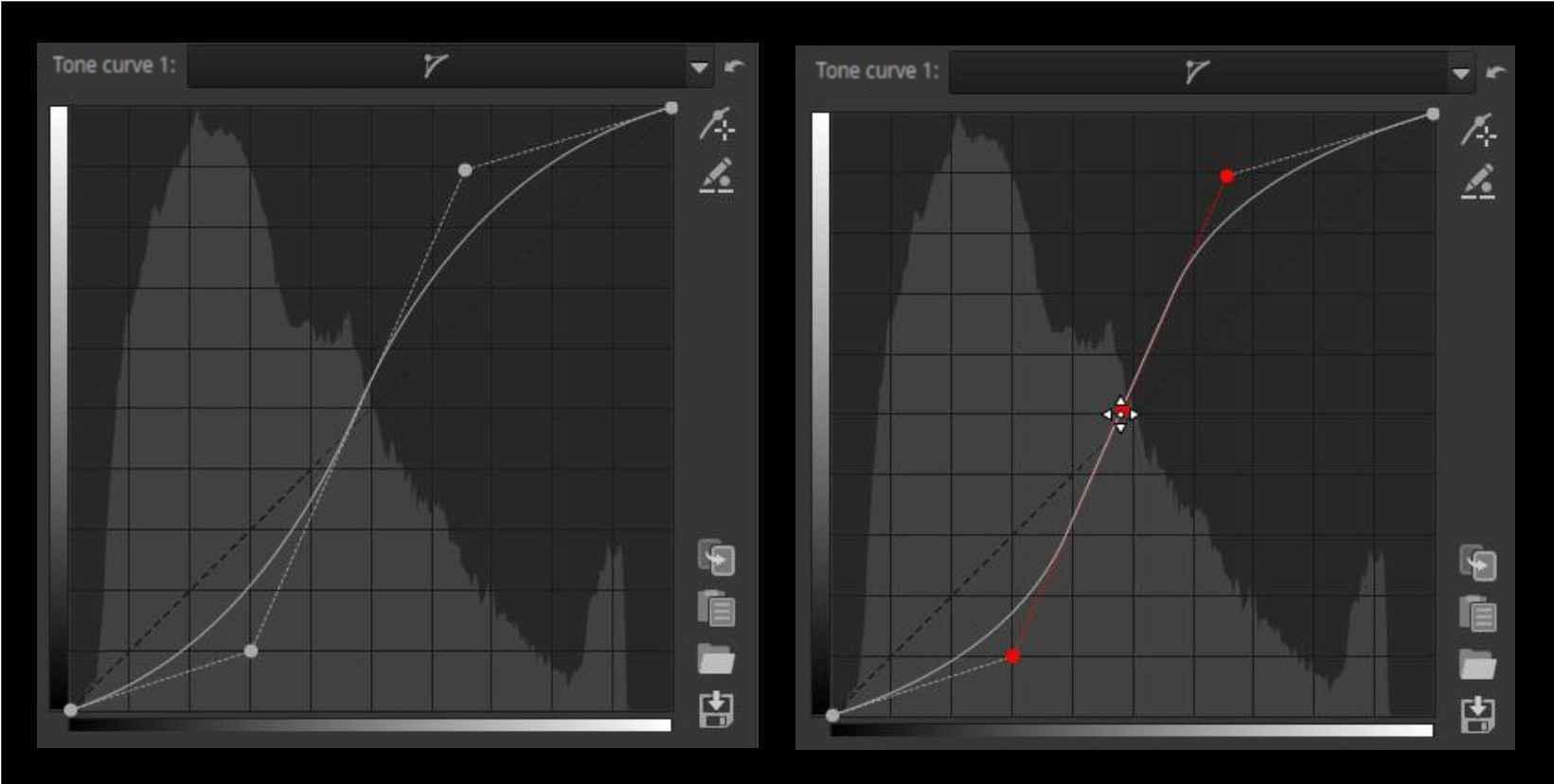

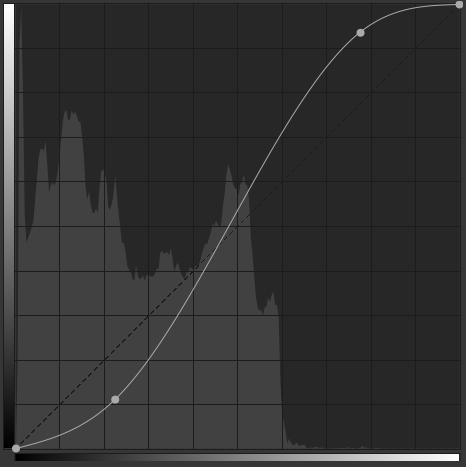

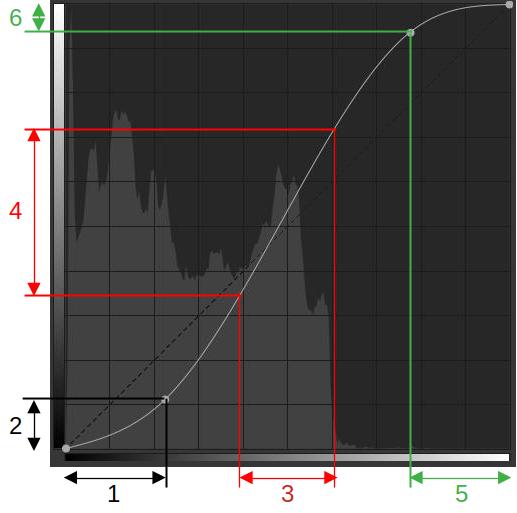

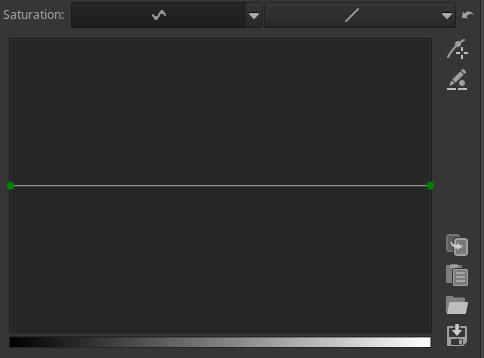

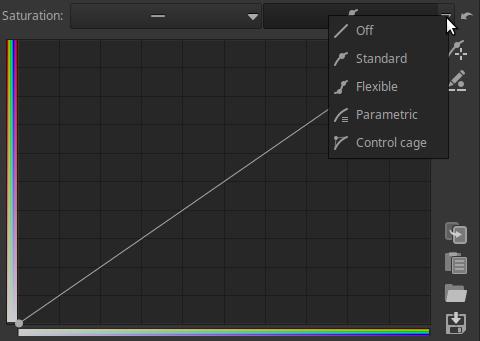

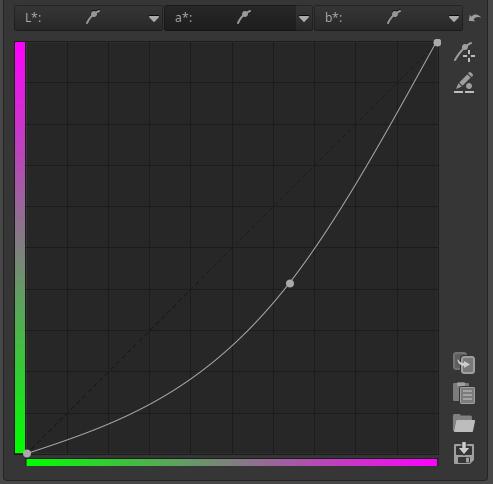

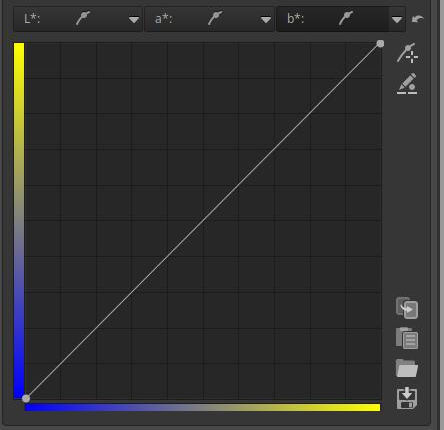

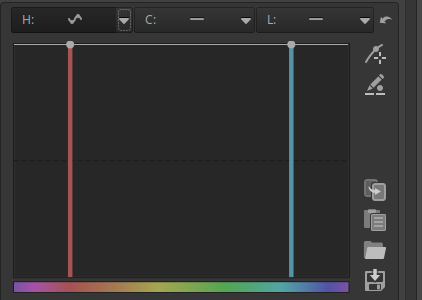

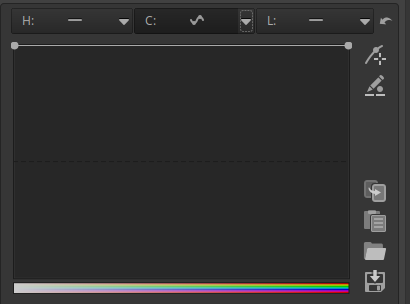

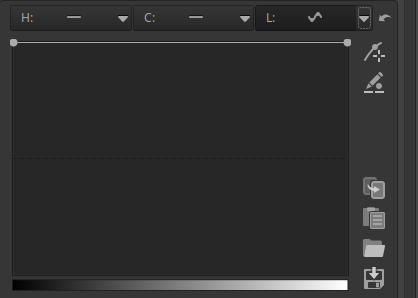

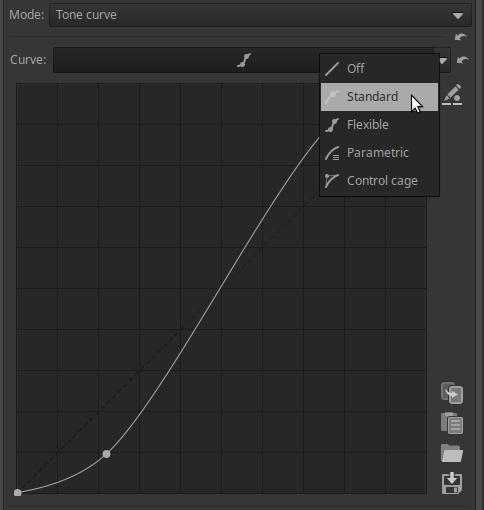

3.14.2.1 Tone curve editor

3.14.2.2 S-curve

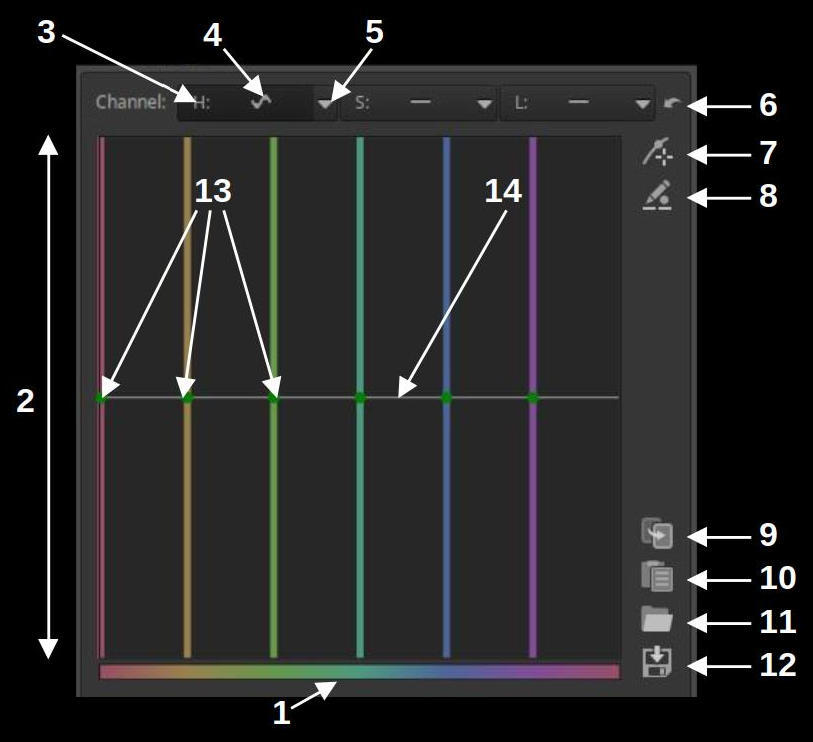

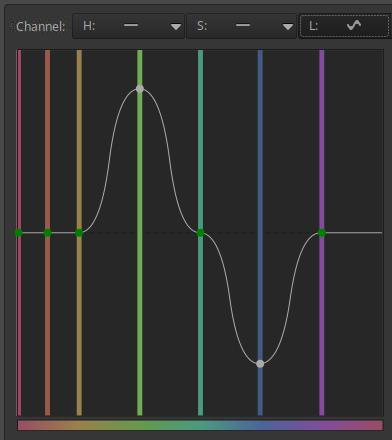

3.14.2.3 Flat curve editor

3.14.2.4 Threshold curve editor

3.15 CTL scripts in ART

3.16 Basic ART workflow

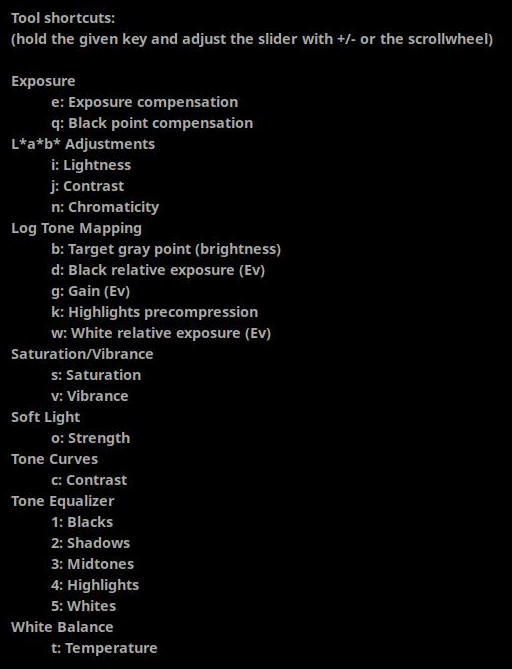

3.17 Editor shortcuts

4. ART editing tools by tool group

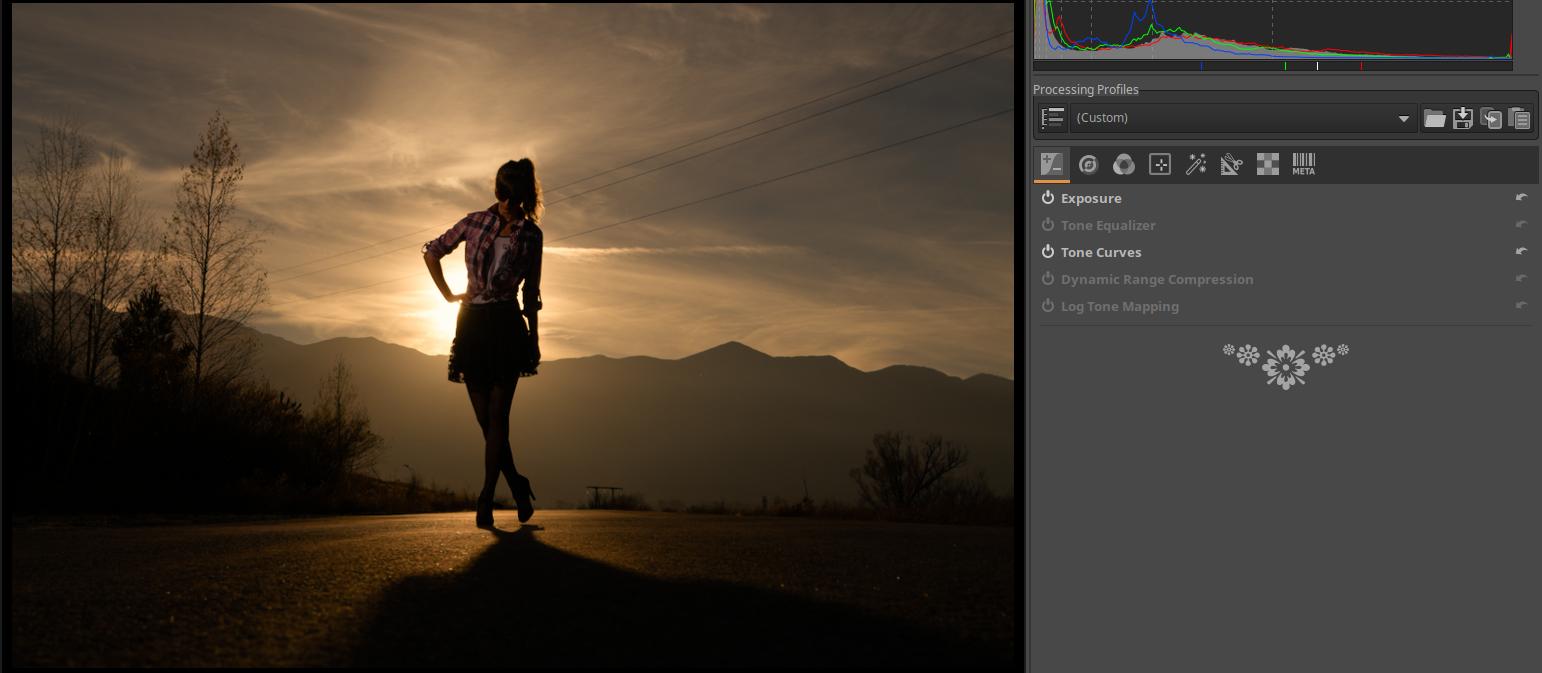

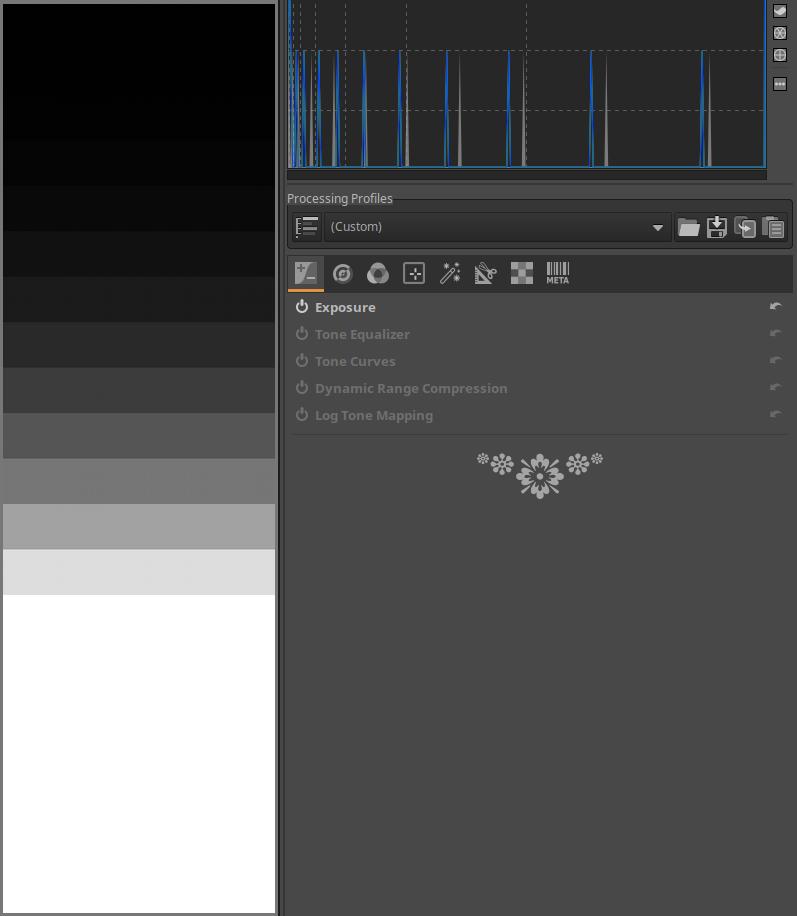

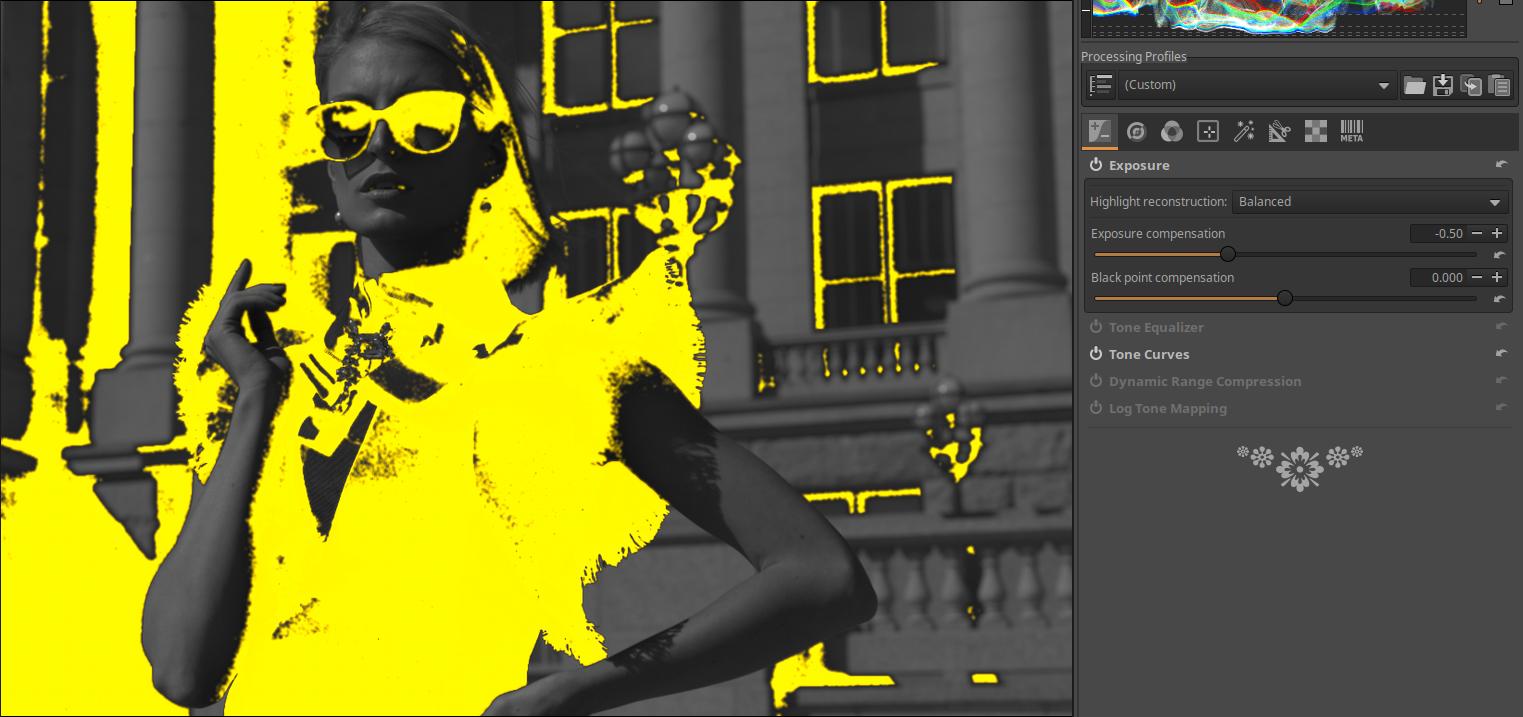

4.1 Exposure group

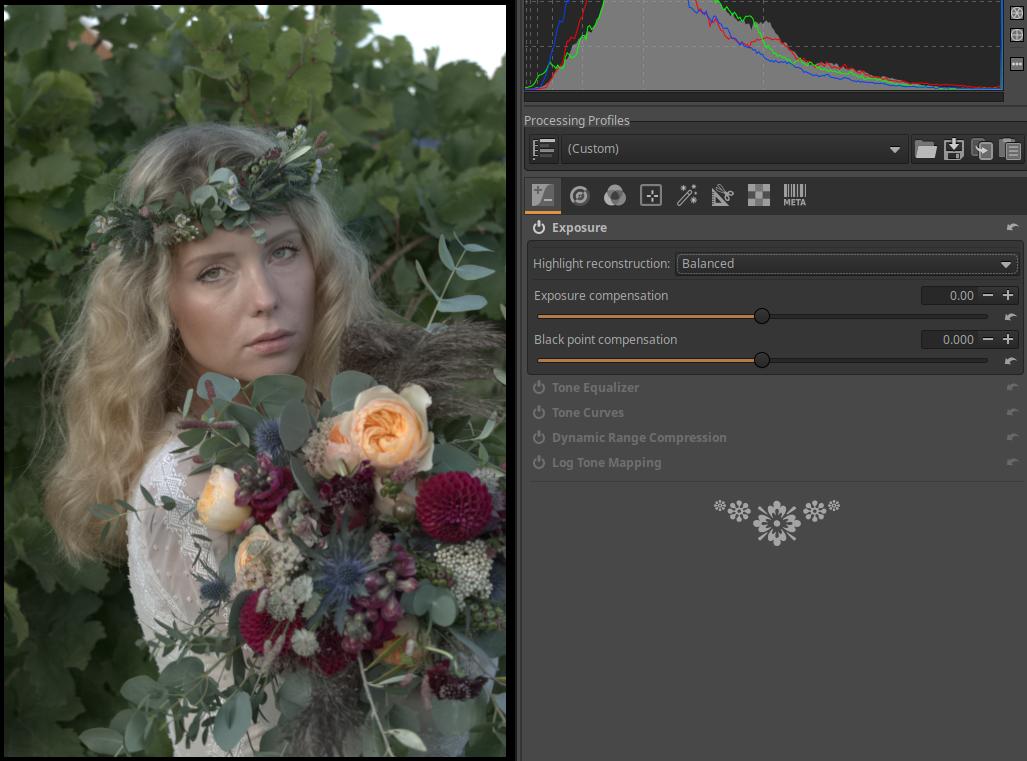

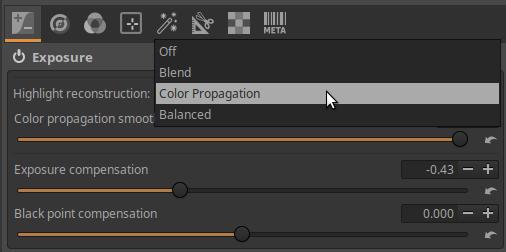

4.1.1 Exposure

4.1.1.1 Covering burned area with Color Propagation

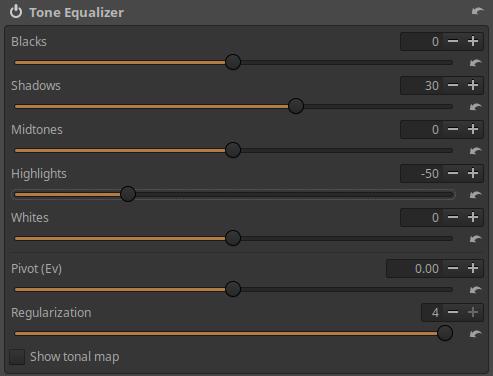

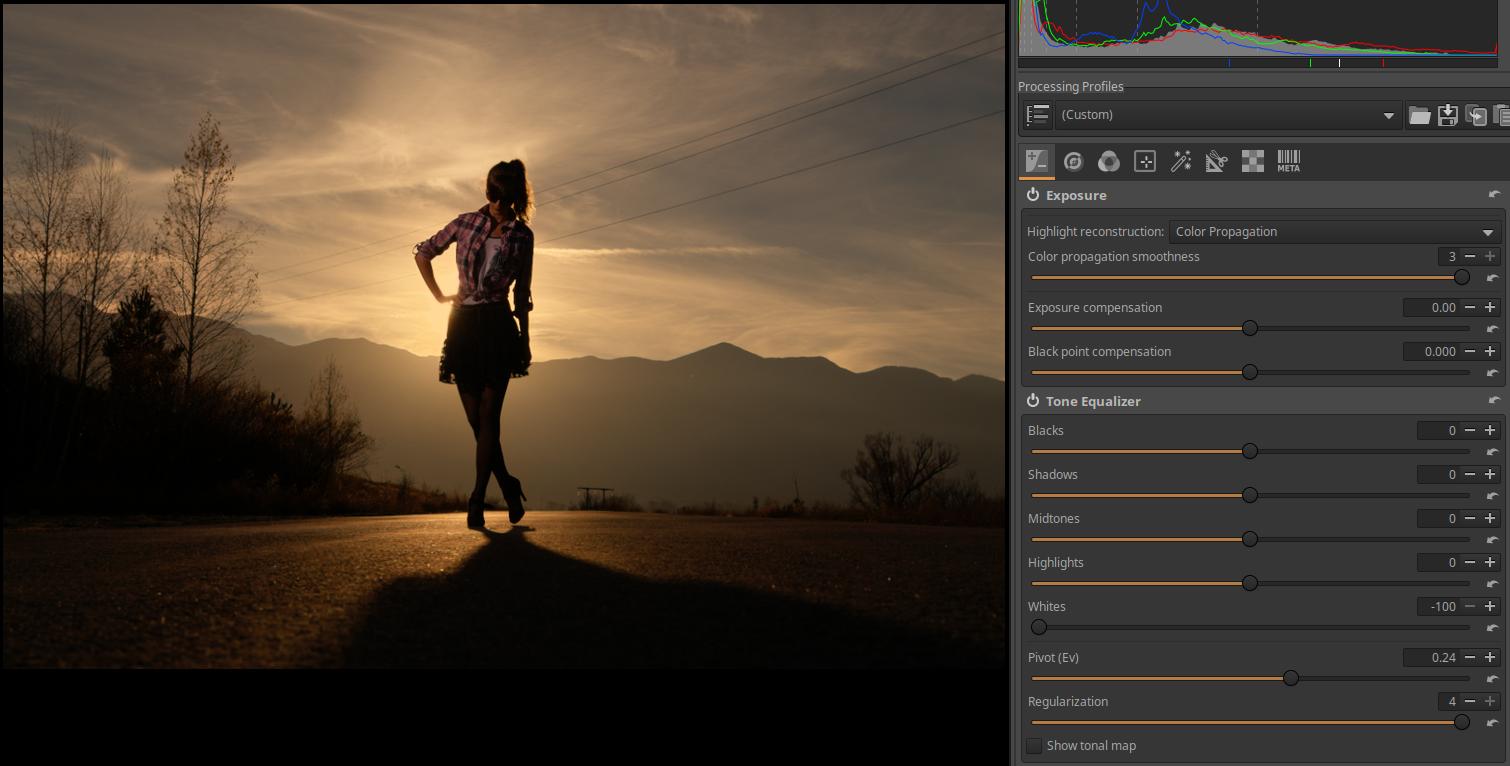

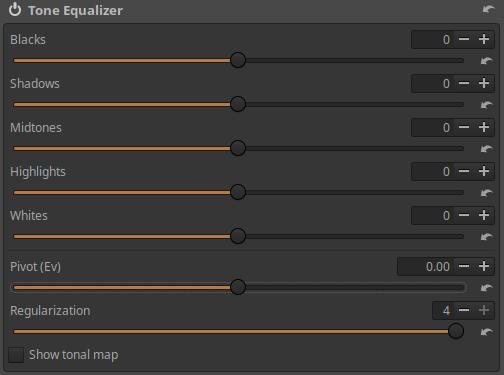

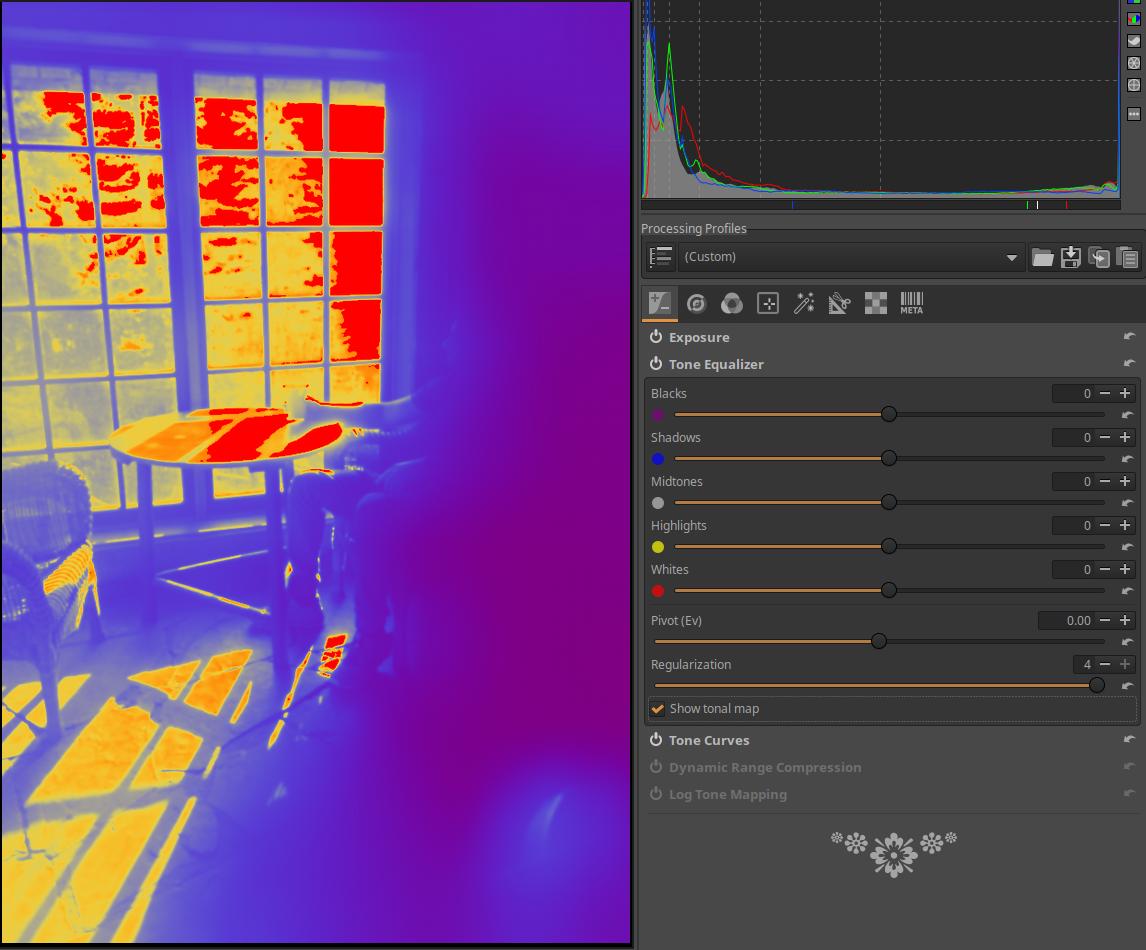

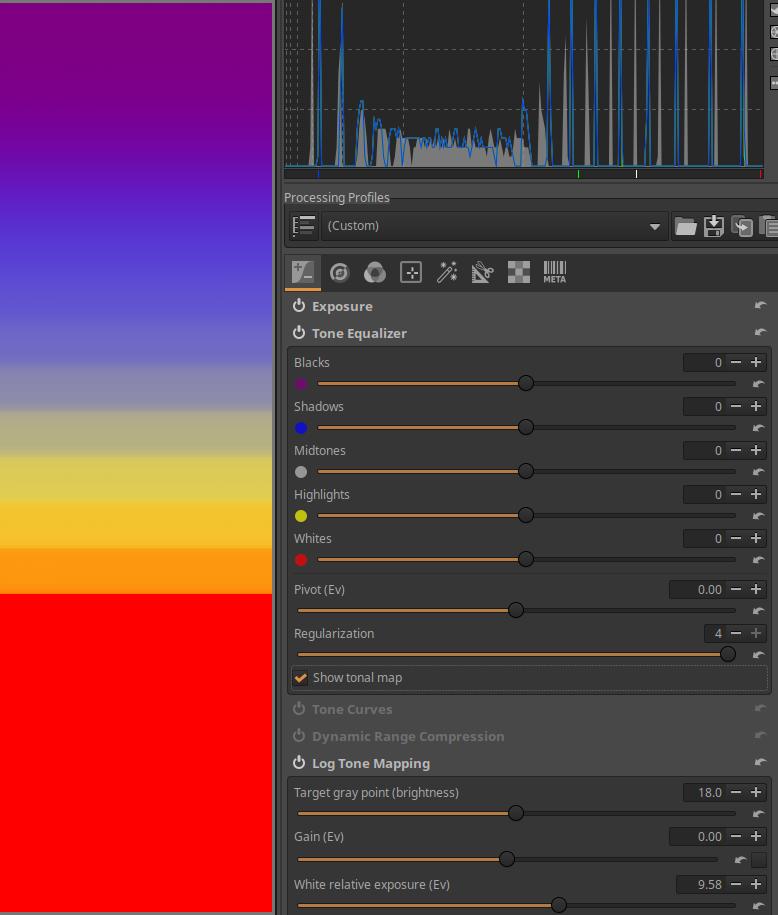

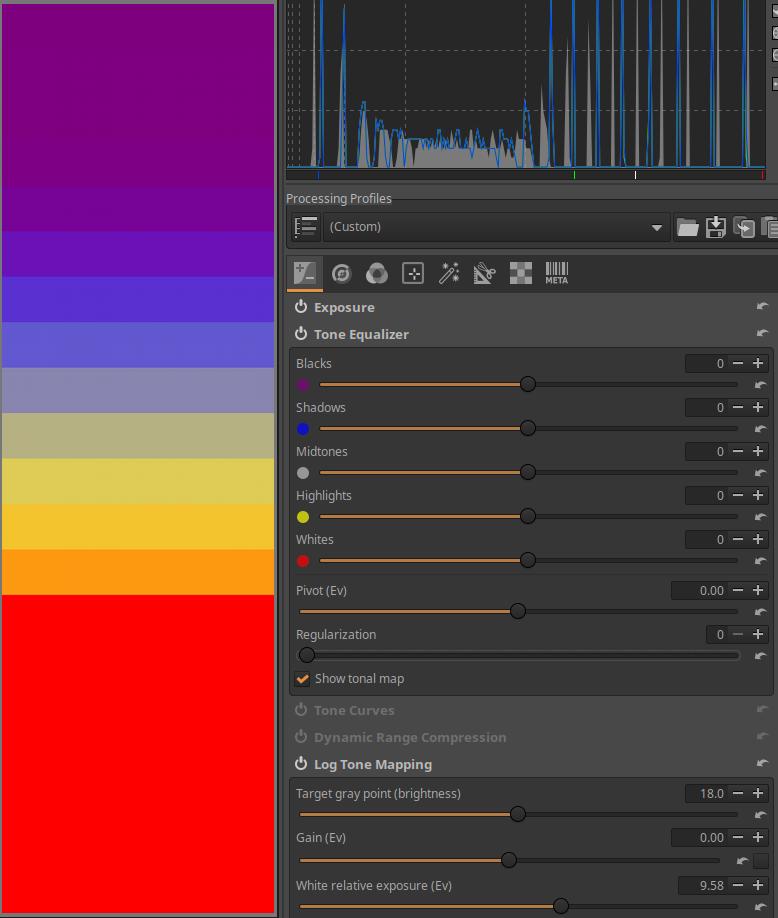

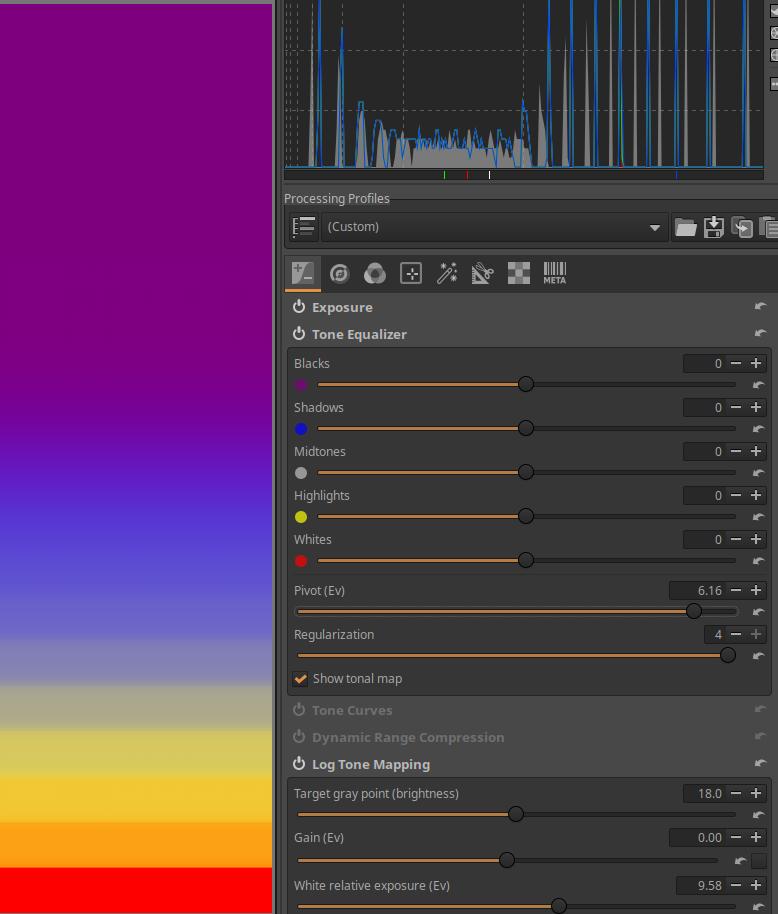

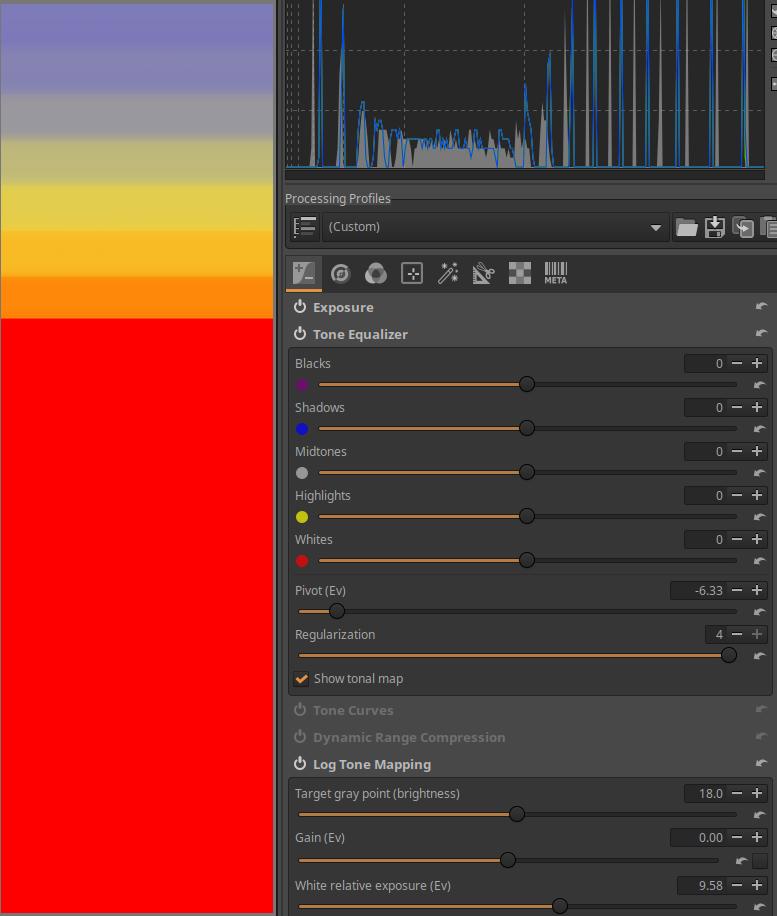

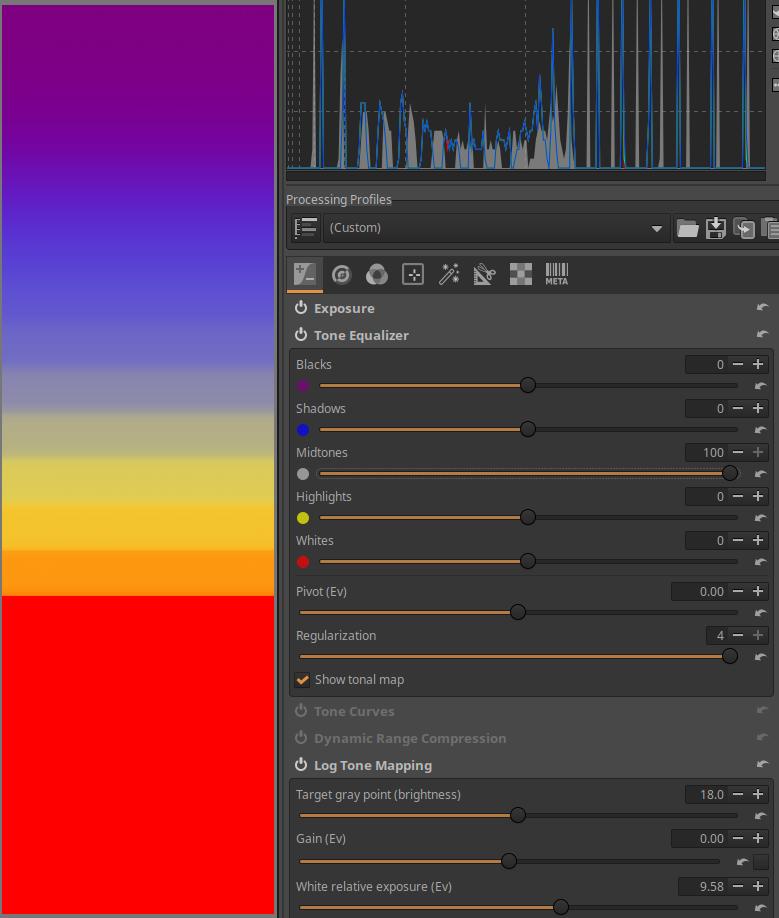

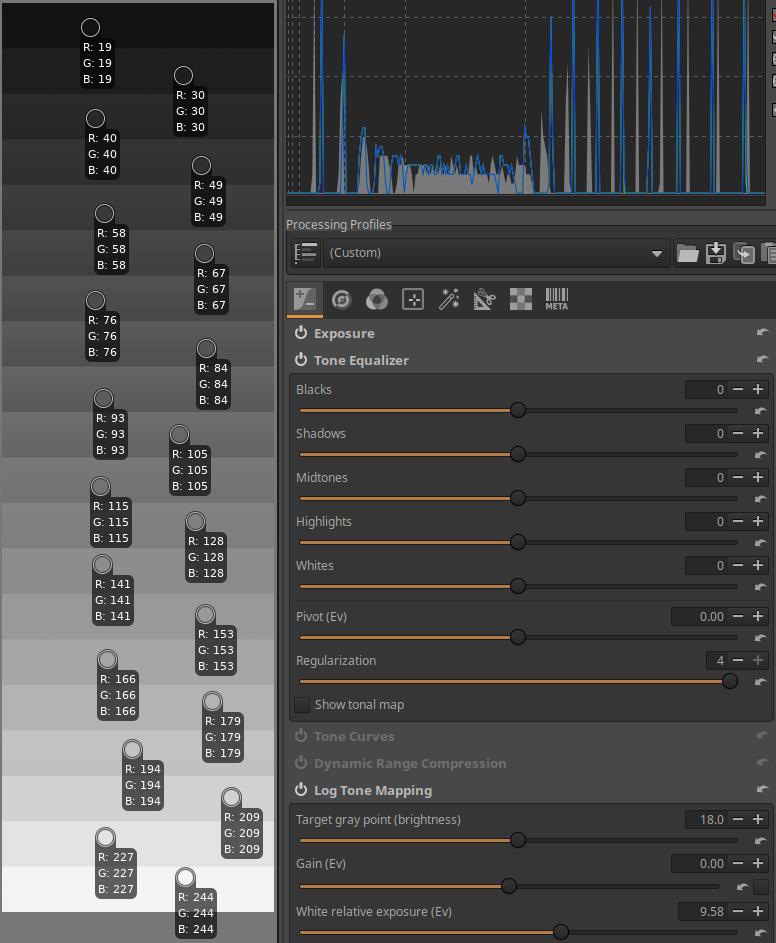

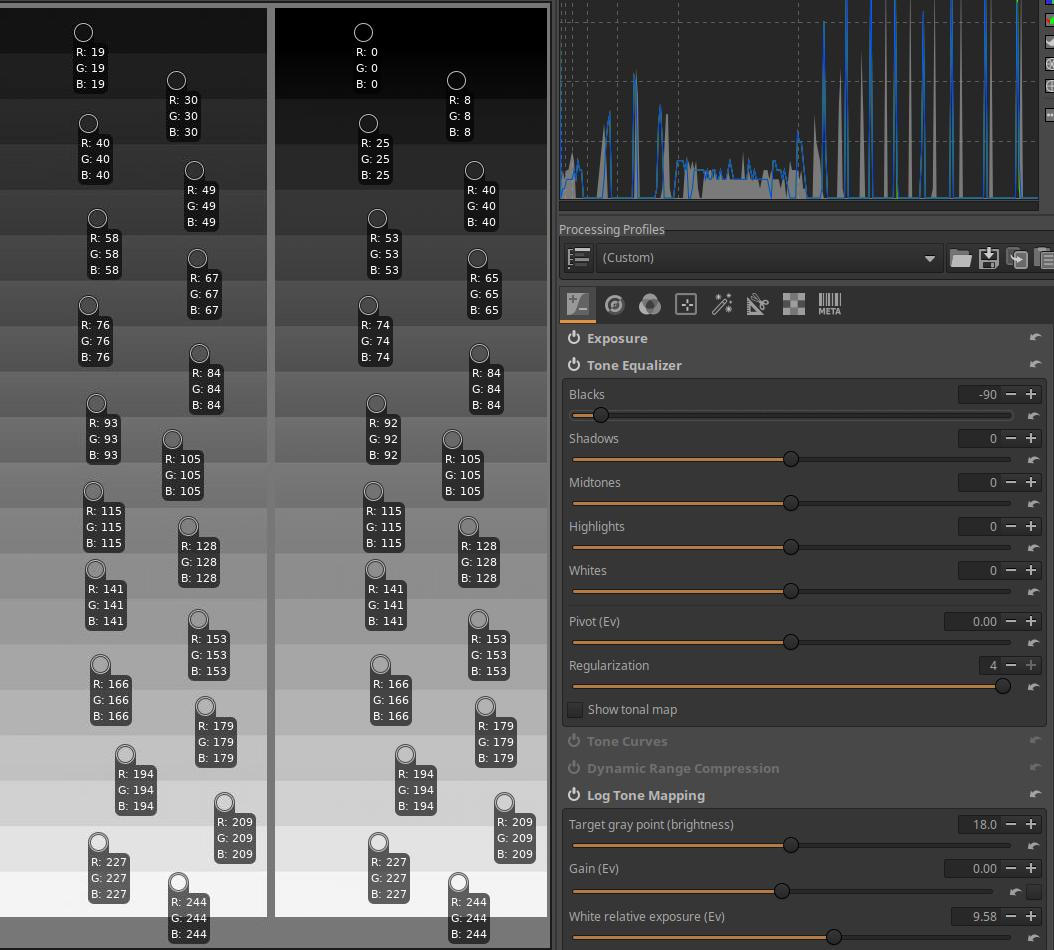

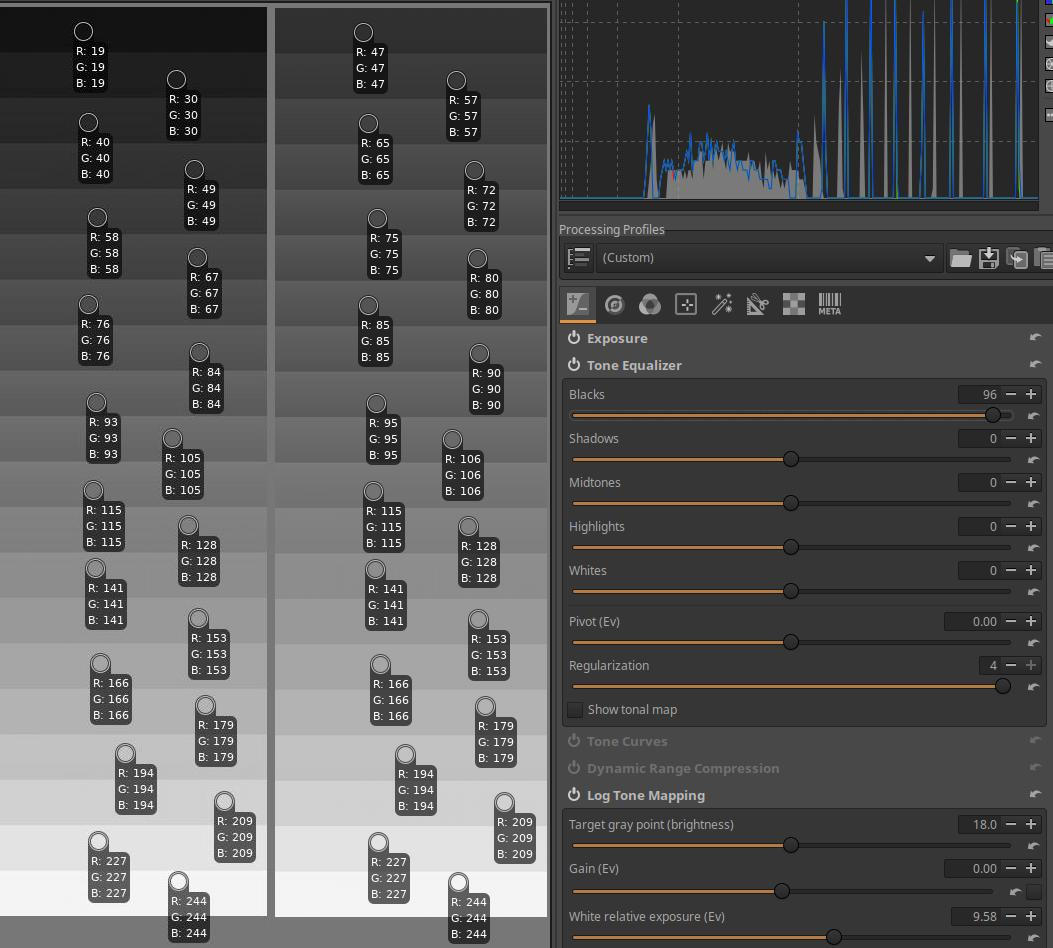

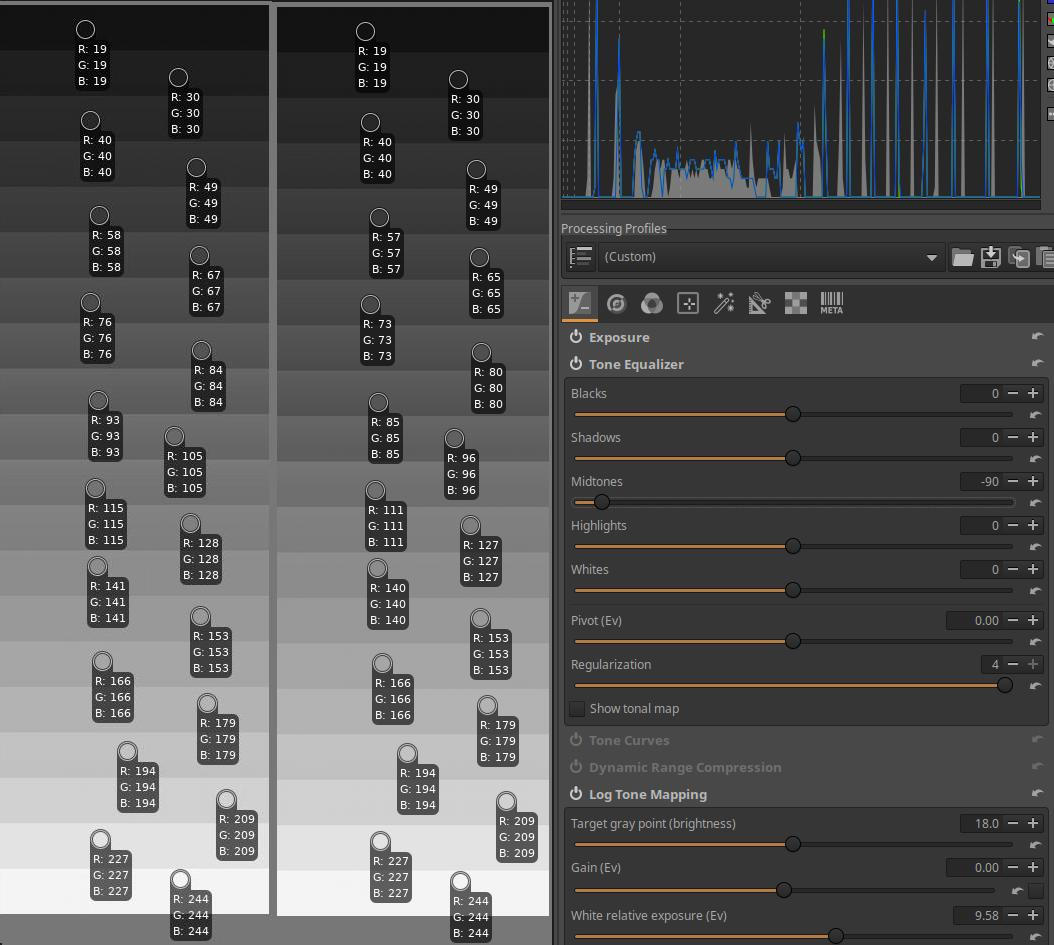

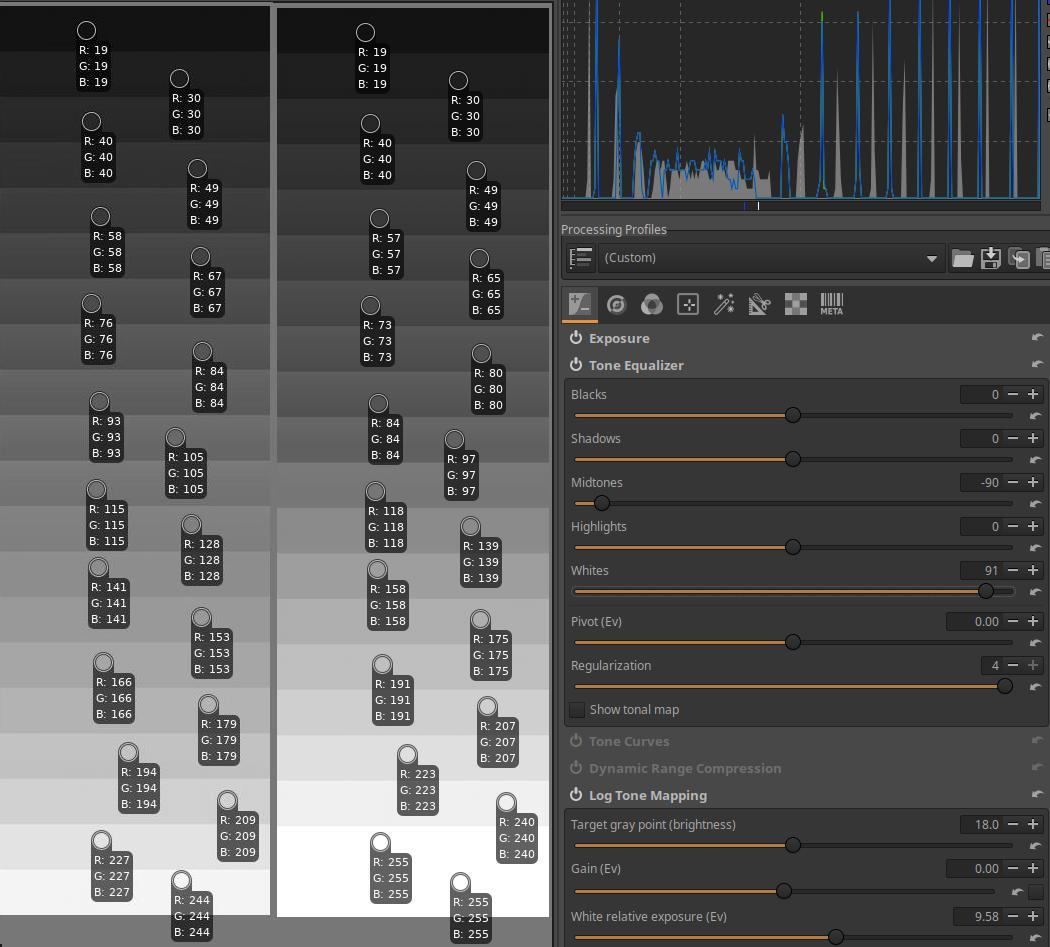

4.1.2 Tone Equalizer

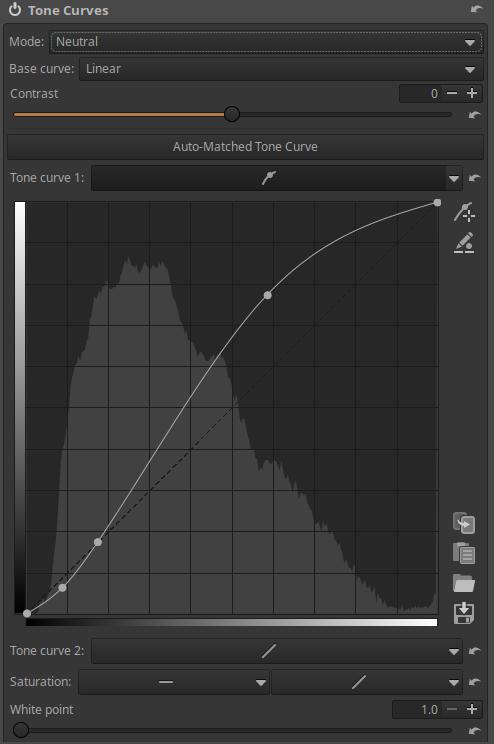

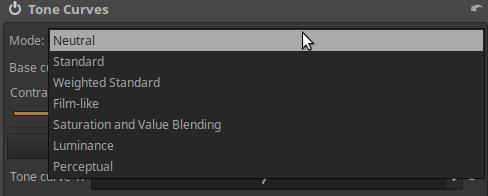

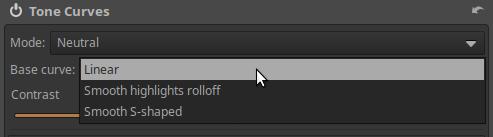

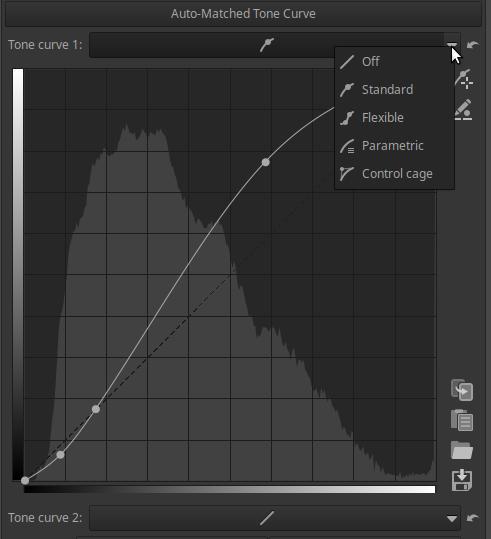

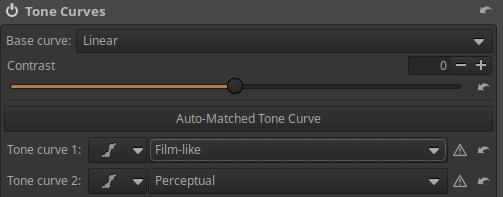

4.1.3 Tone Curves

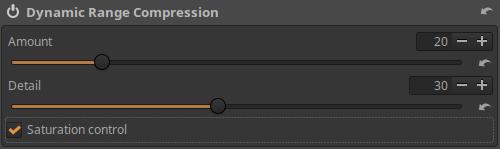

4.1.4 Dynamic Range Compression

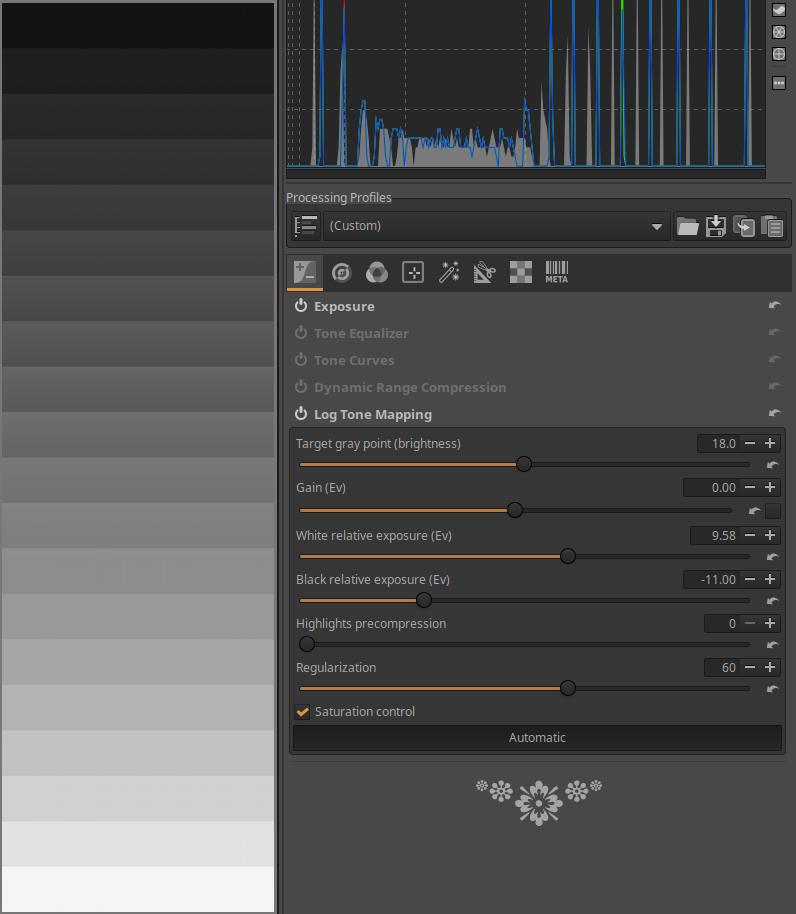

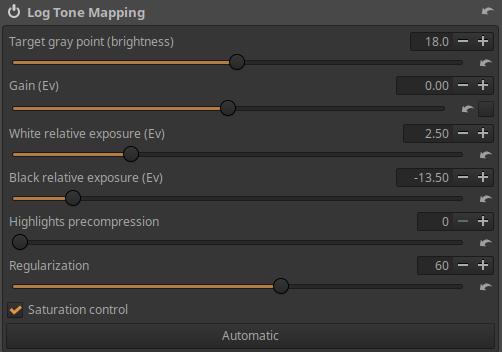

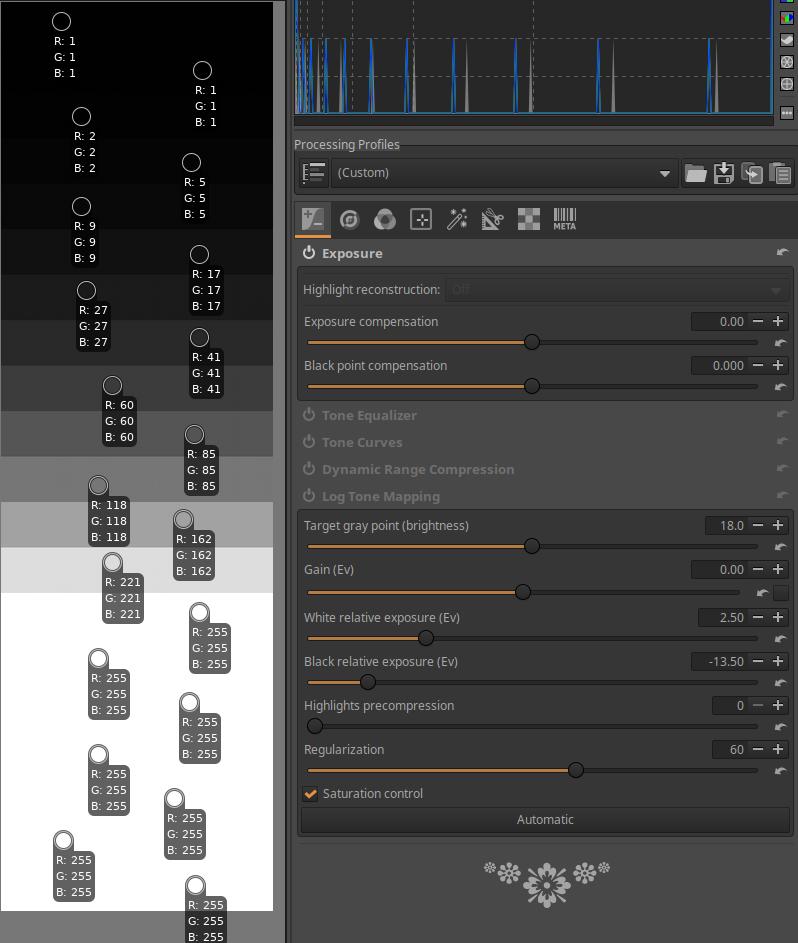

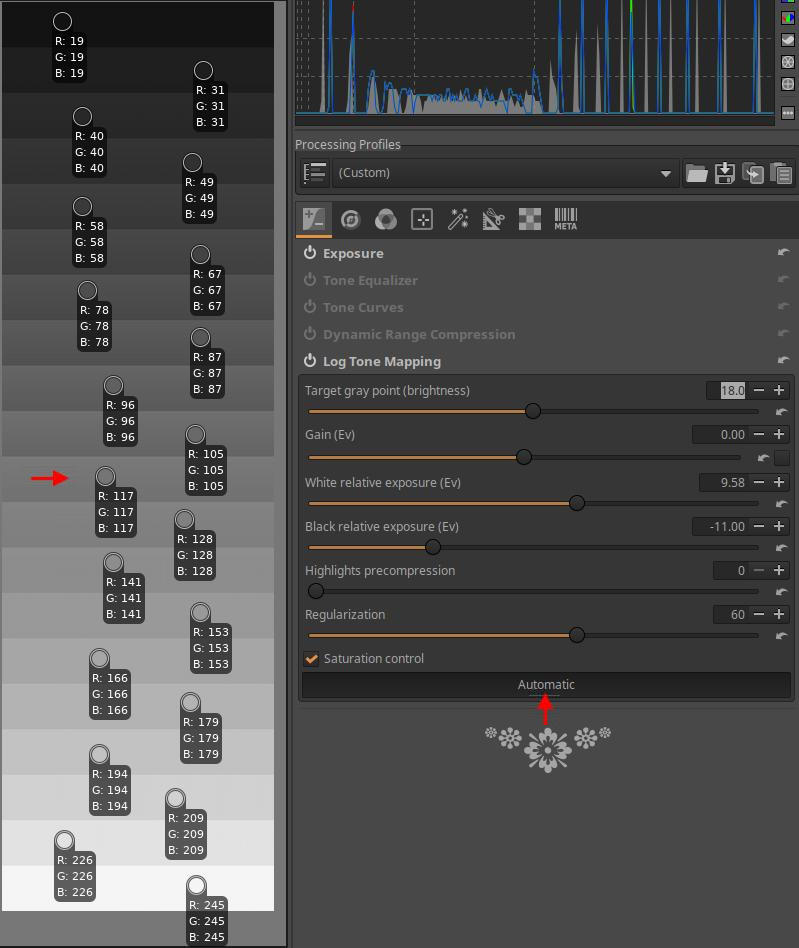

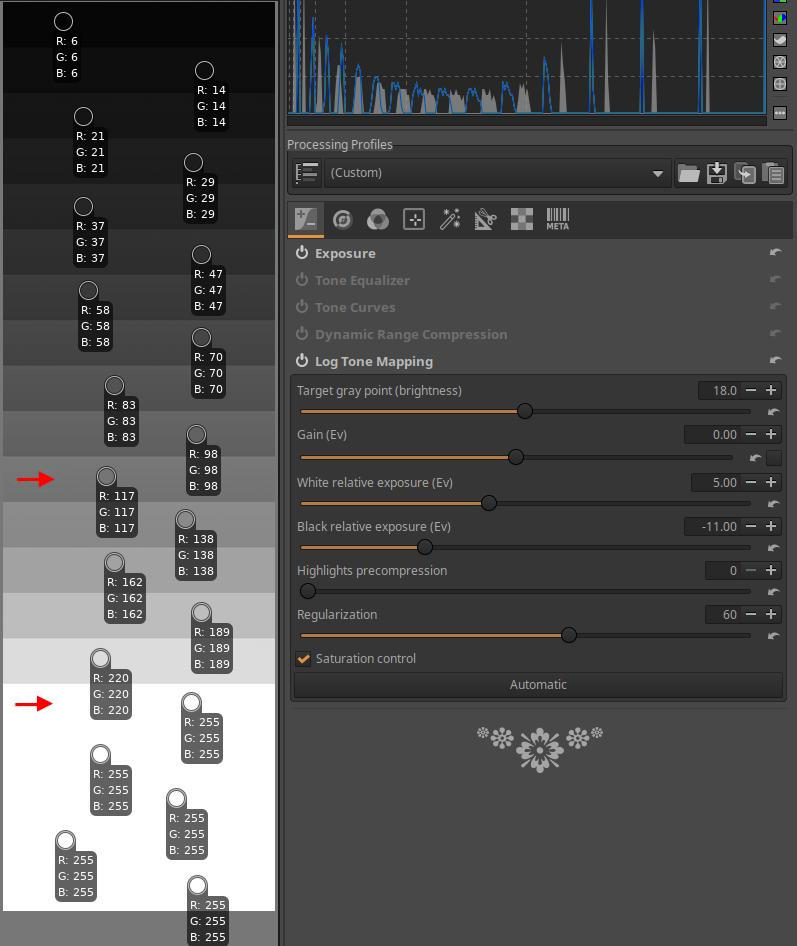

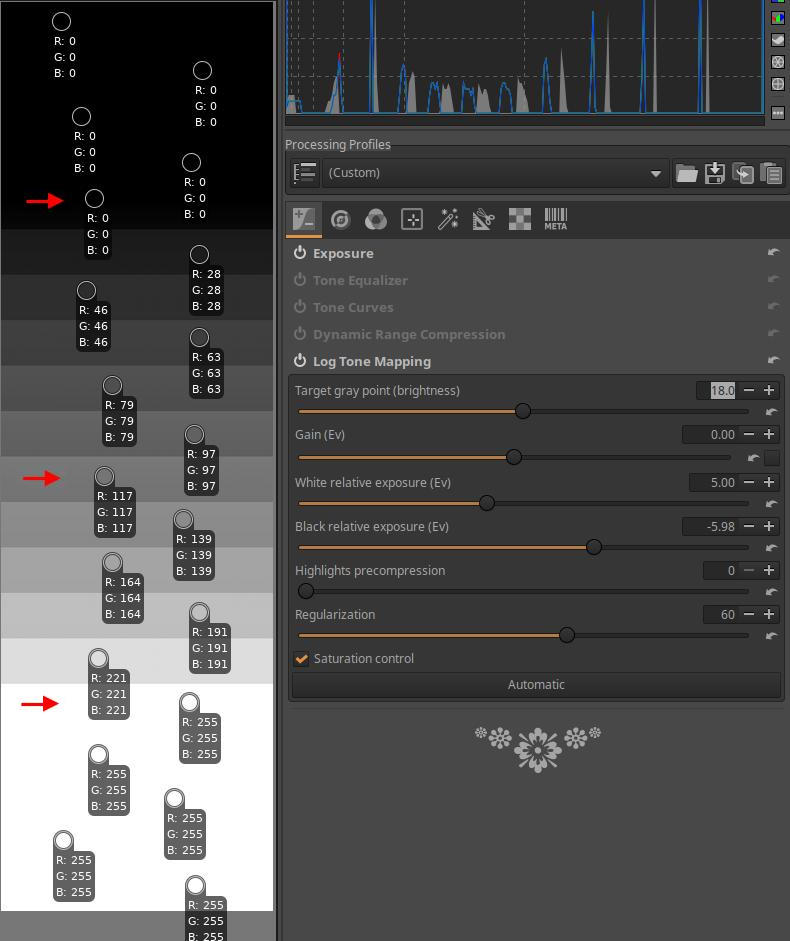

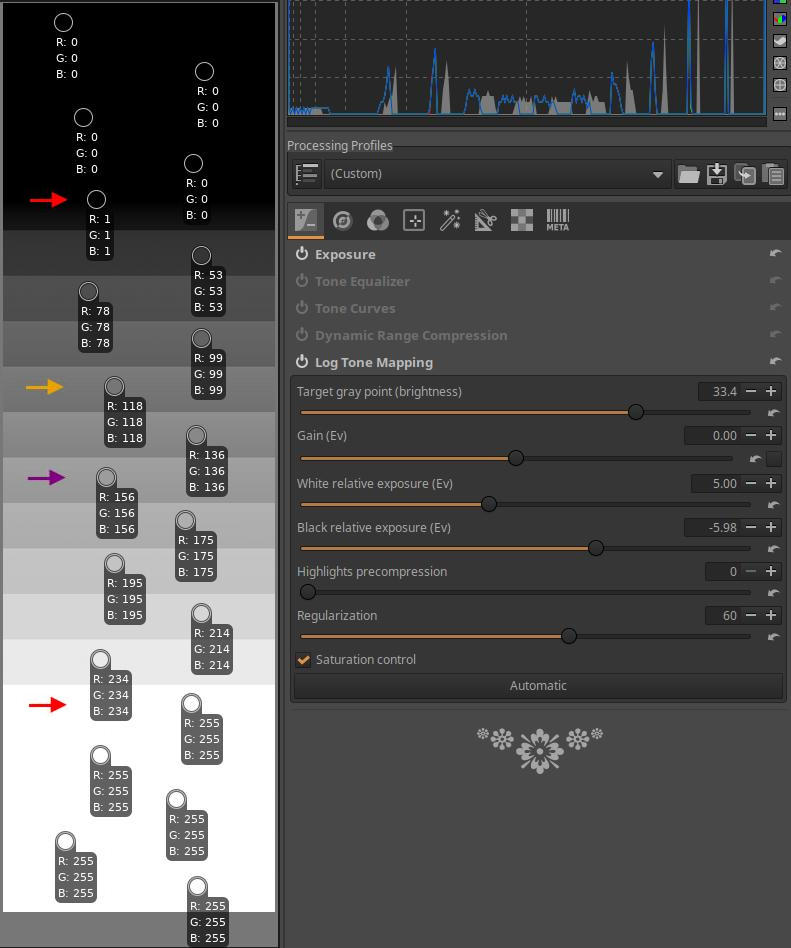

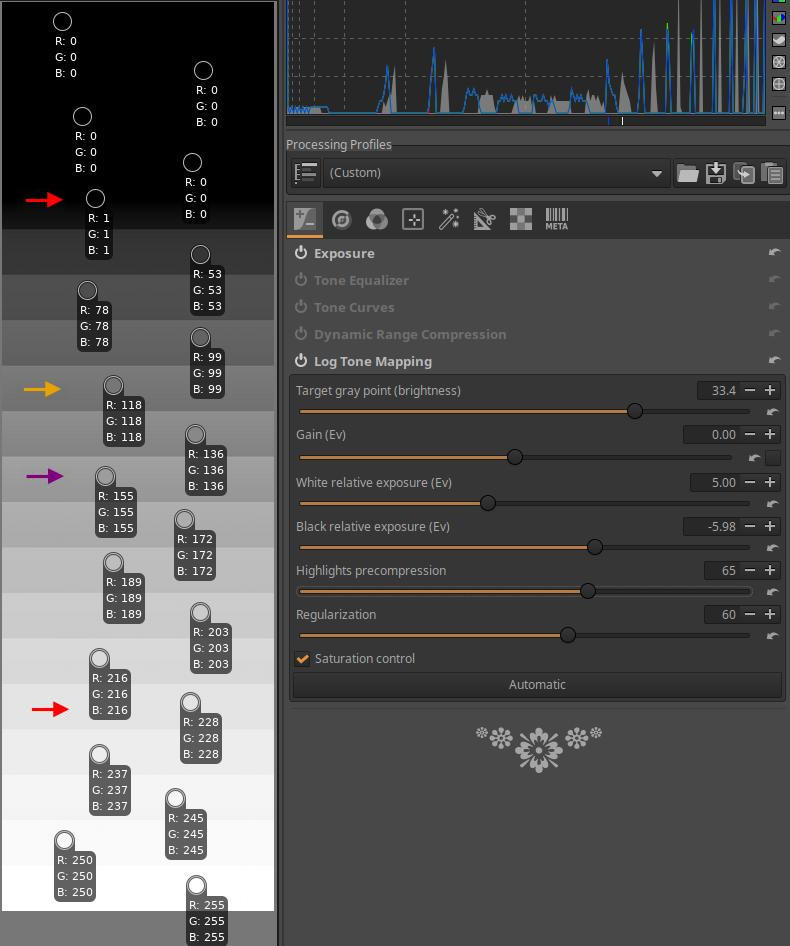

4.1.5 Log Tone Mapping

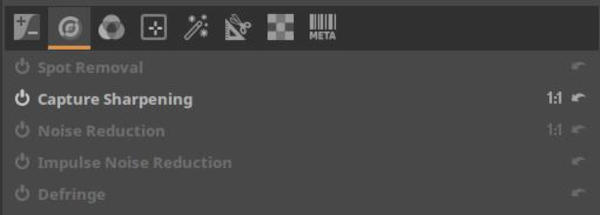

4.2 Details group

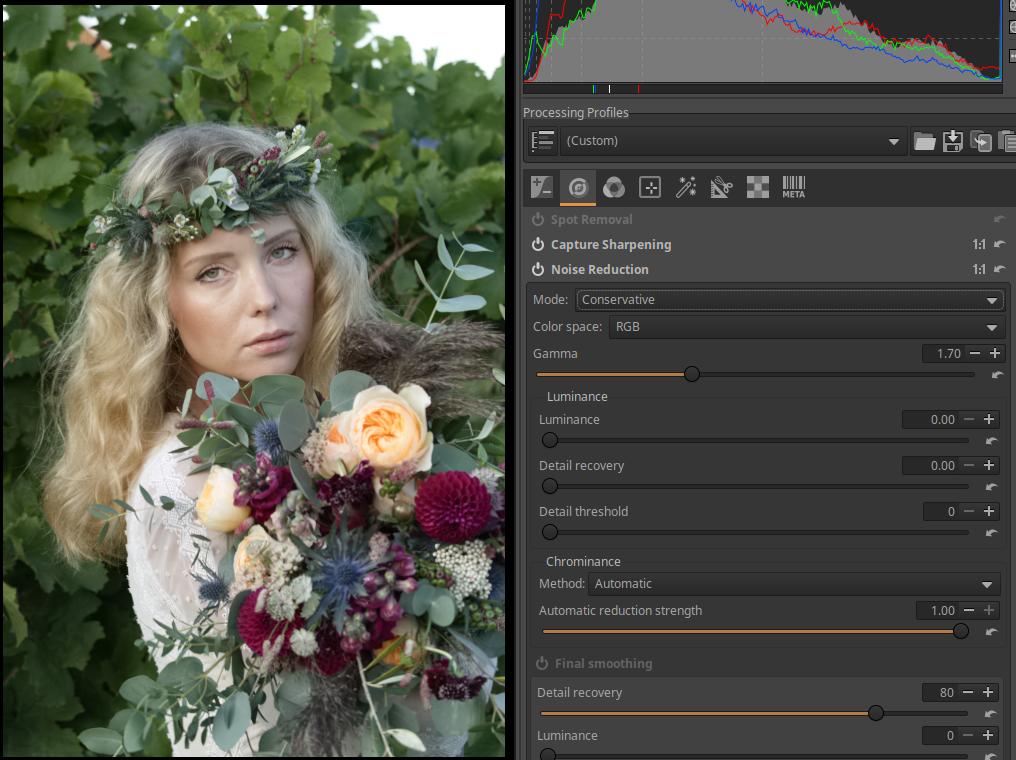

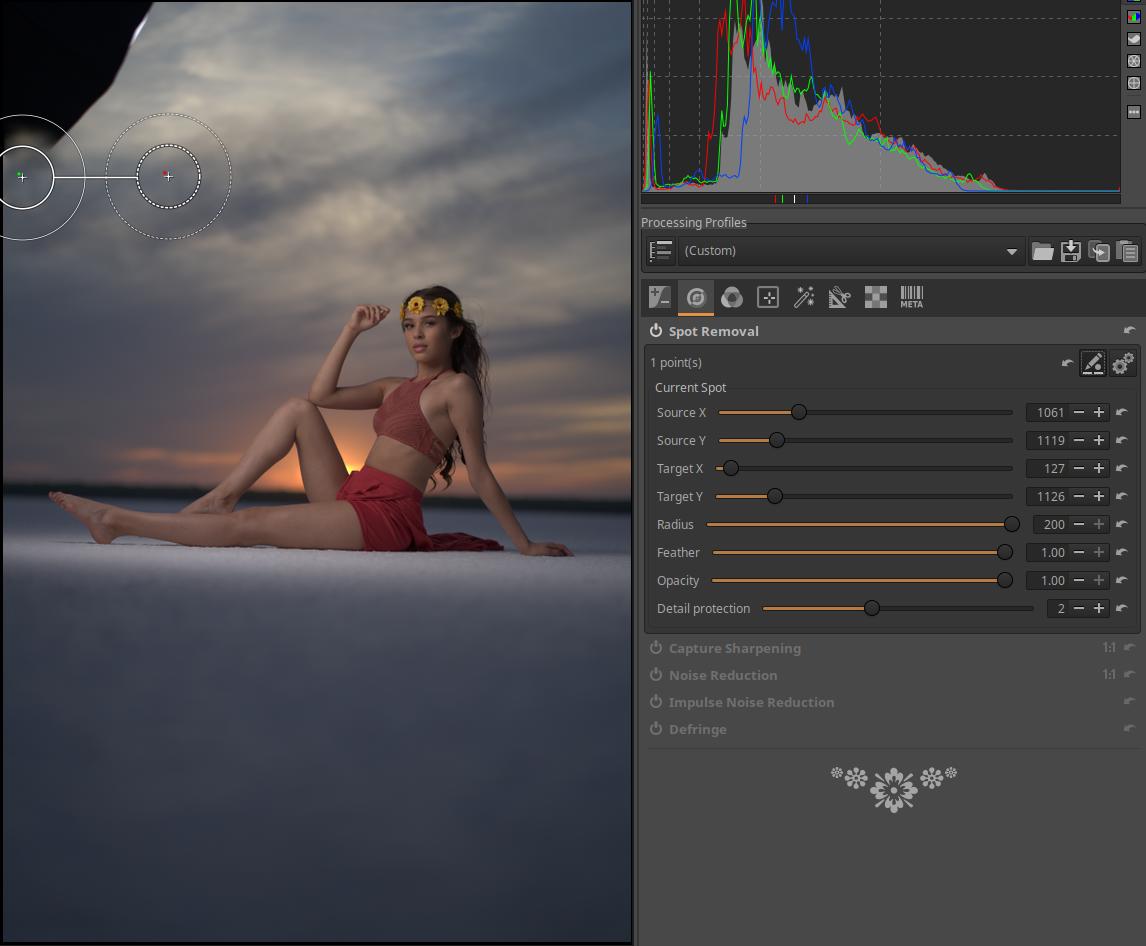

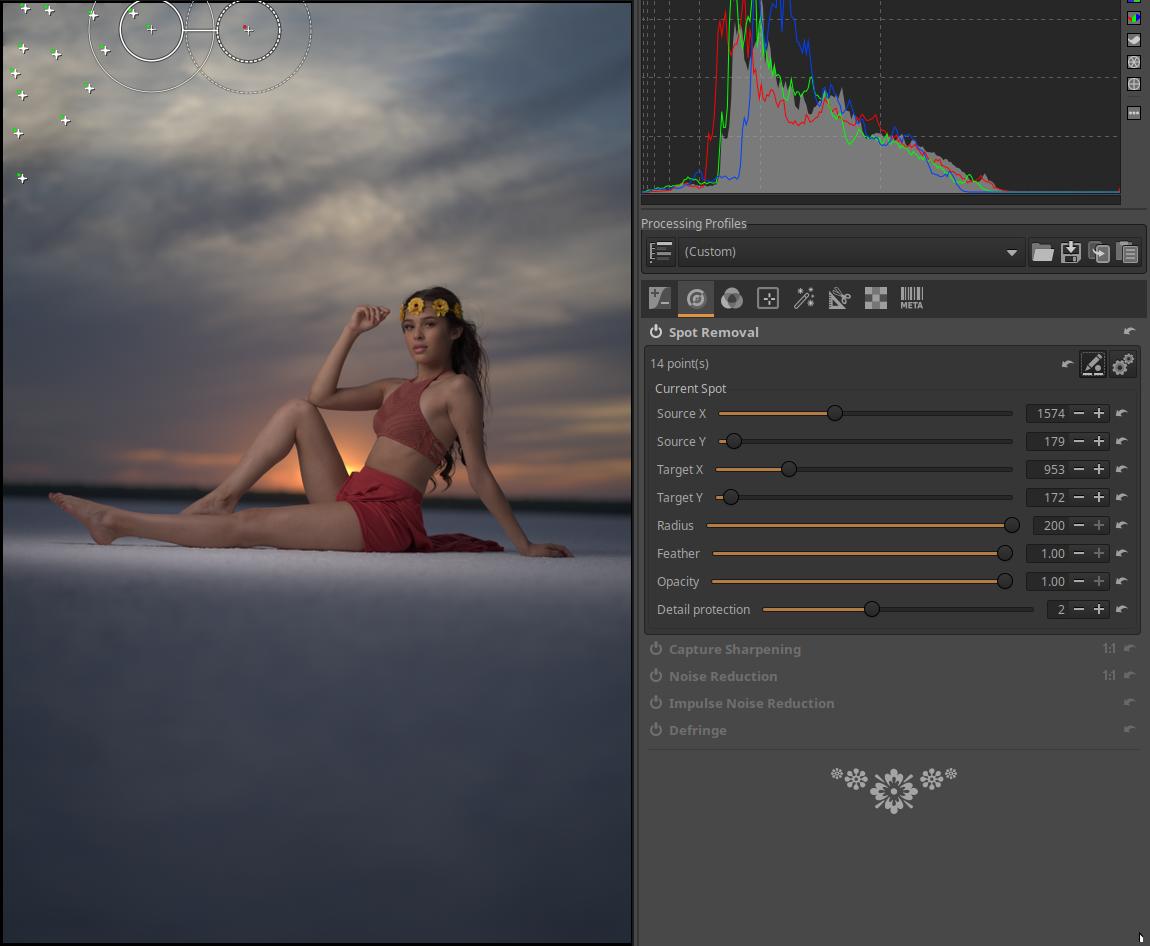

4.2.1 Spot Removal

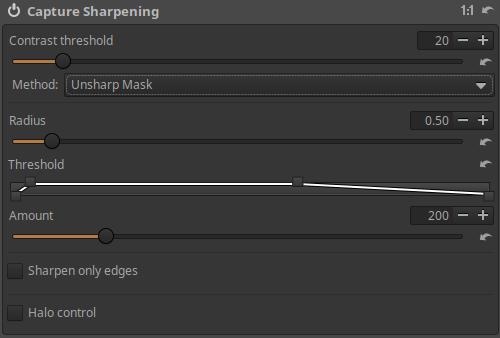

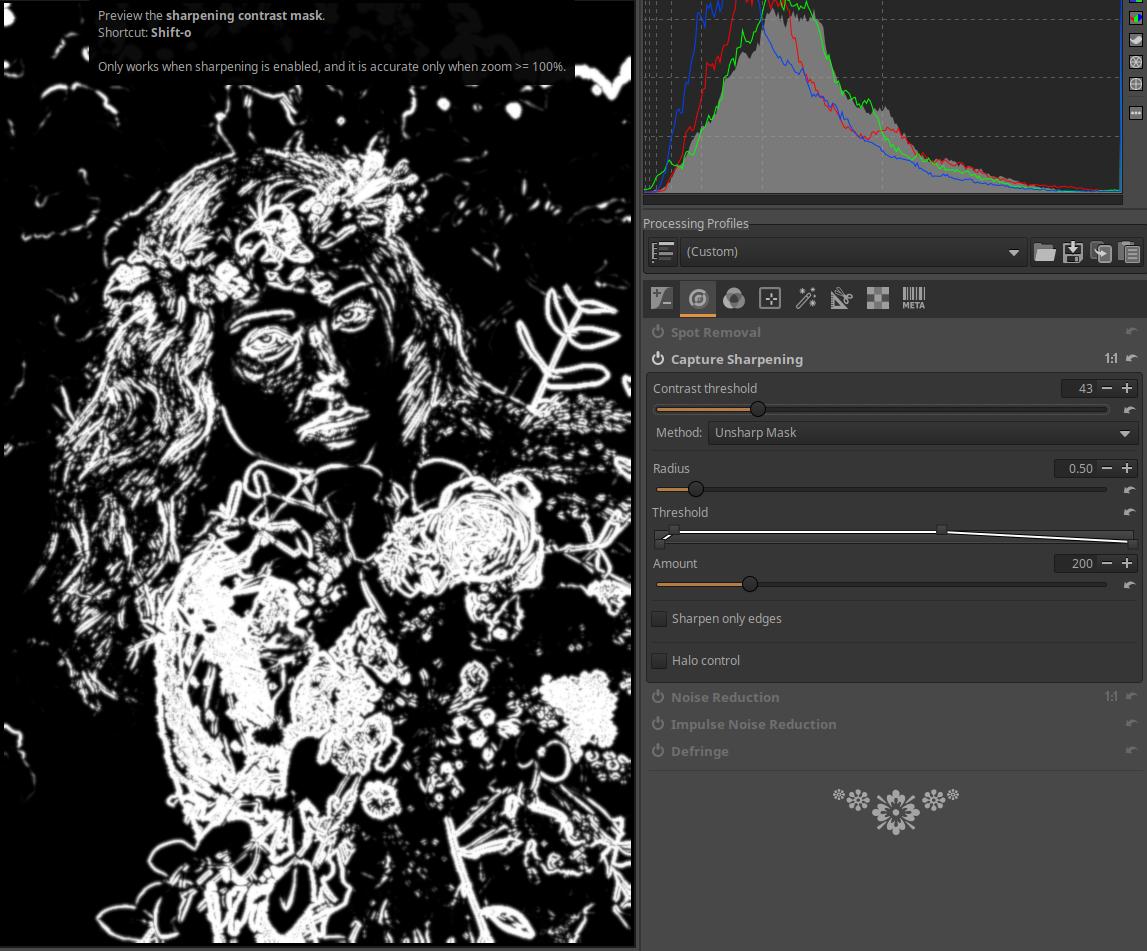

4.2.2 Capture Sharpening

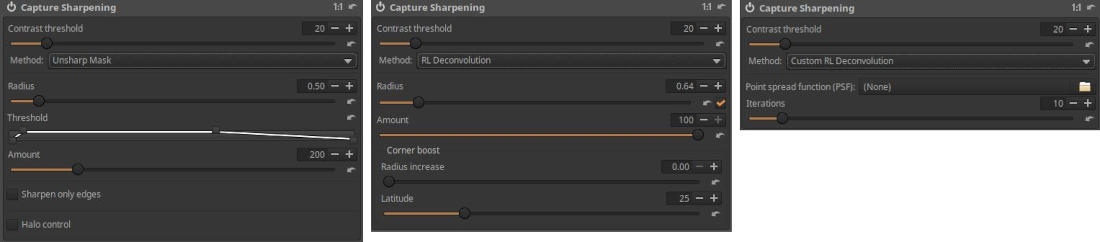

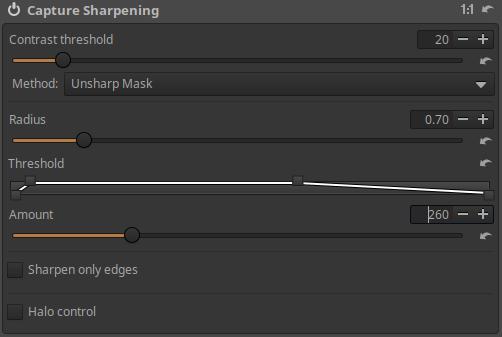

4.2.2.1 Unsharp Mask

4.2.2.2 RL Deconvolution

4.2.2.3 Custom RL Deconvolution

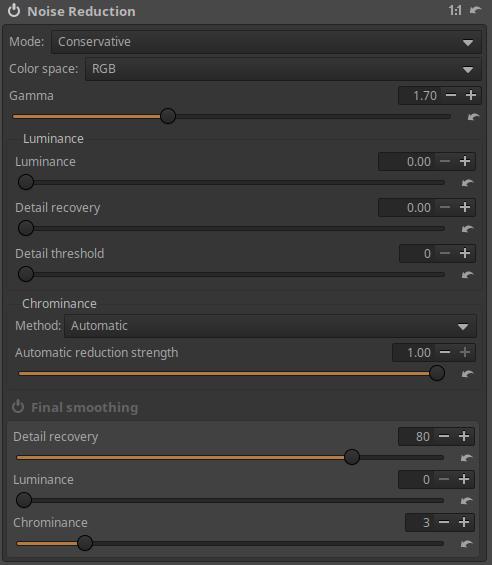

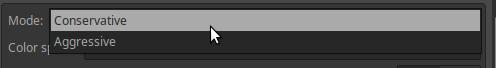

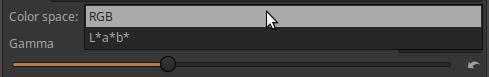

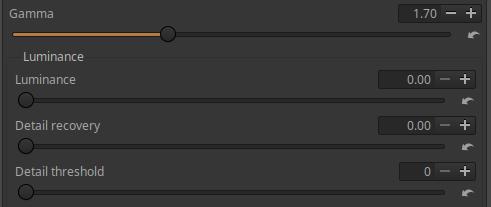

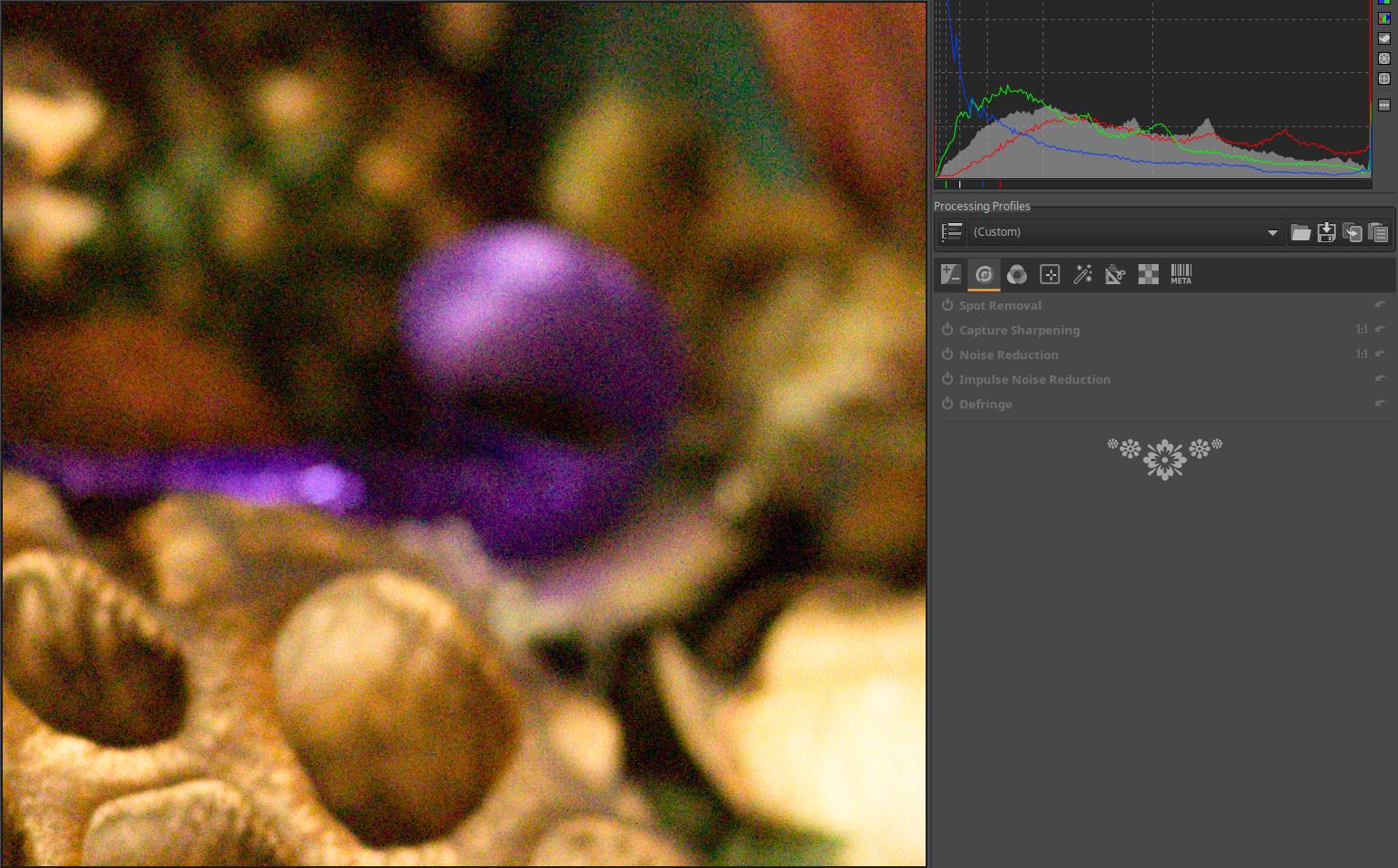

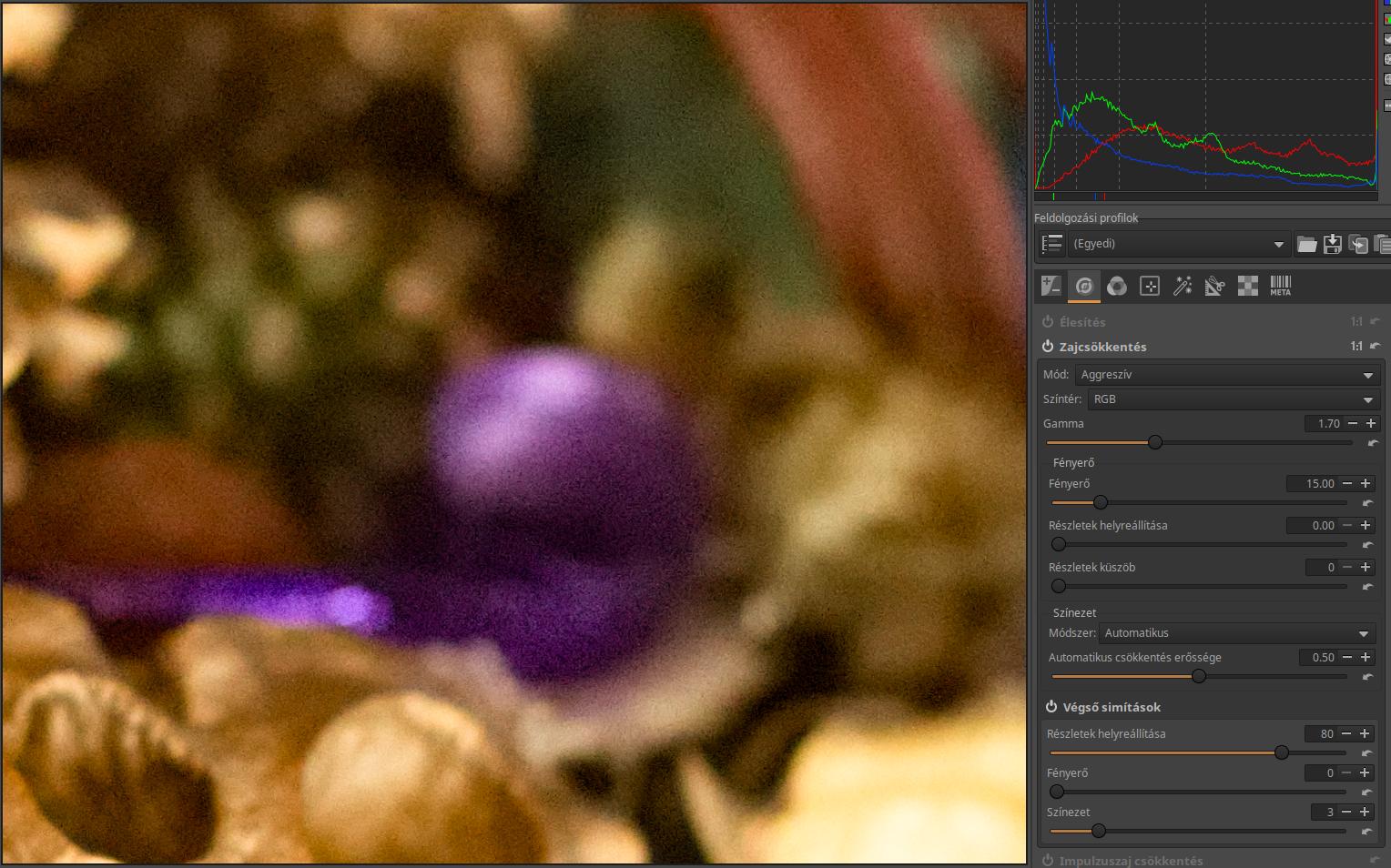

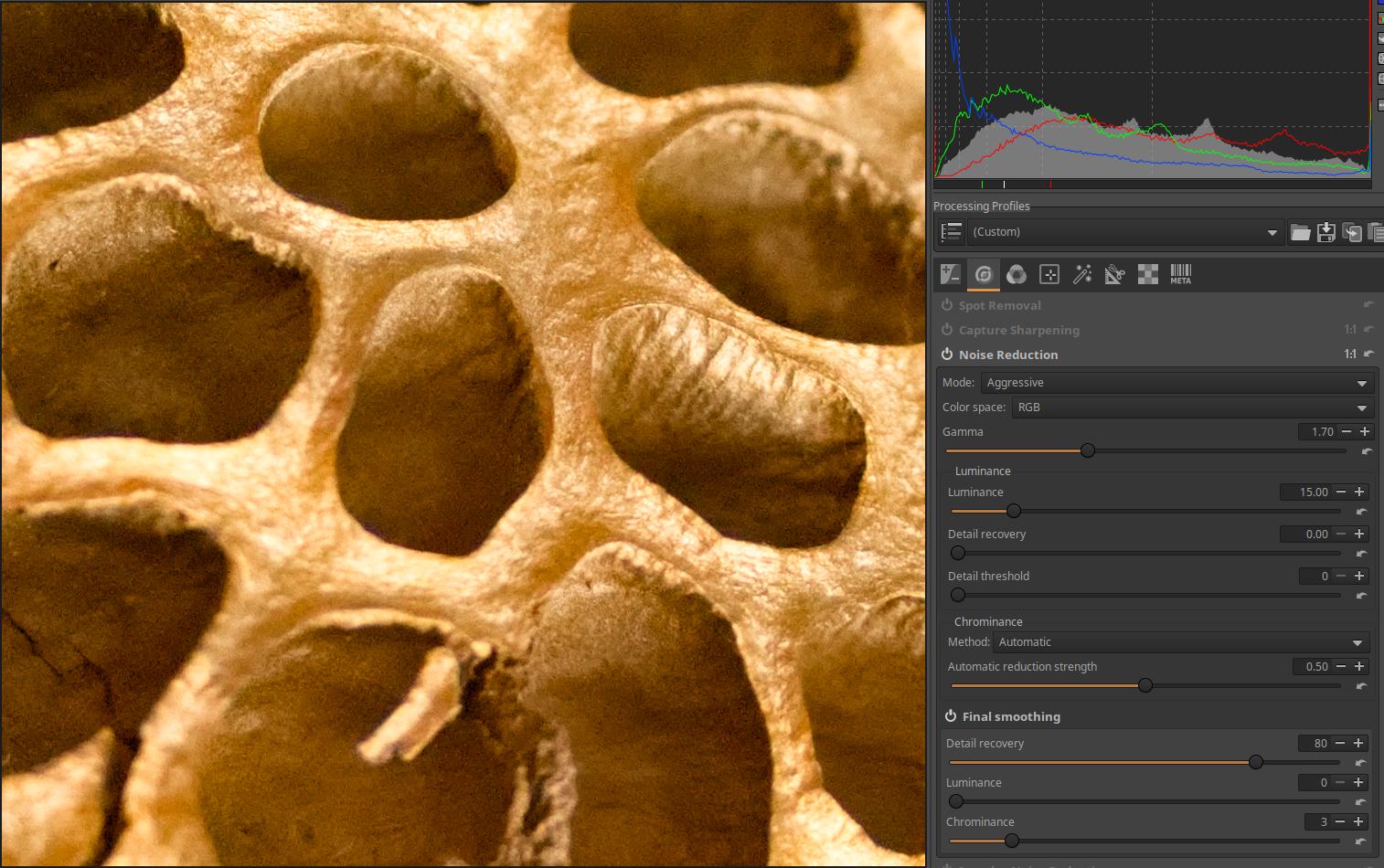

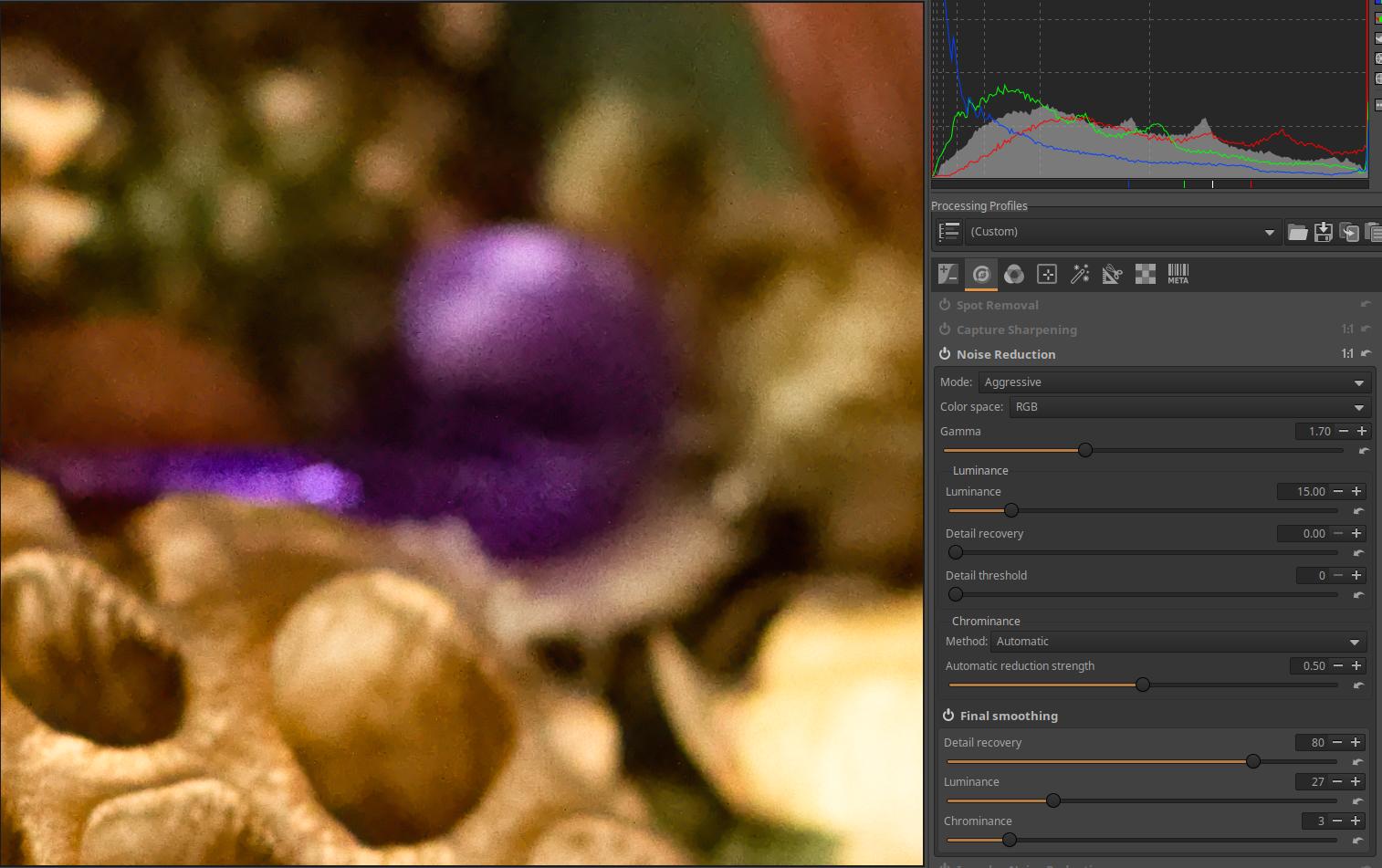

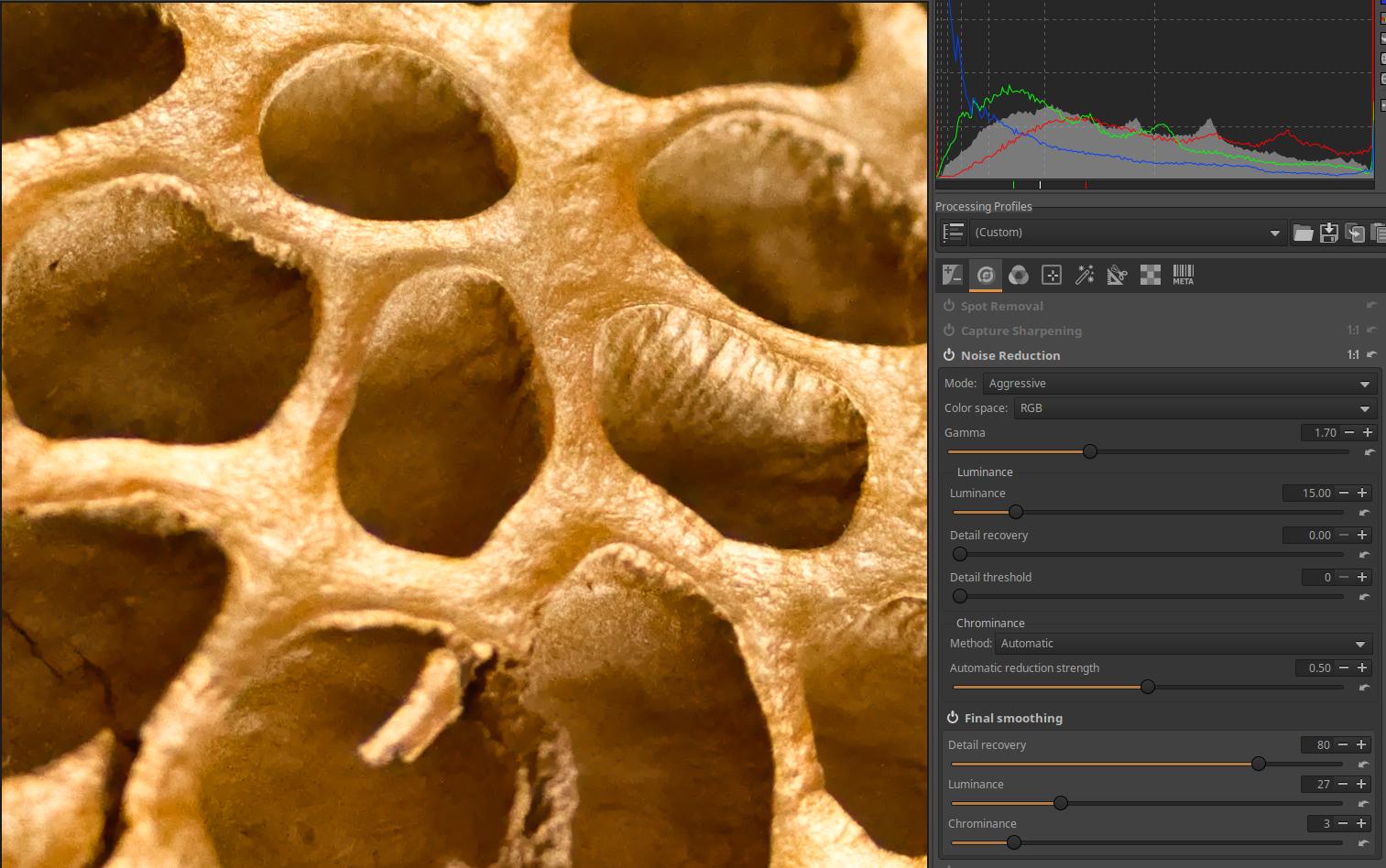

4.2.3 Noise Reduction

4.2.3.1 Luminance

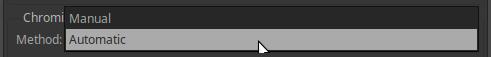

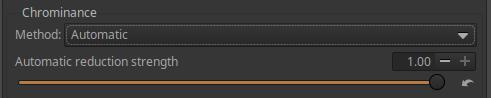

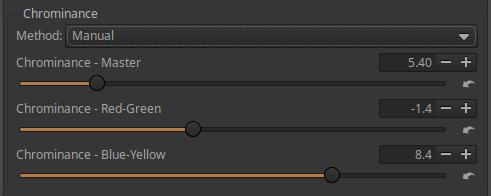

4.2.3.2 Chrominance

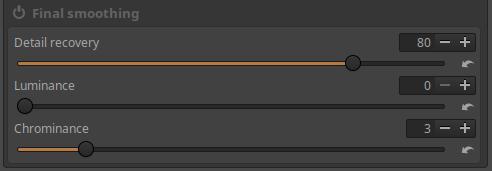

4.2.3.3 Final smoothing

4.2.4 Impulse Noise Reduction

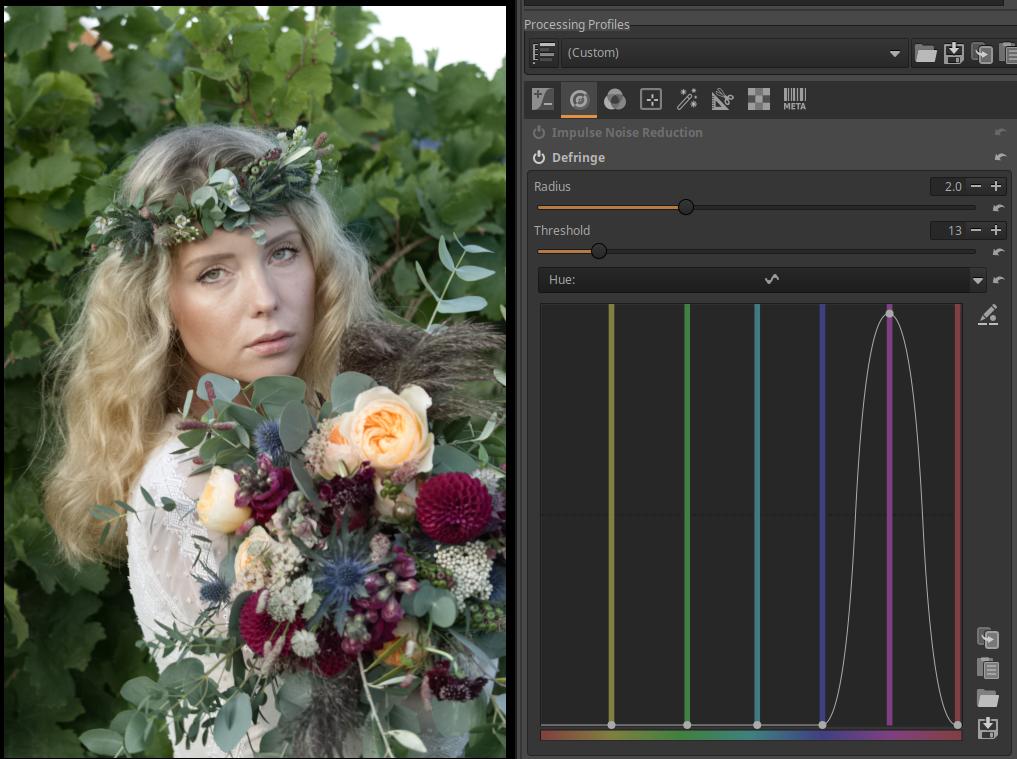

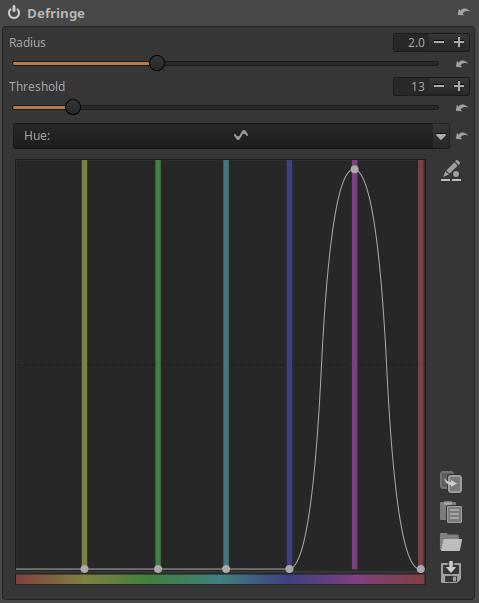

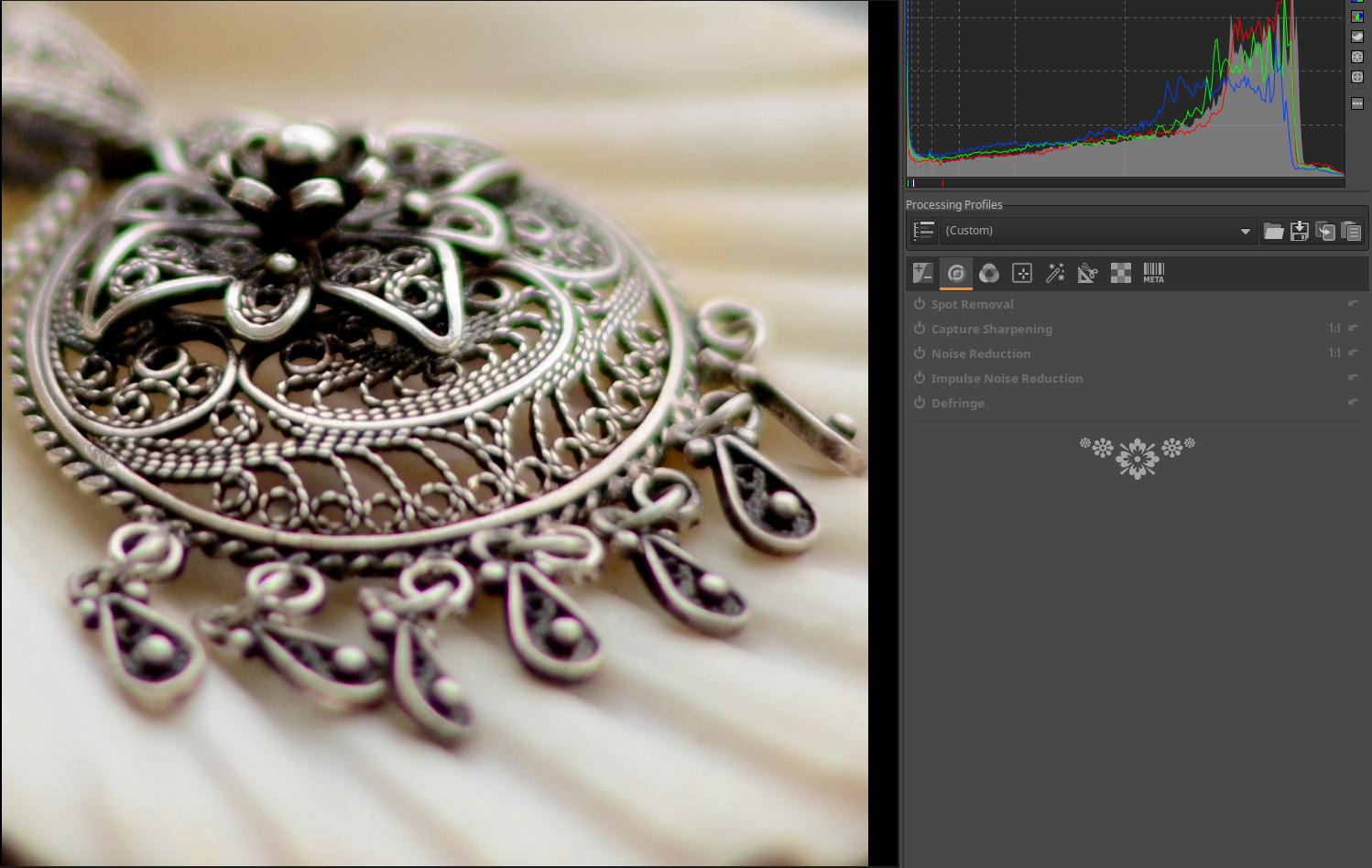

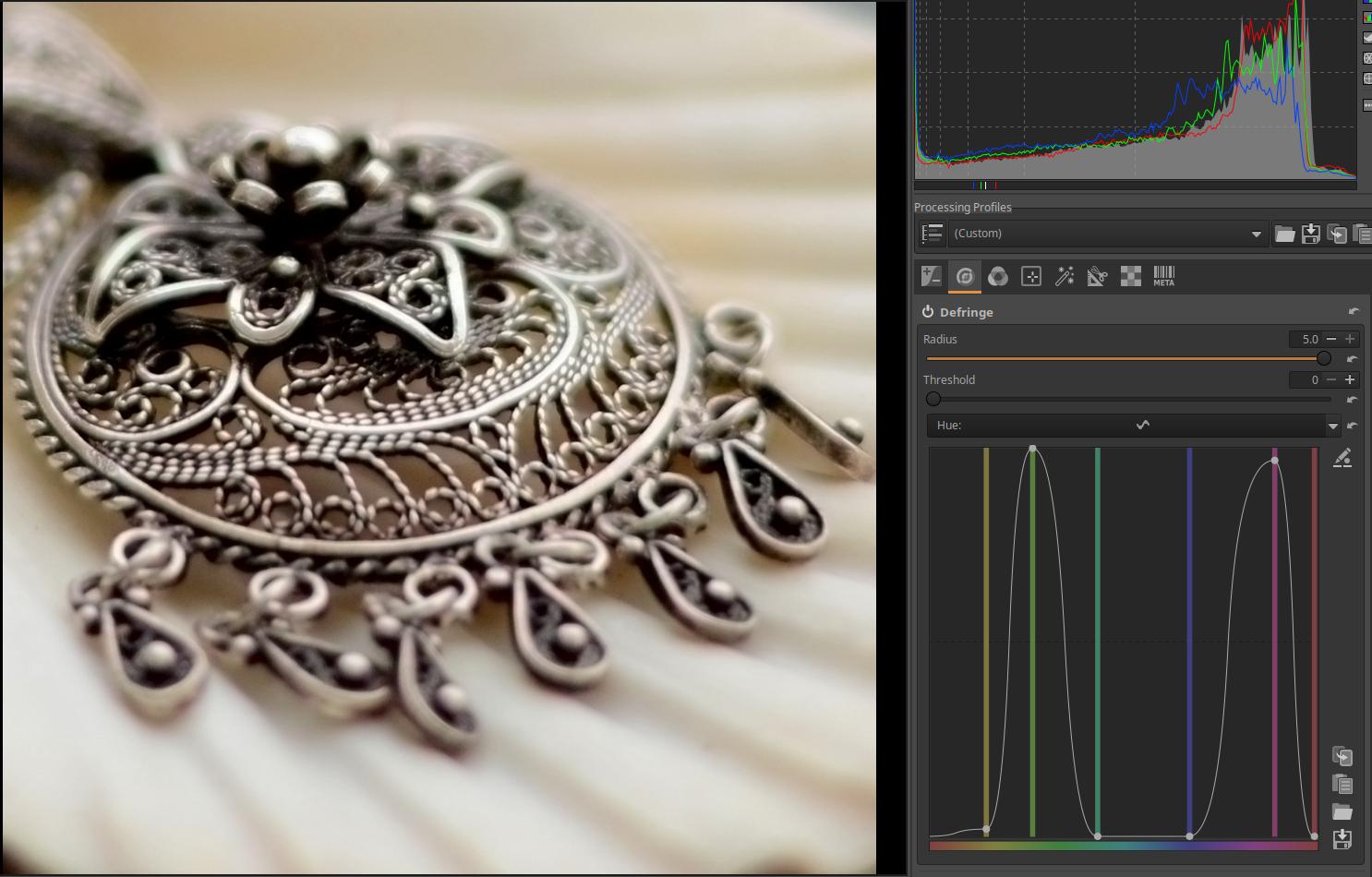

4.2.5 Defringe

4.3 Colors group

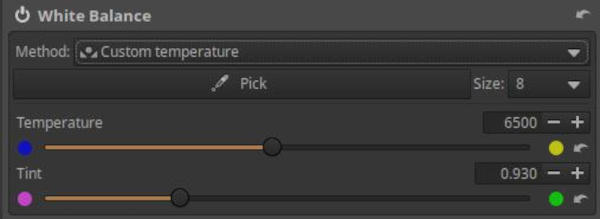

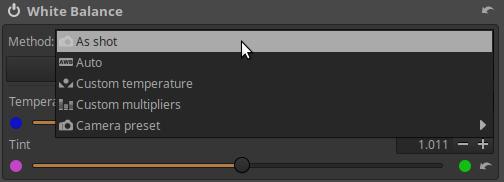

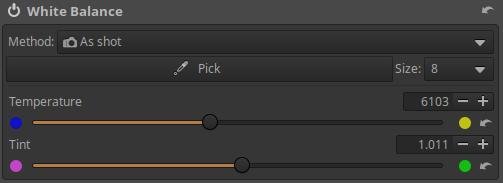

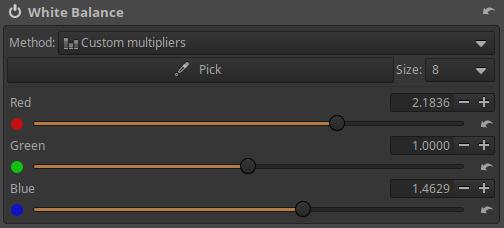

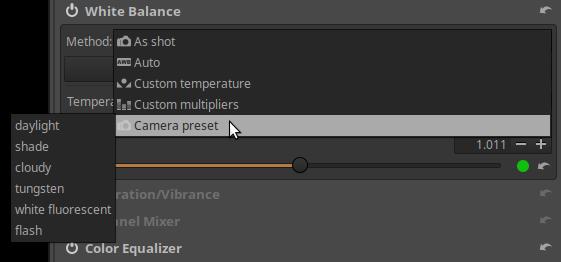

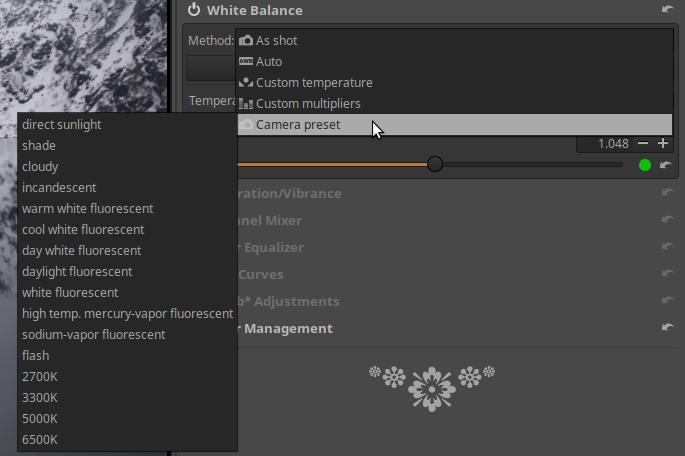

4.3.1 White Balance

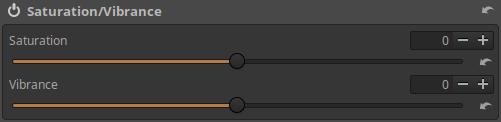

4.3.2 Saturation/Vibrance

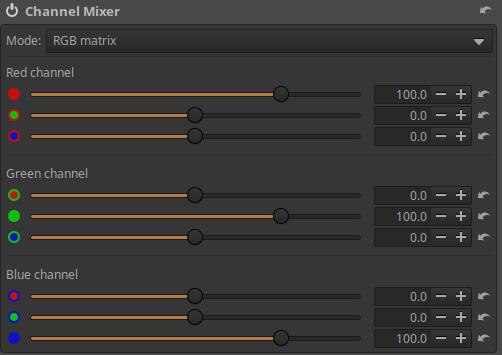

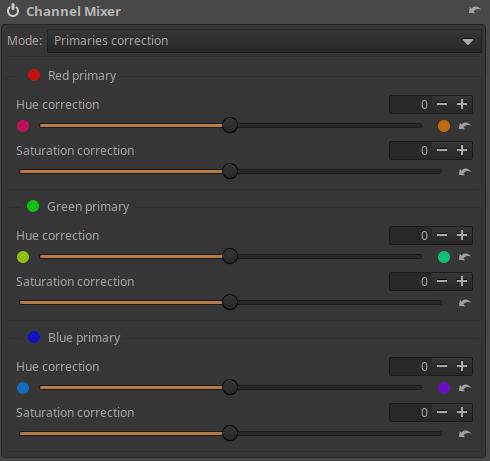

4.3.3 Channel Mixer

4.3.3.1 RGB Matrix

4.3.3.2 Primaries Correction

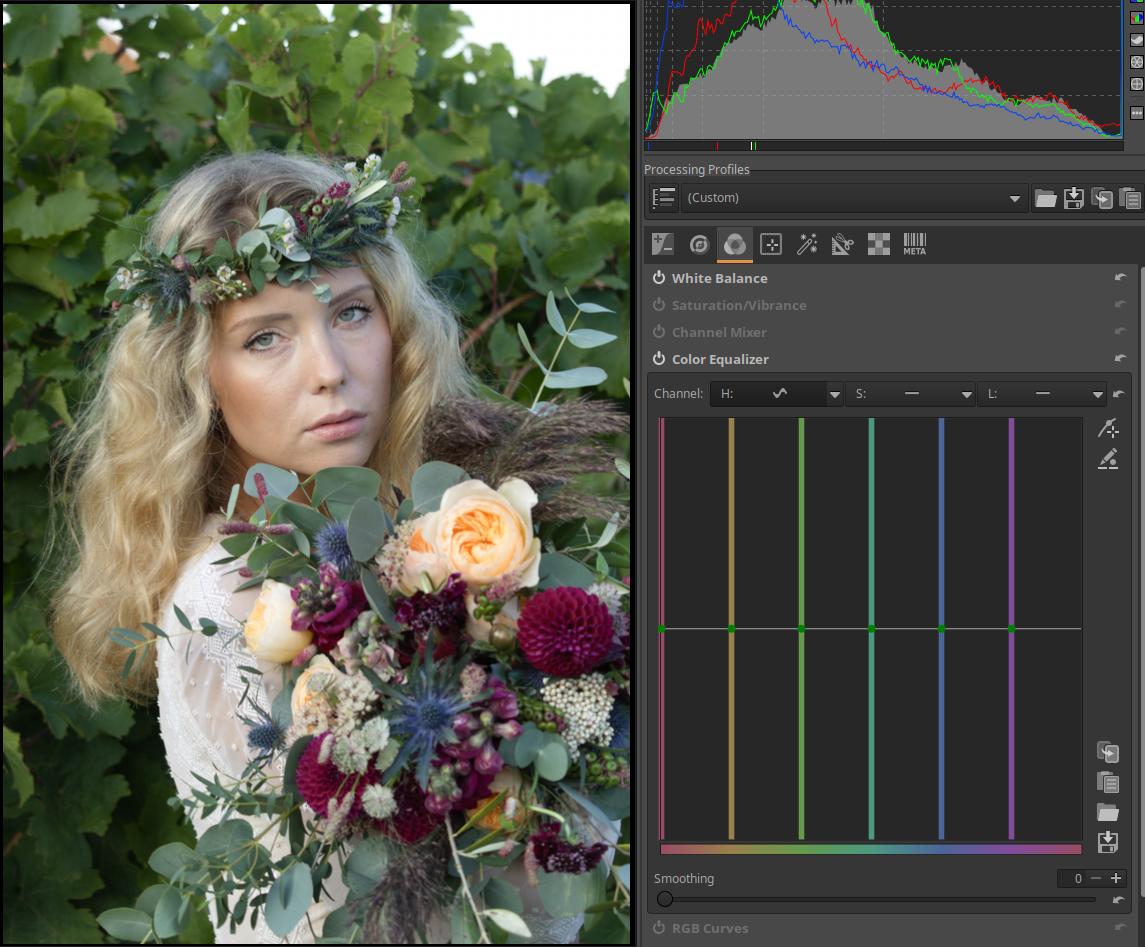

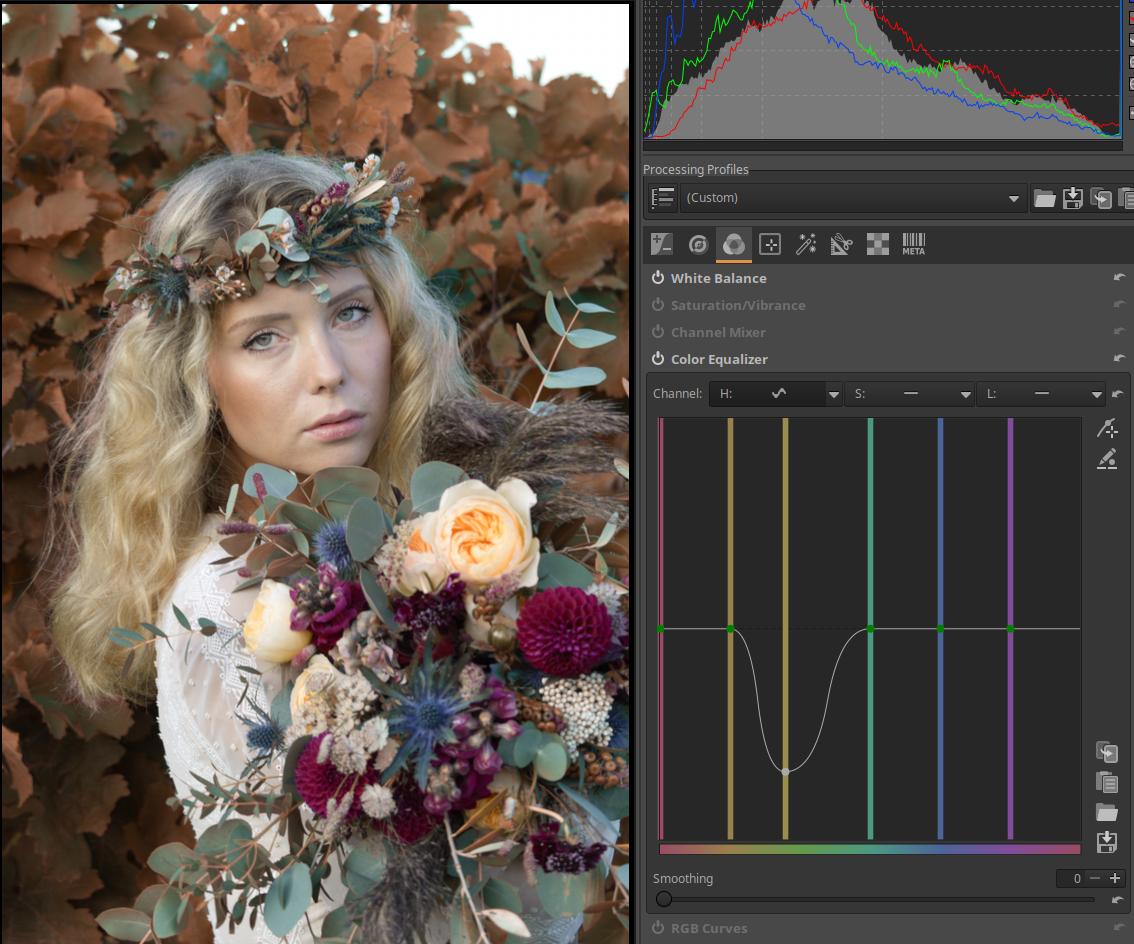

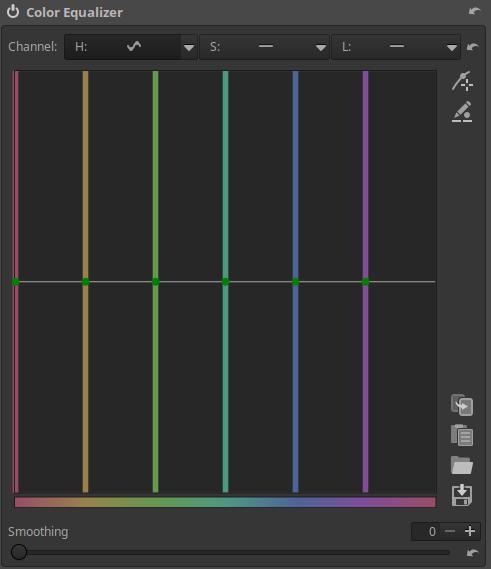

4.3.4 Color Equalizer

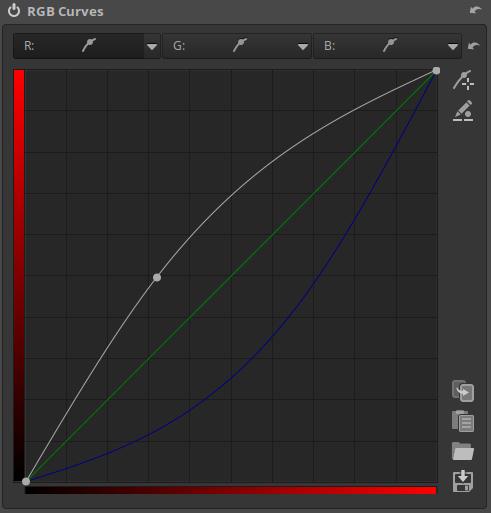

4.3.5 RGB Curves

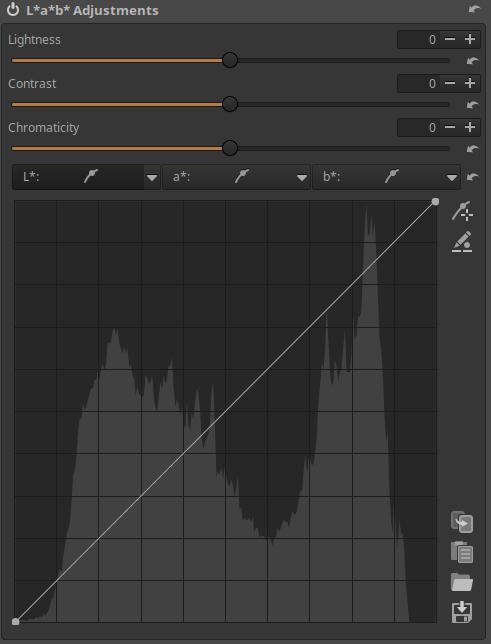

4.3.6 L*a*b* Adjustments

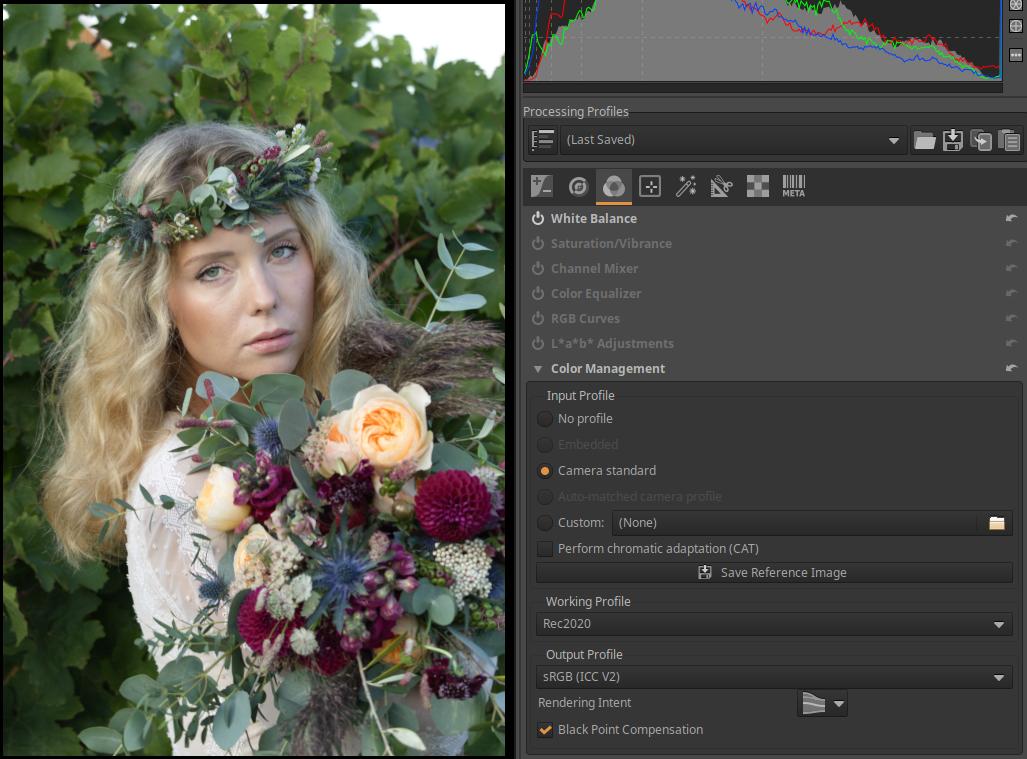

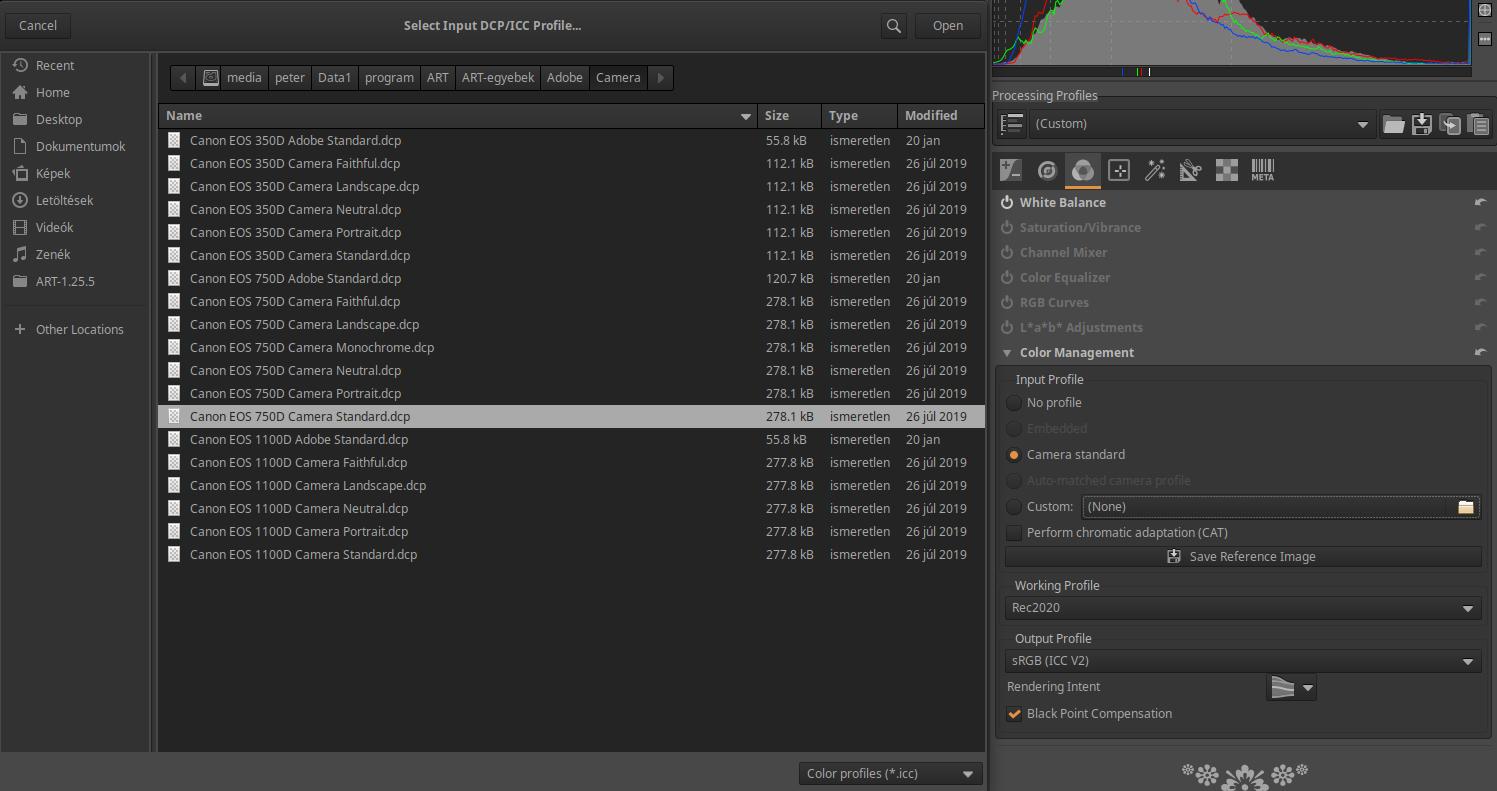

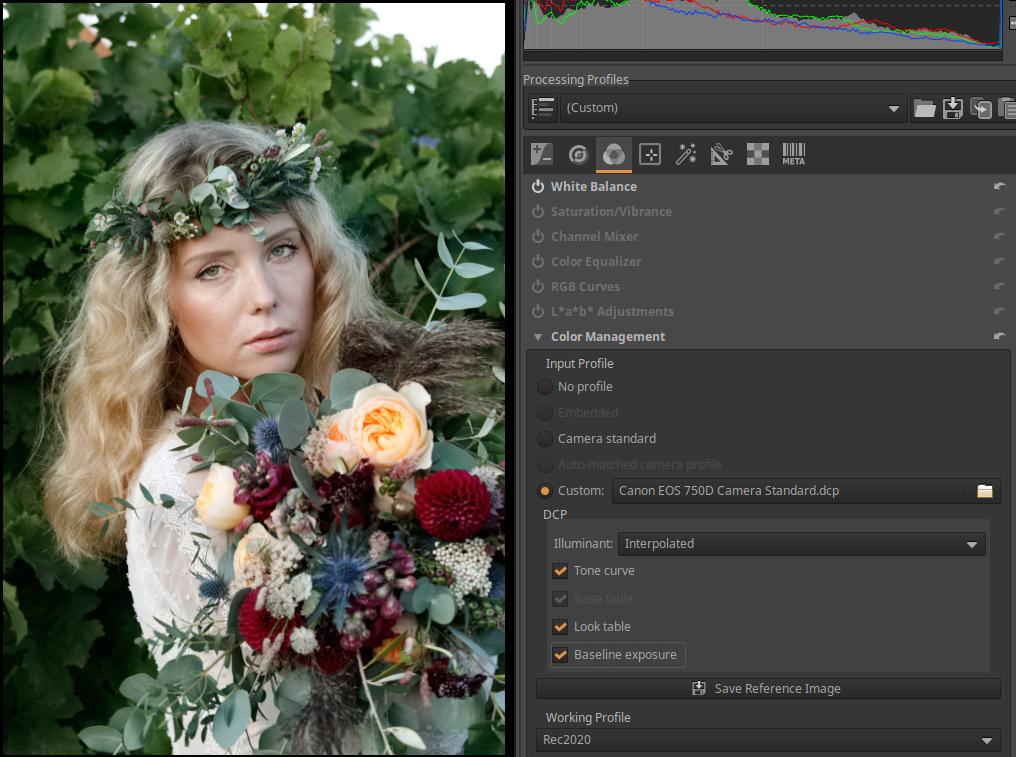

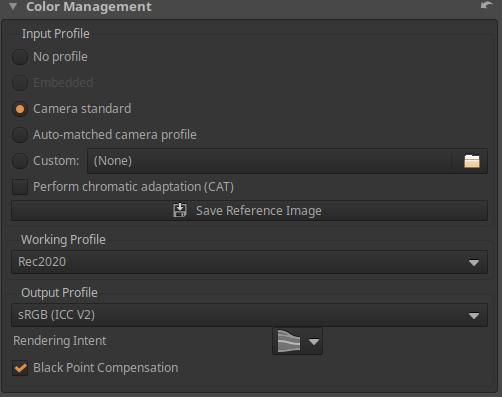

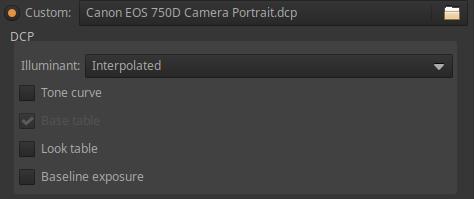

4.3.7 Color Management

4.4 Local editing group

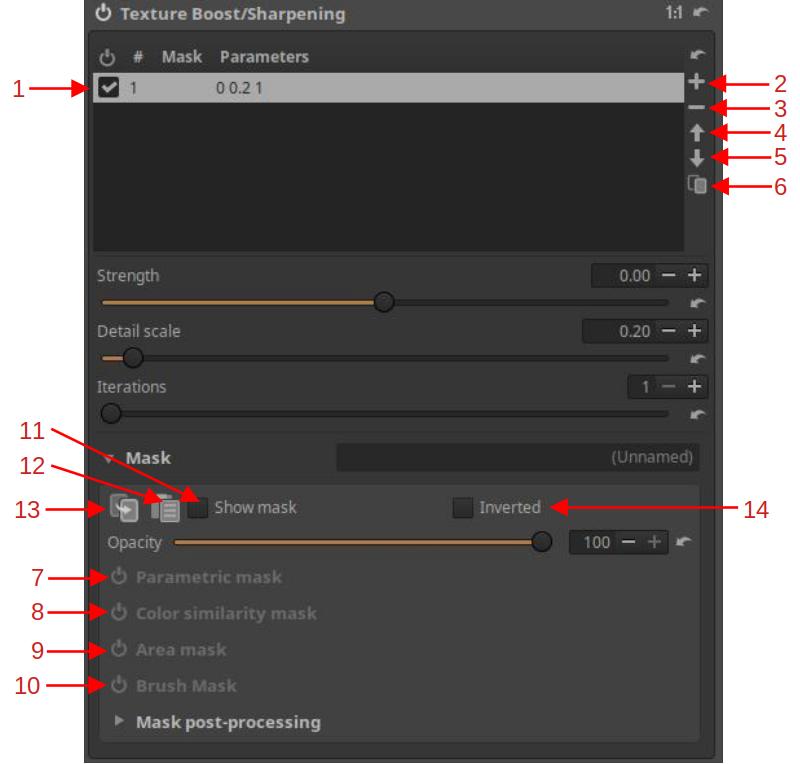

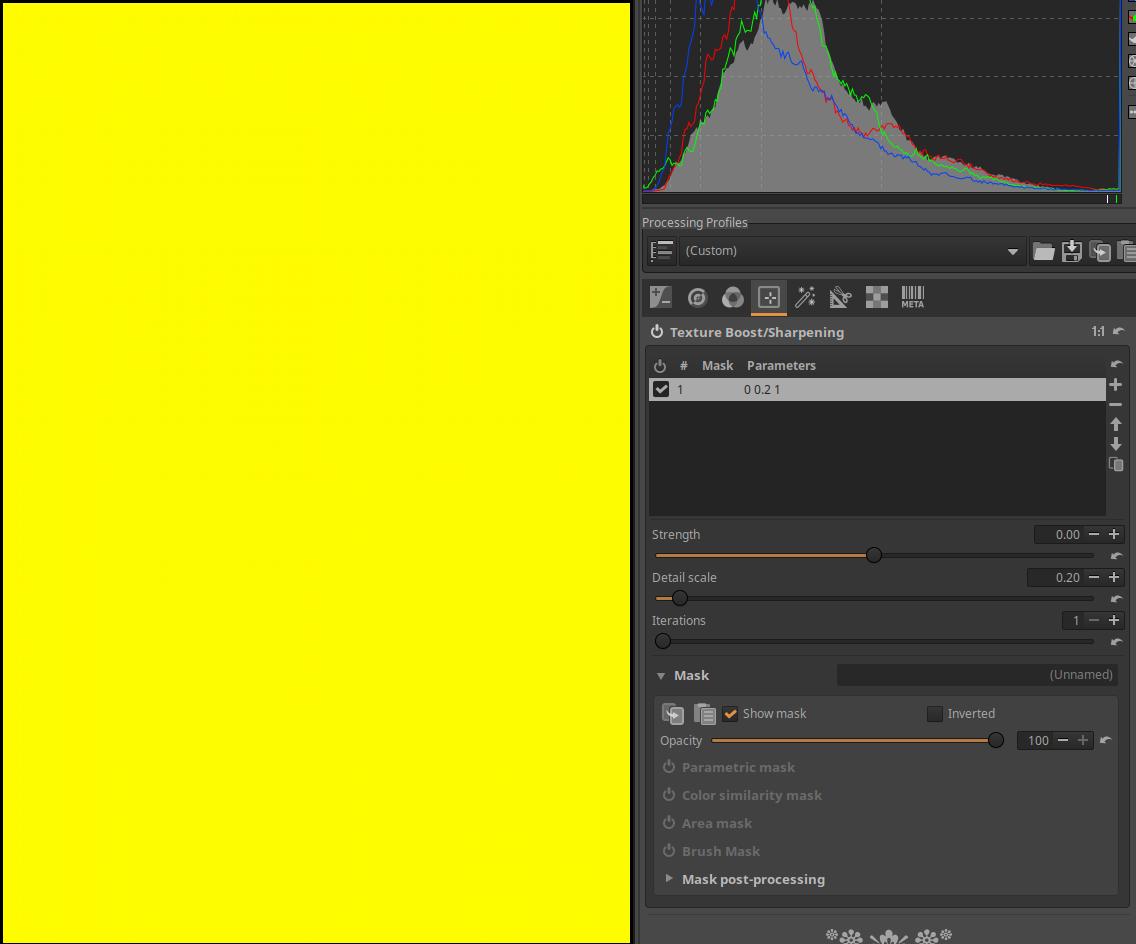

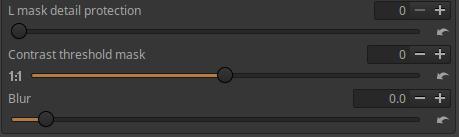

4.4.1 Masks overview

4.4.1.1 Adjustment layers

4.4.1.2 Masks

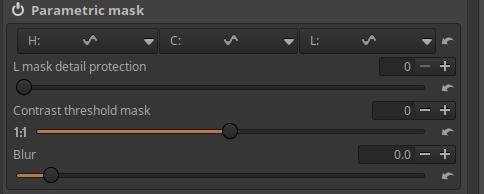

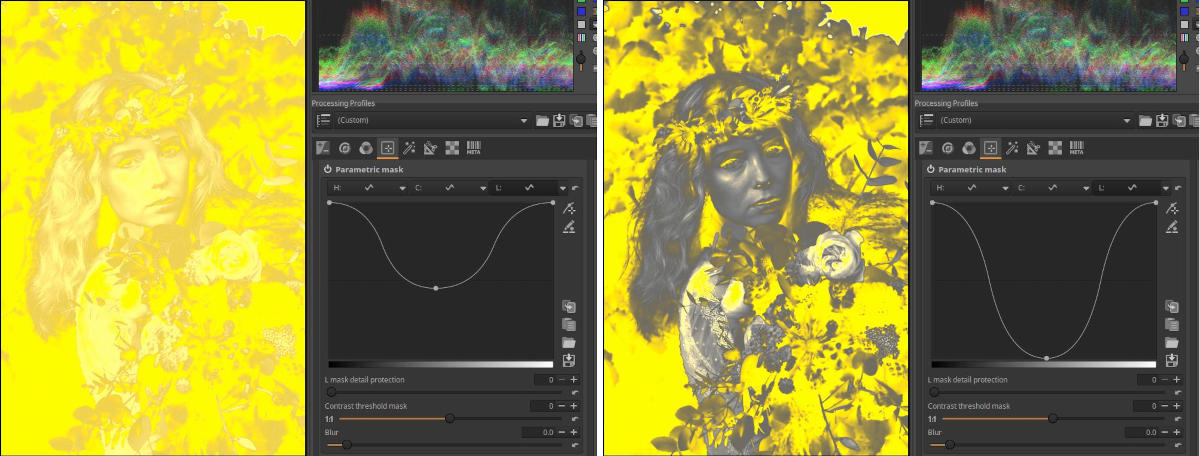

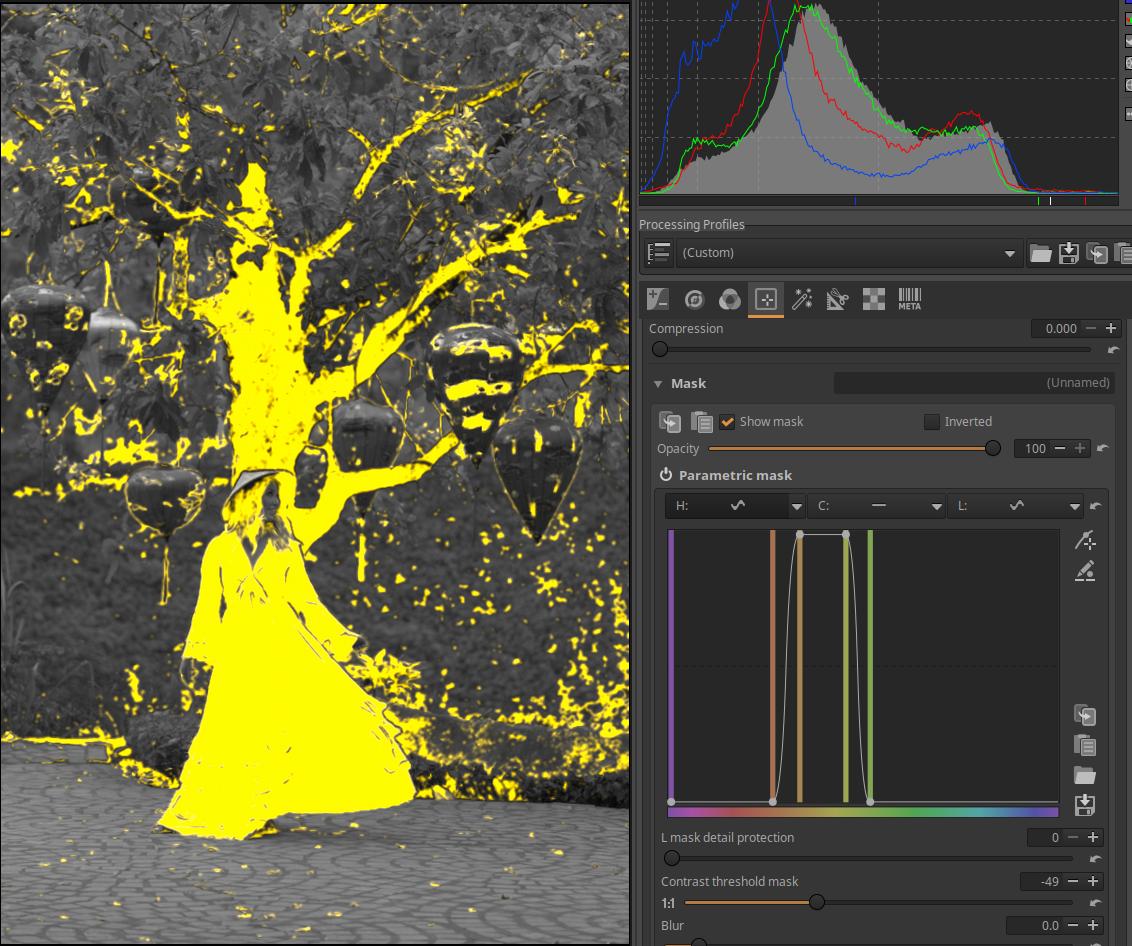

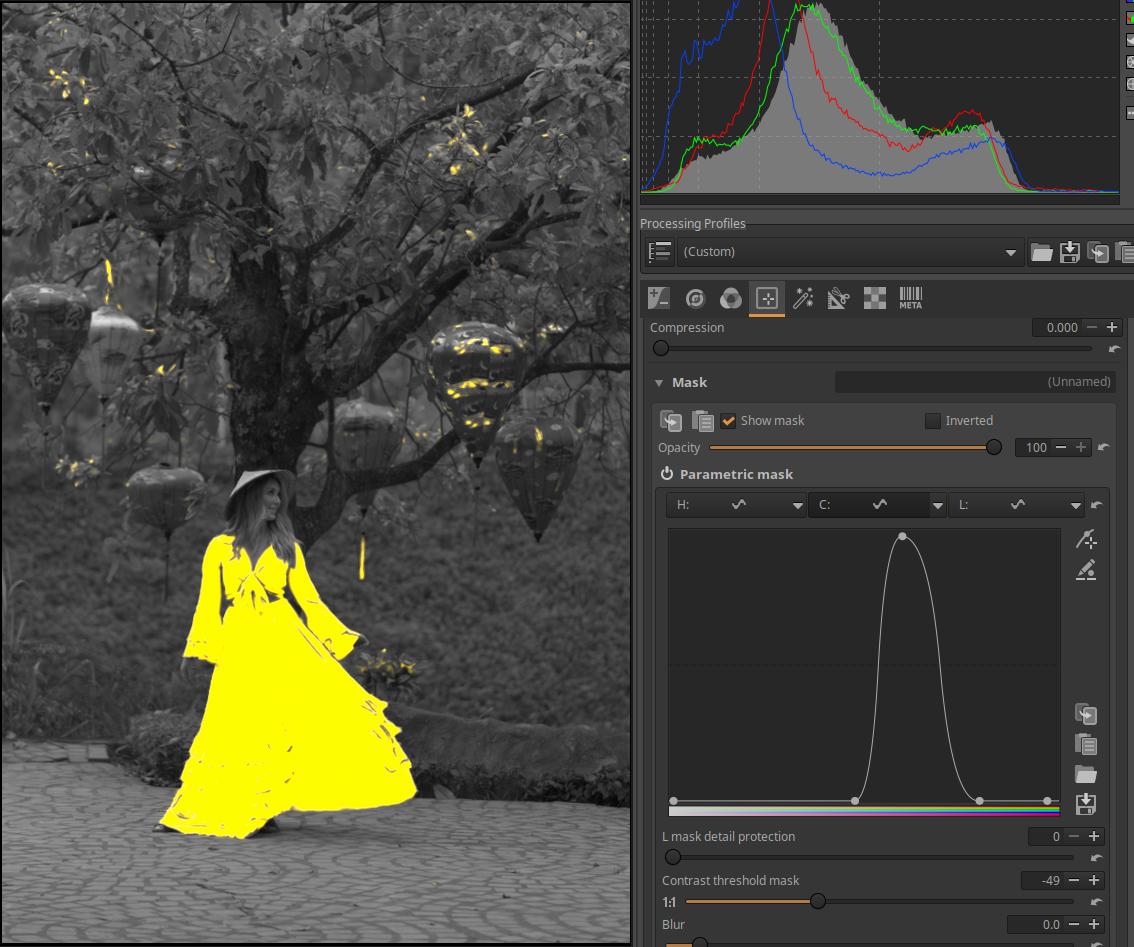

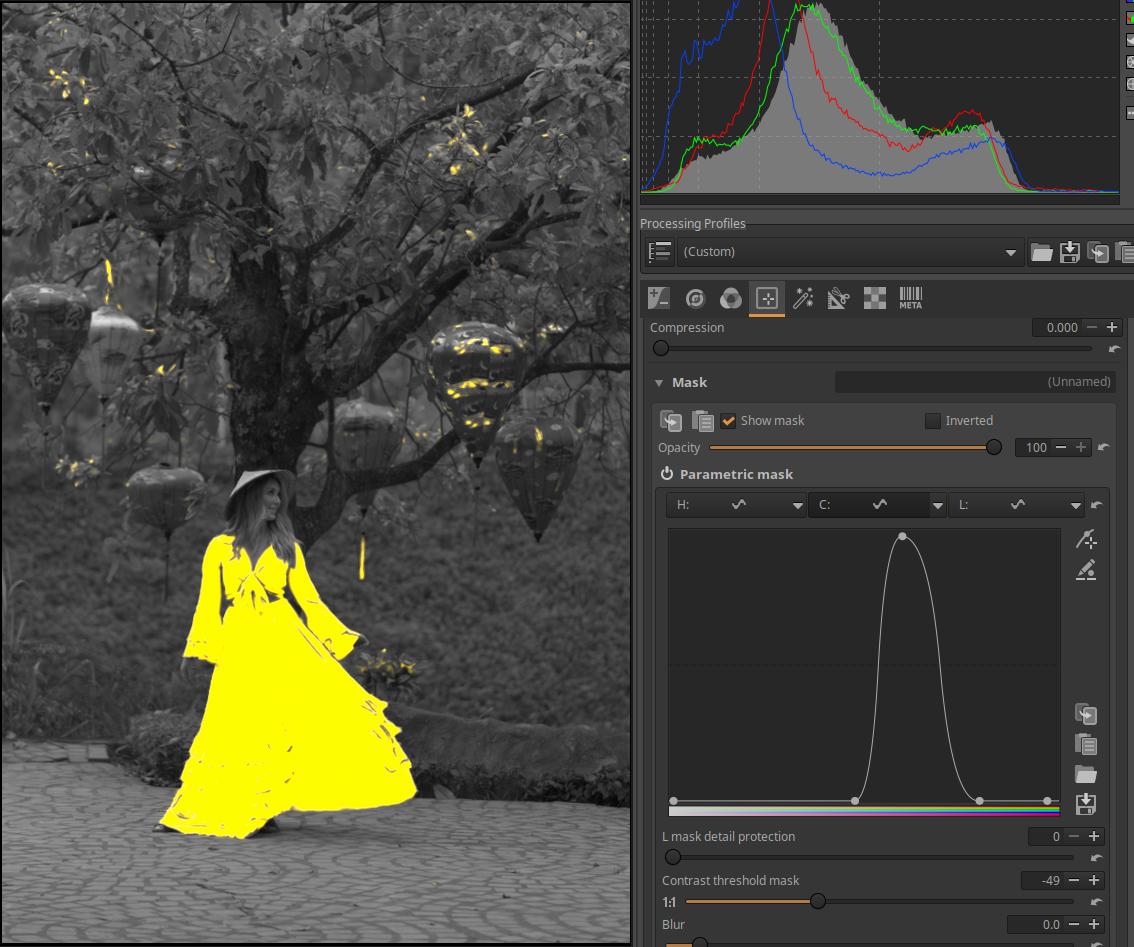

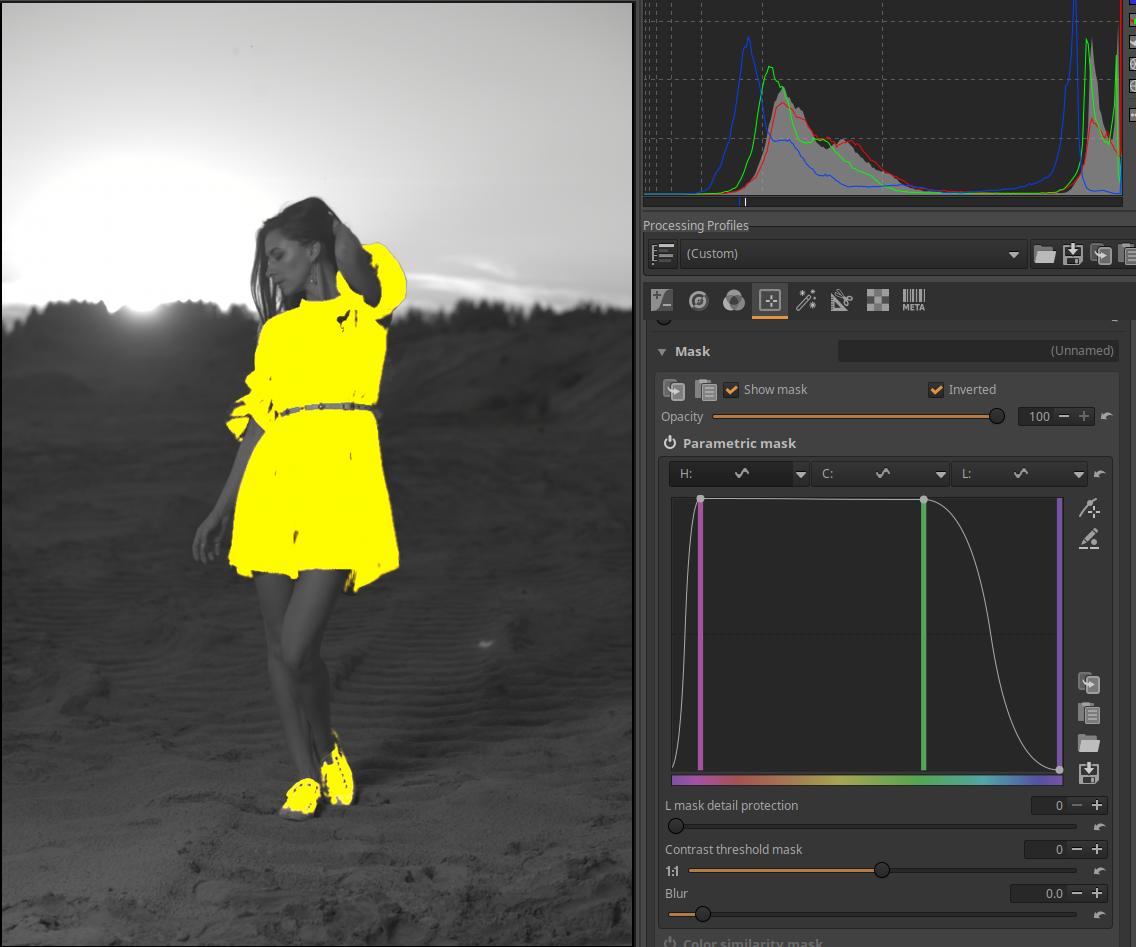

4.4.1.3 Parametric mask

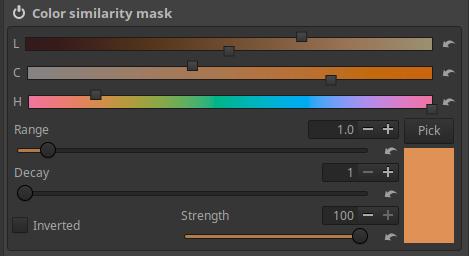

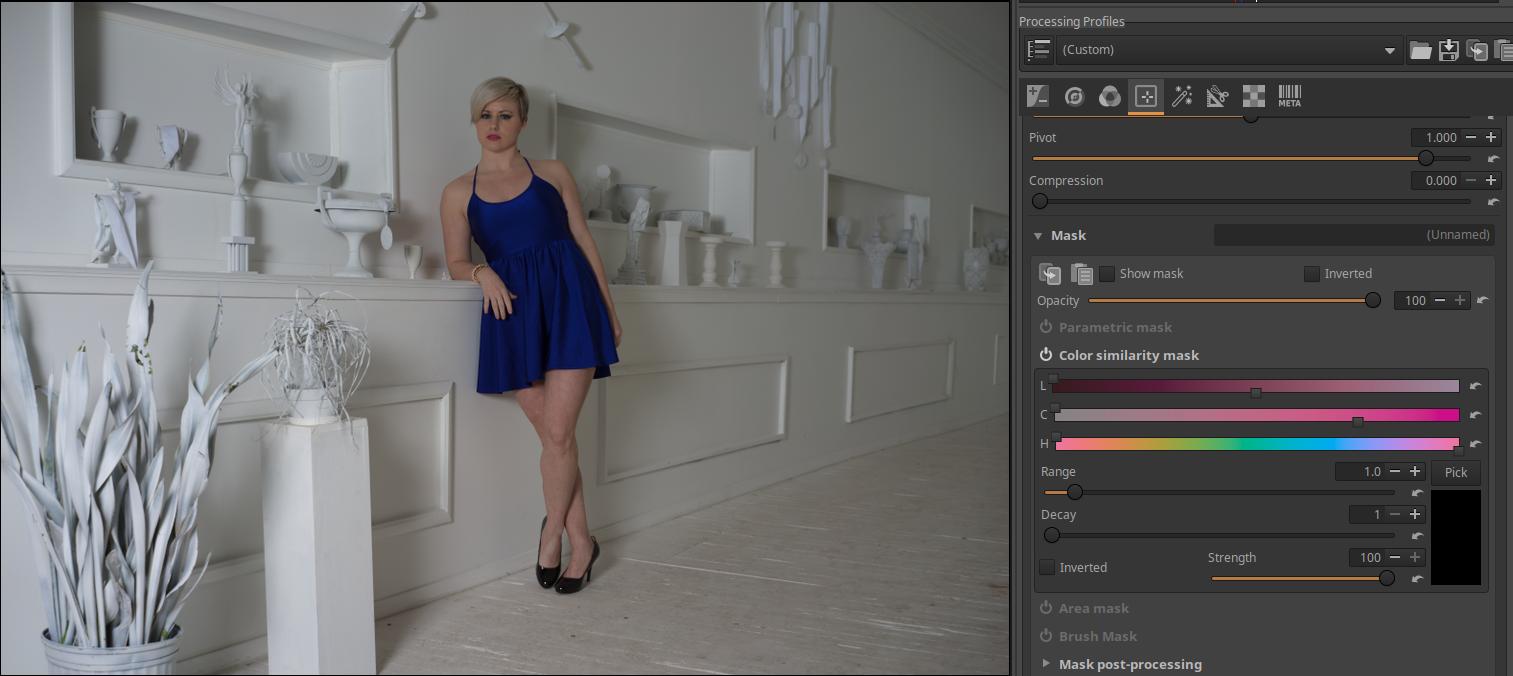

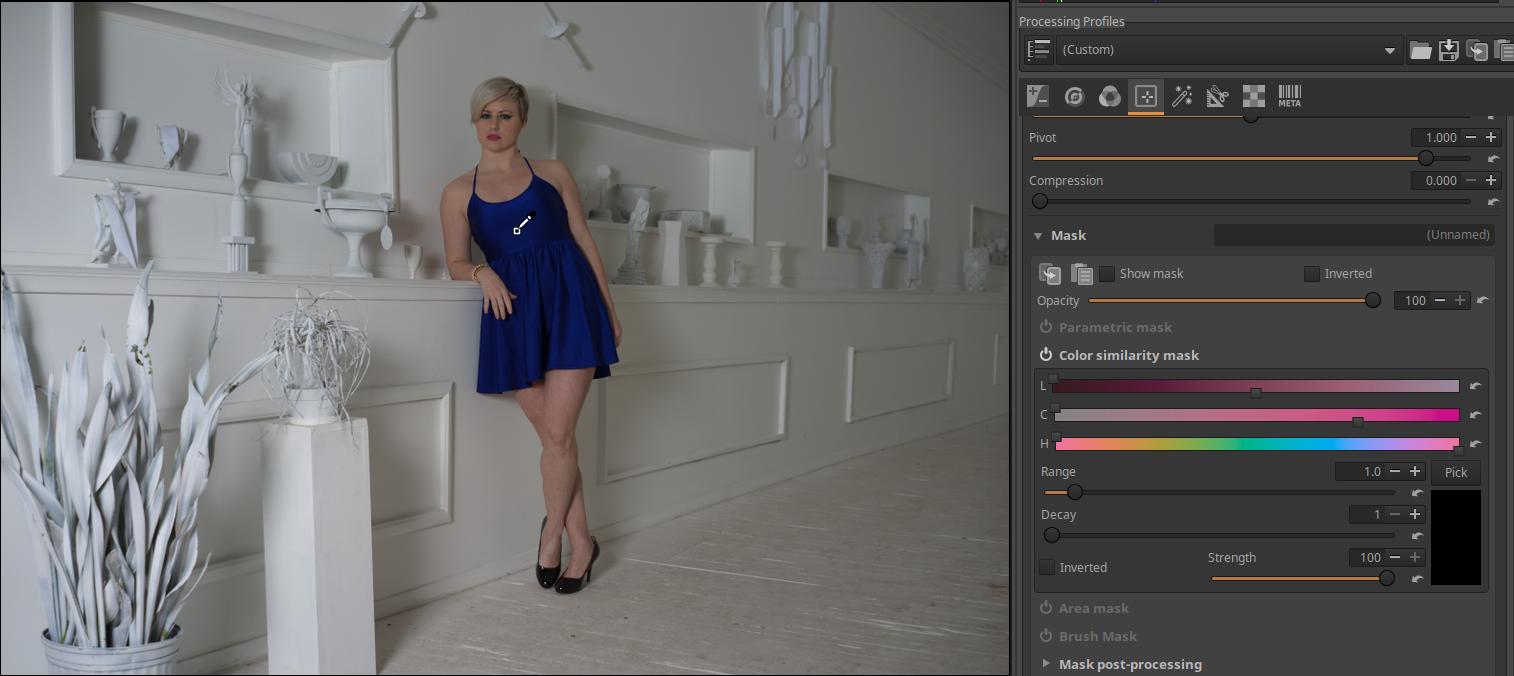

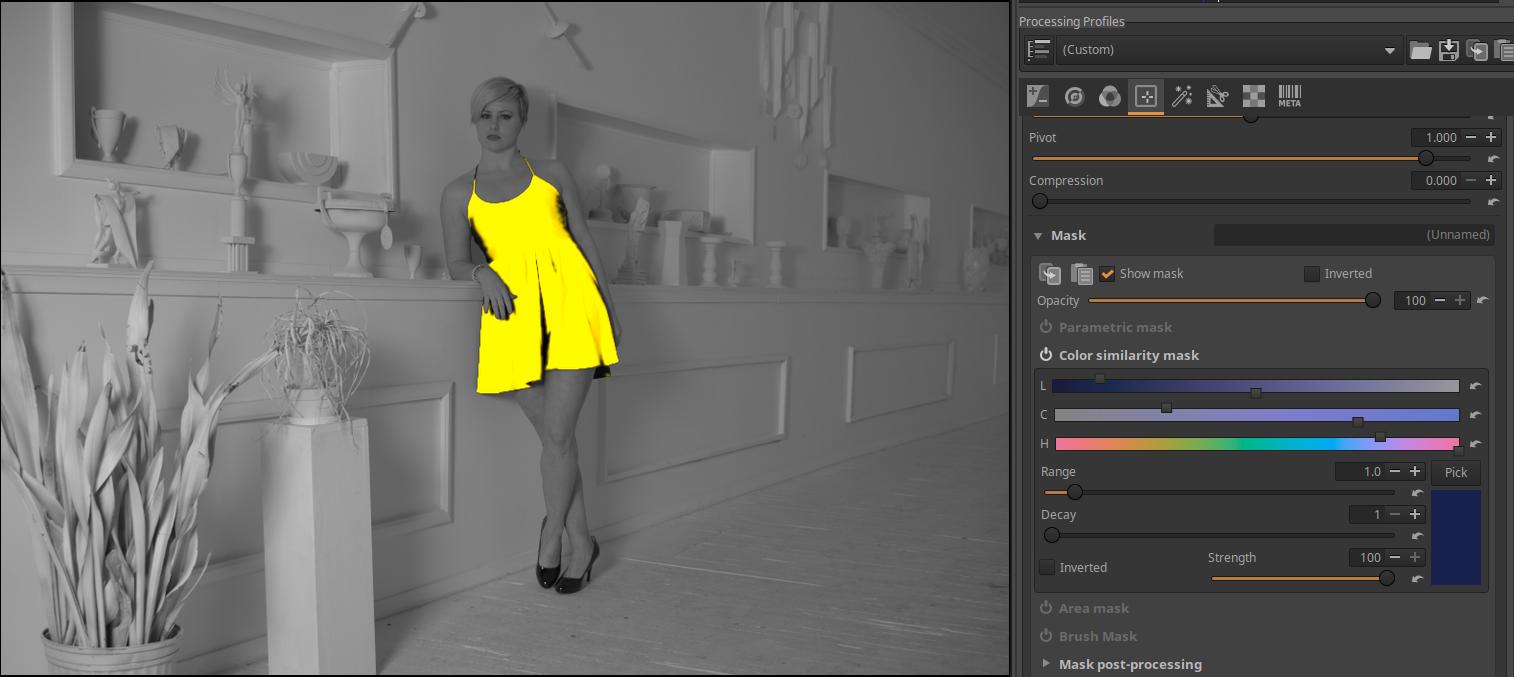

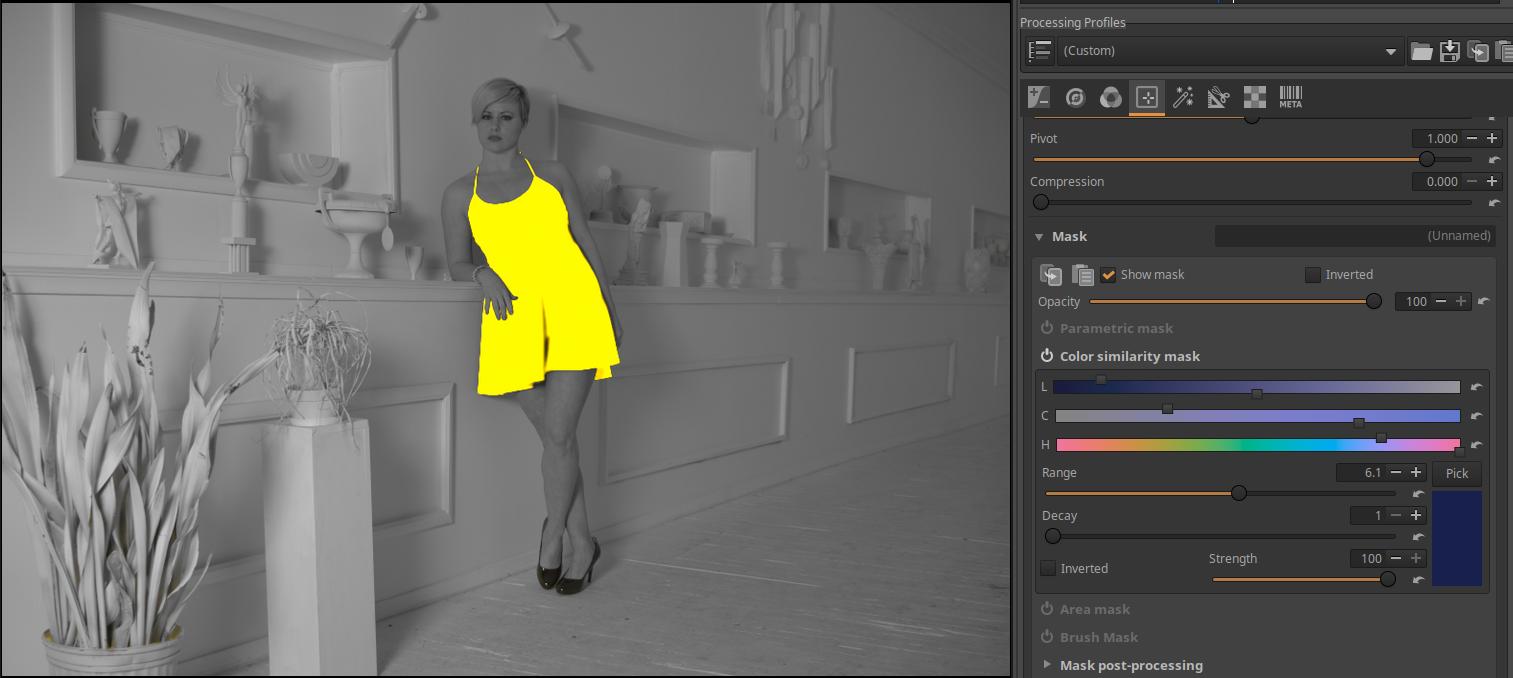

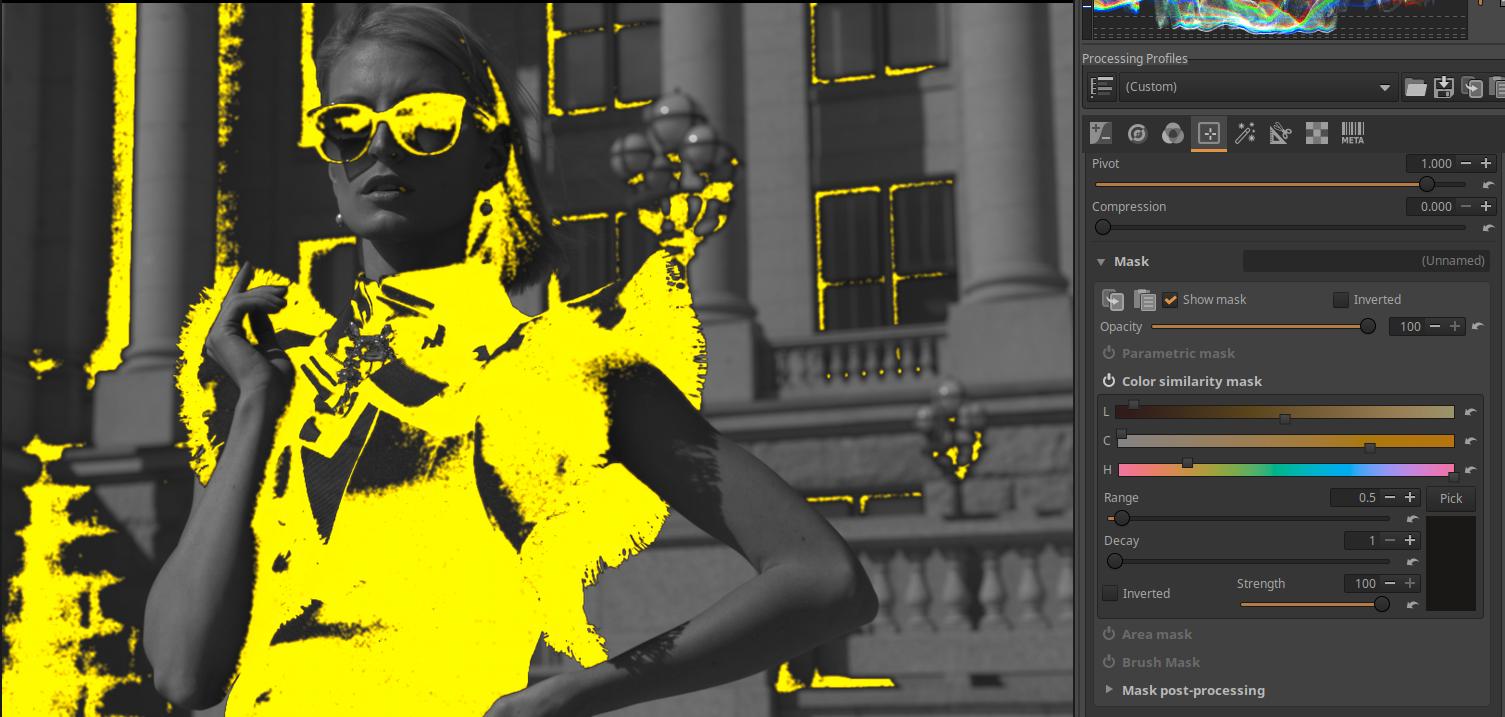

4.4.1.4 Color similarity mask

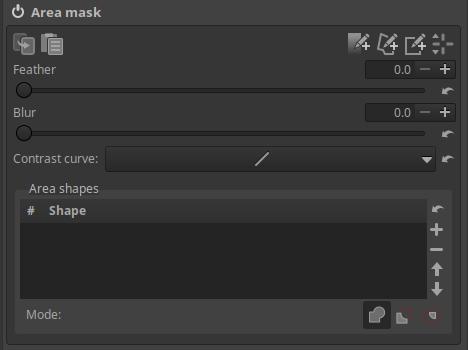

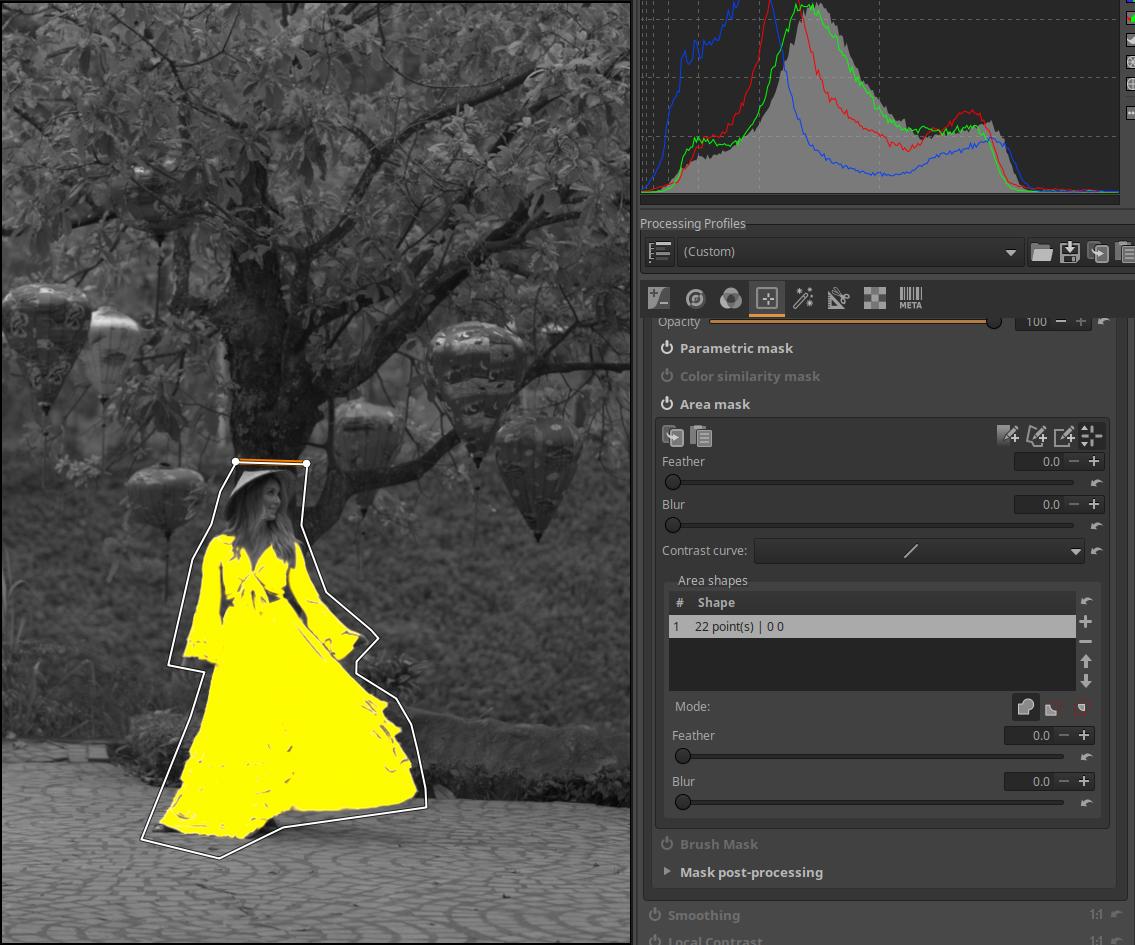

4.4.1.5 Area mask

4.4.1.5.1 Add, edit rectangle

4.4.1.5.2 Add, edit polygon

4.4.1.5.3 Add, edit gradient

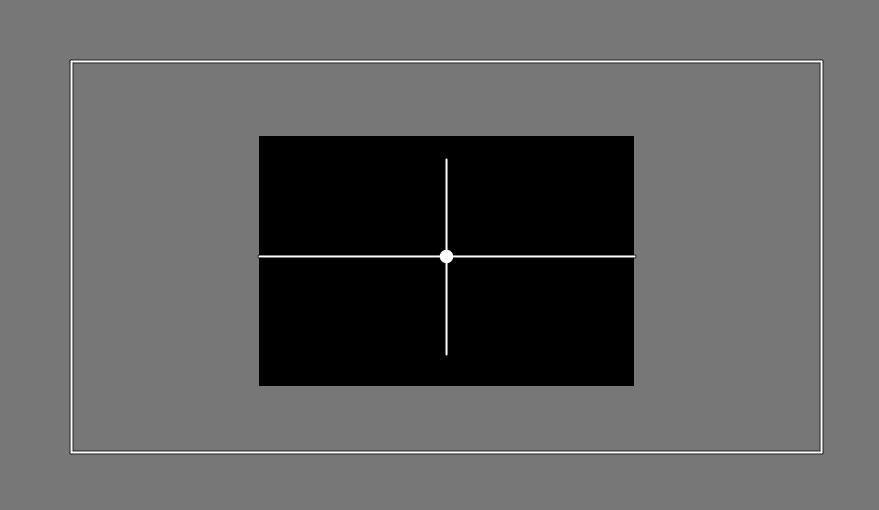

4.4.1.5.4 Area mask outside image borders

4.4.1.5.5 Excluding the area outside the area mask from the mask

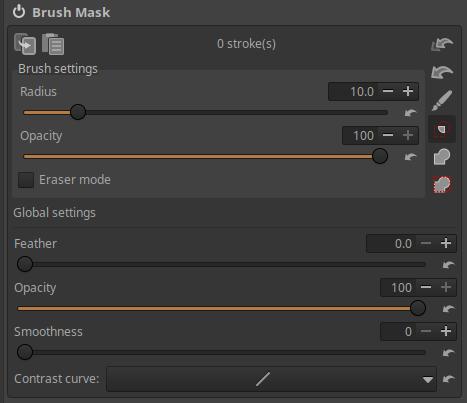

4.4.1.6 Brush mask

4.4.1.6.1 Removing unnecessary mask parts from inverted mask

4.4.1.7 Mask post-processing

4.4.1.8 Operations with masks

4.4.1.9 Creating the resultant mask

4.4.1.10 Mask precautions

4.4.1.11 Pipeline effect on masks

4.4.1.11.1 Different masks within the same editing tool

4.4.1.11.2 Copy masks between Local editing tools

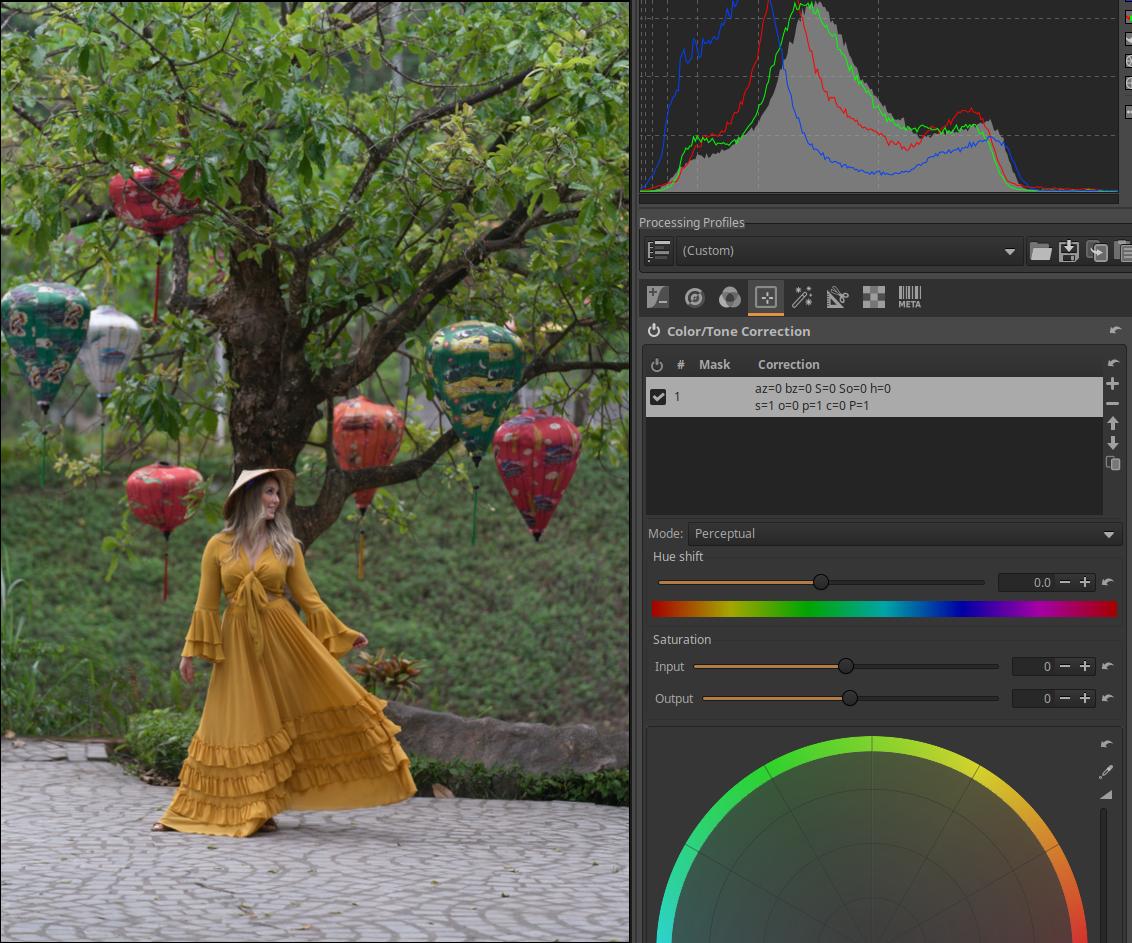

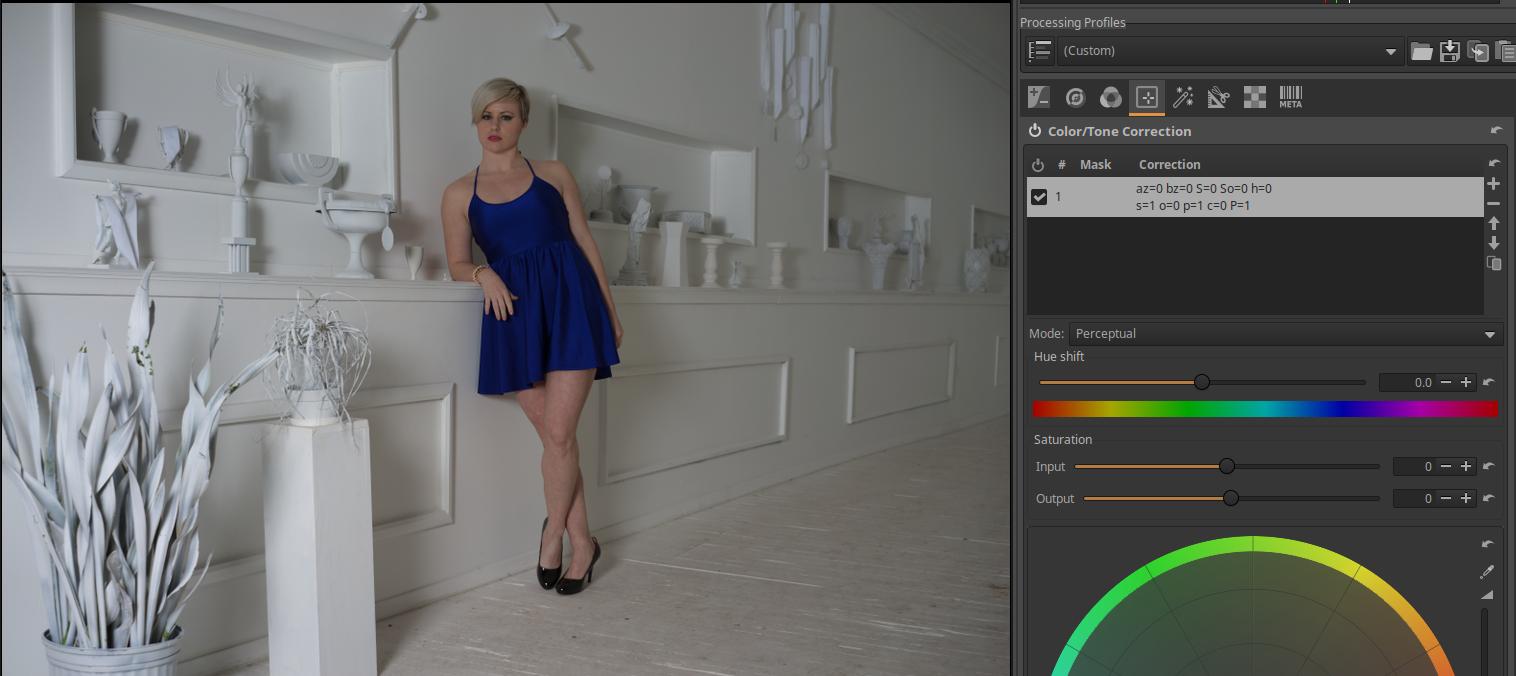

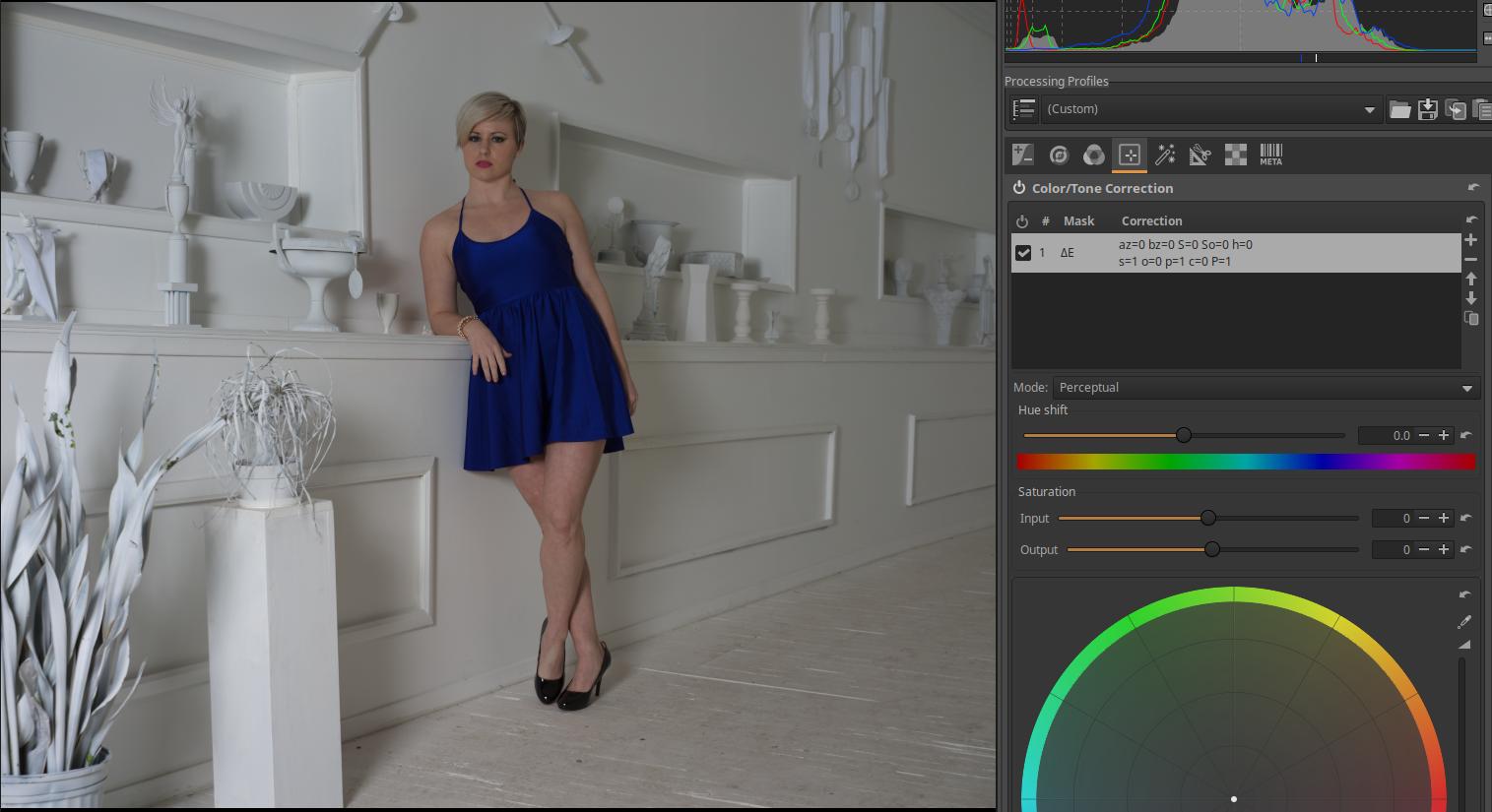

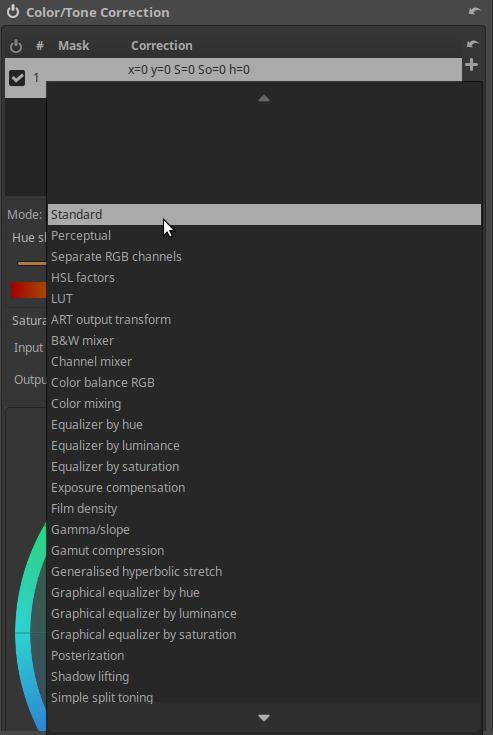

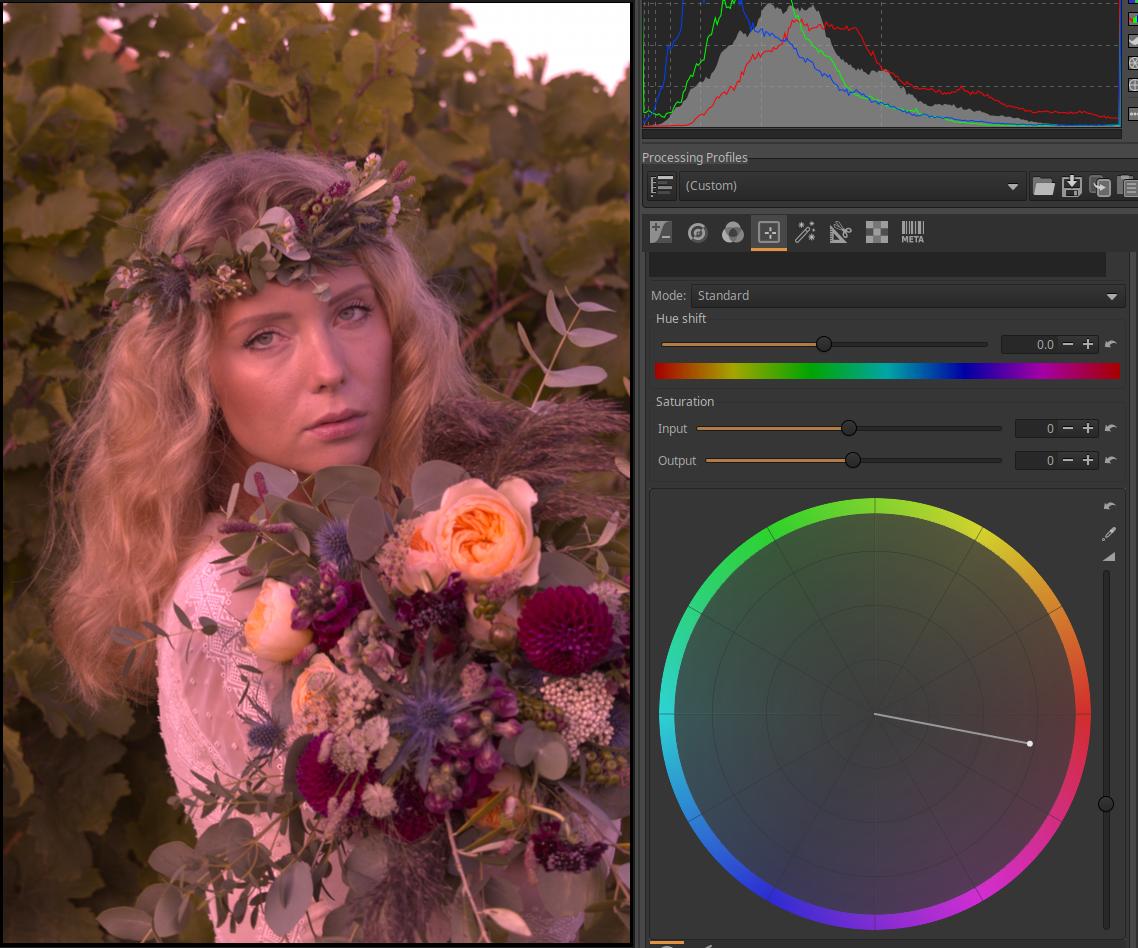

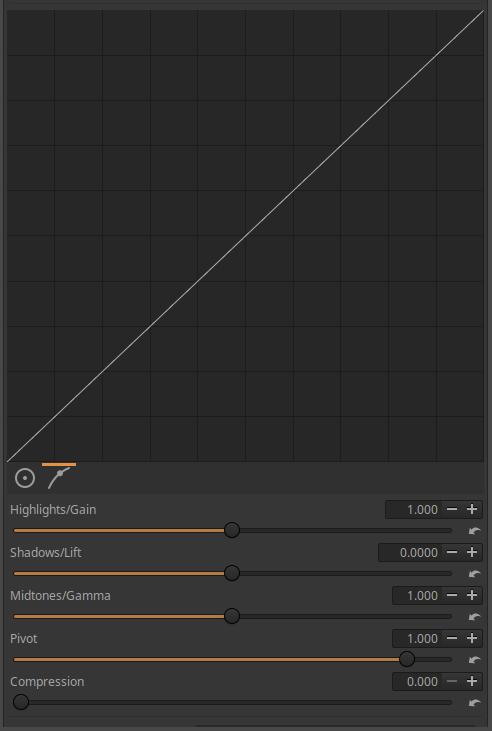

4.4.2 Color/Tone Correction

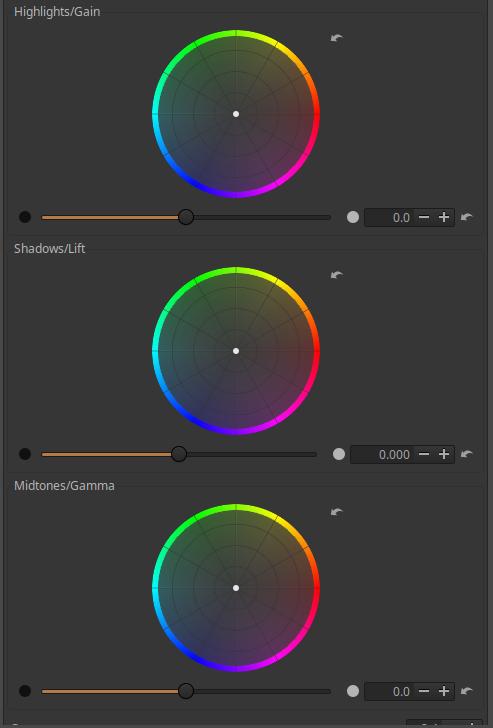

4.4.2.1 Standard and Perceptual

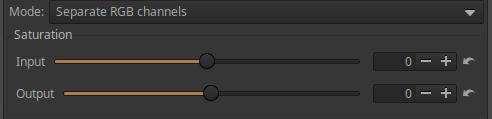

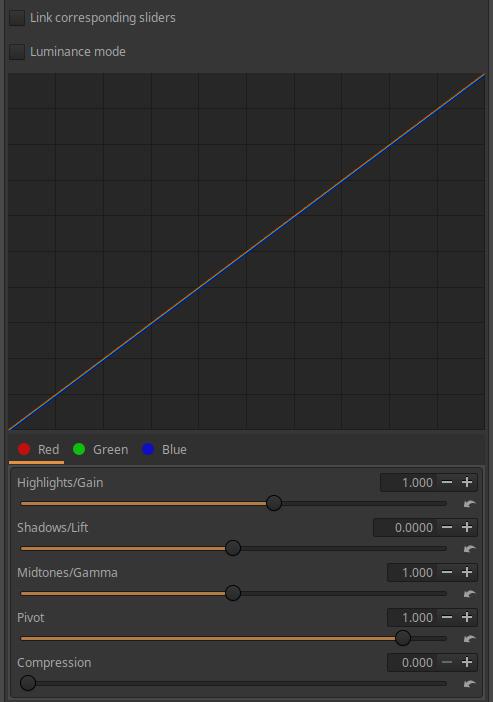

4.4.2.2 Separate RGB channels

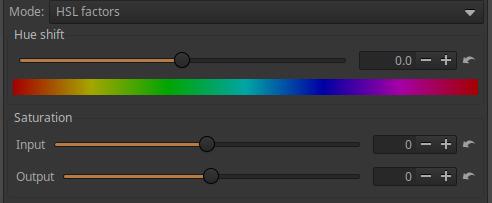

4.4.2.3 HSL factors

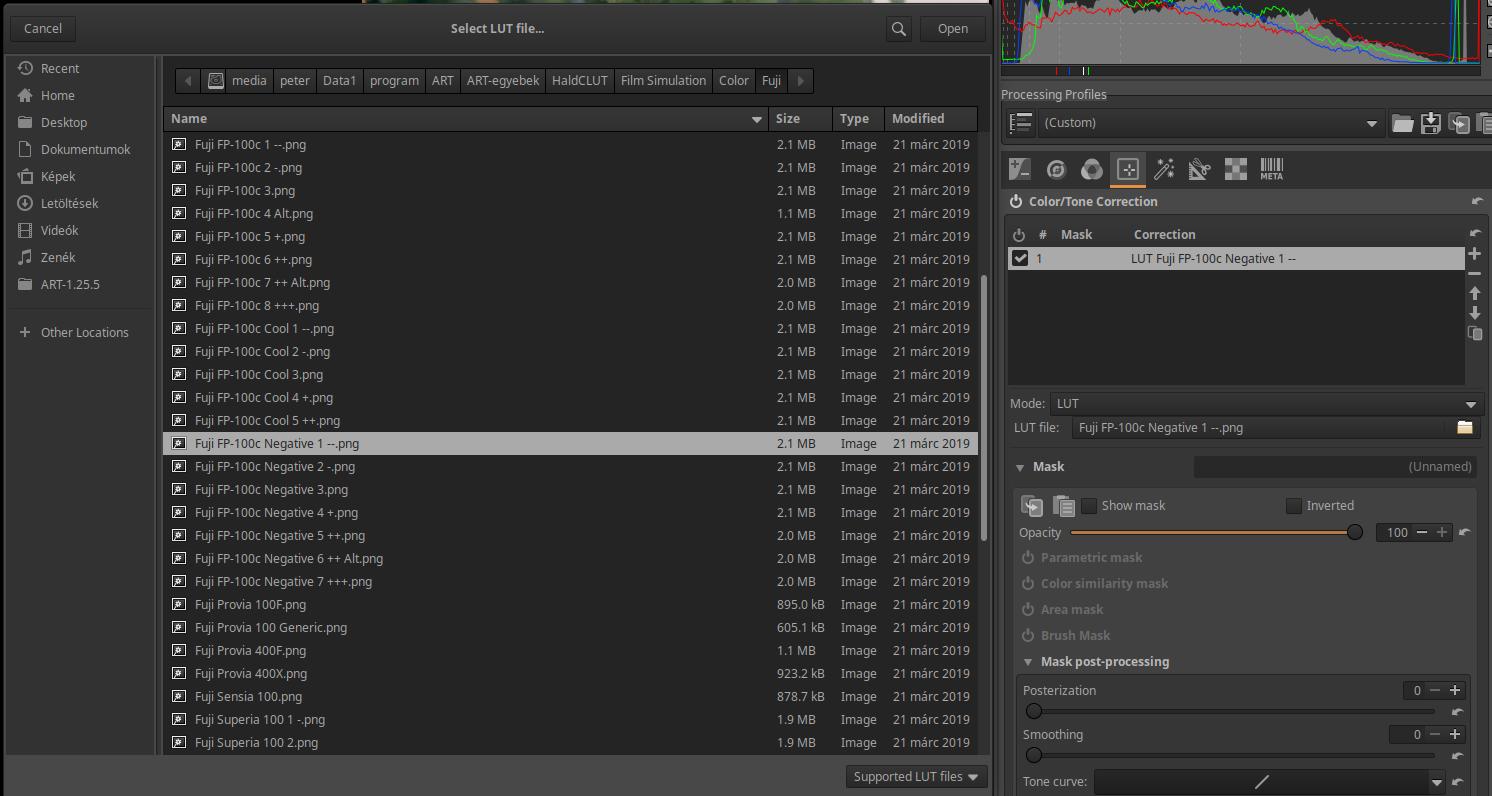

4.4.2.4 LUT

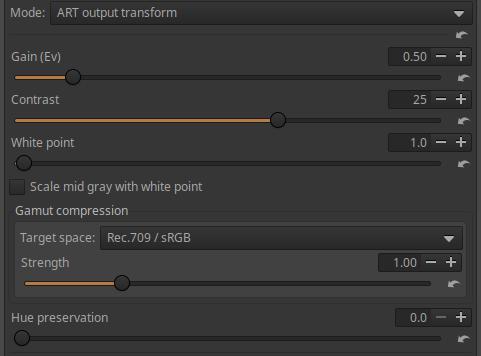

4.4.2.7 ART output transform CTL script

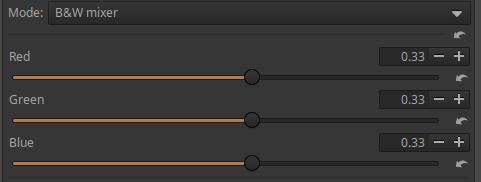

4.4.2.12 B&W mixer CTL script

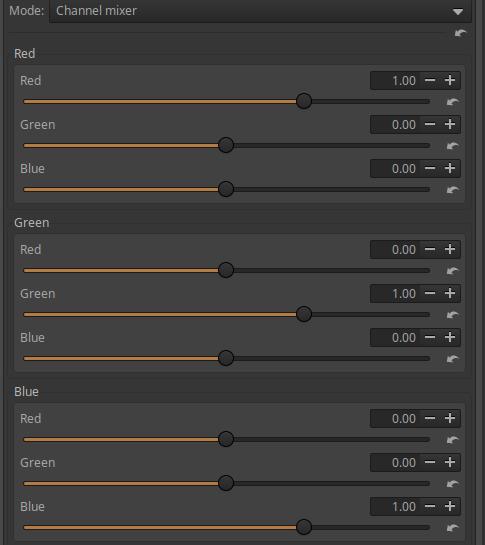

4.4.2.8 Channel mixer CTL script

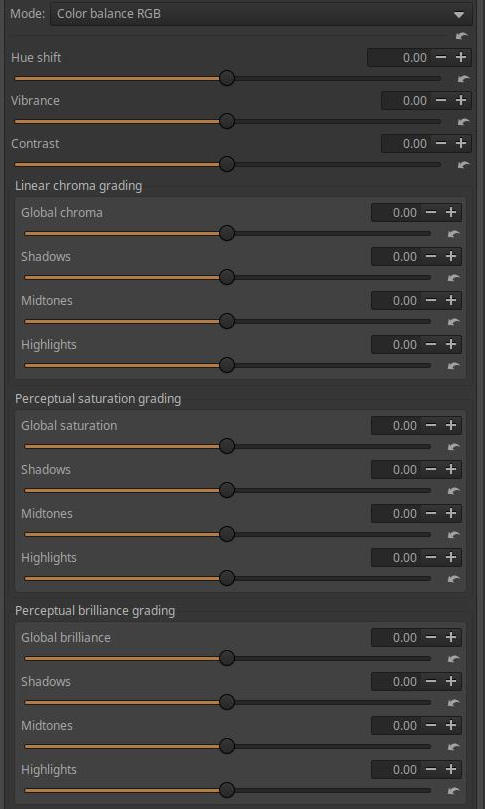

4.4.2.20 Color balance RGB CTL script

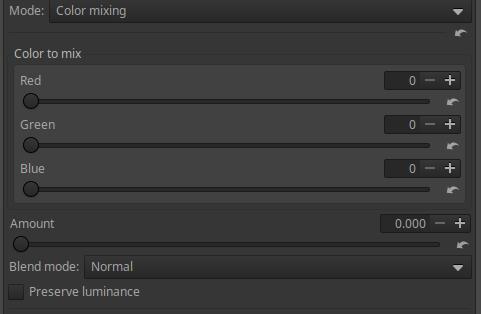

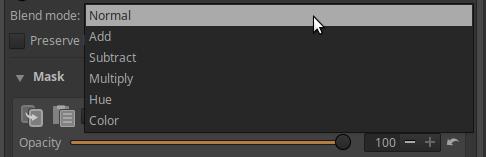

4.4.2.21 Color mixing CTL script

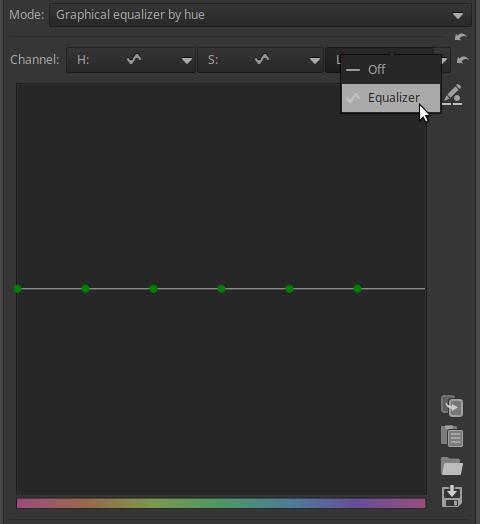

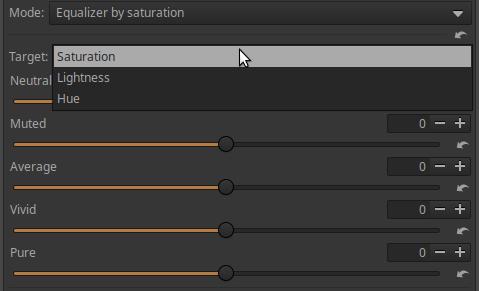

4.4.2.15 Equalizer CTL scripts

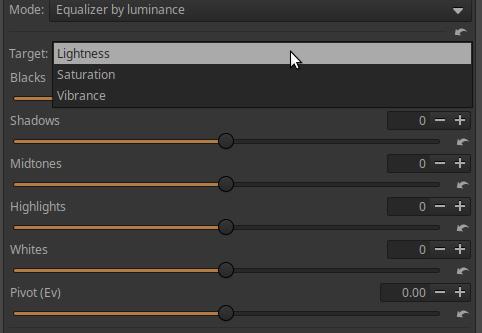

4.4.2.10 Exposure compensation CTL script

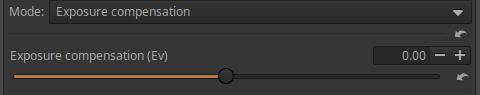

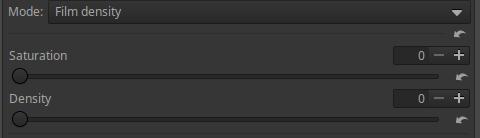

4.4.2.13 Film density CTL script

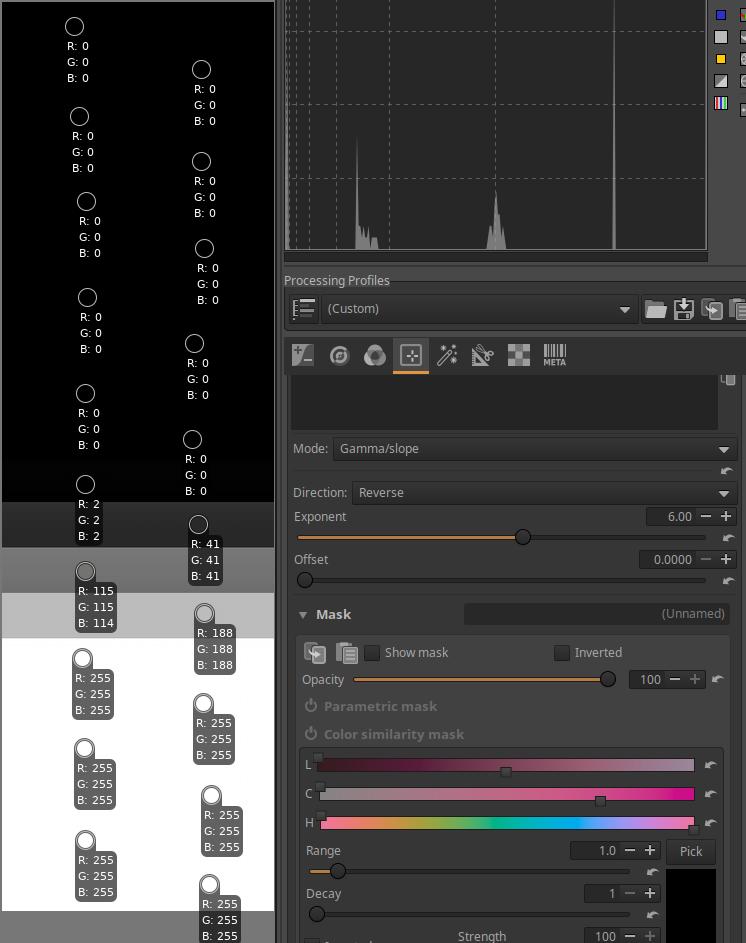

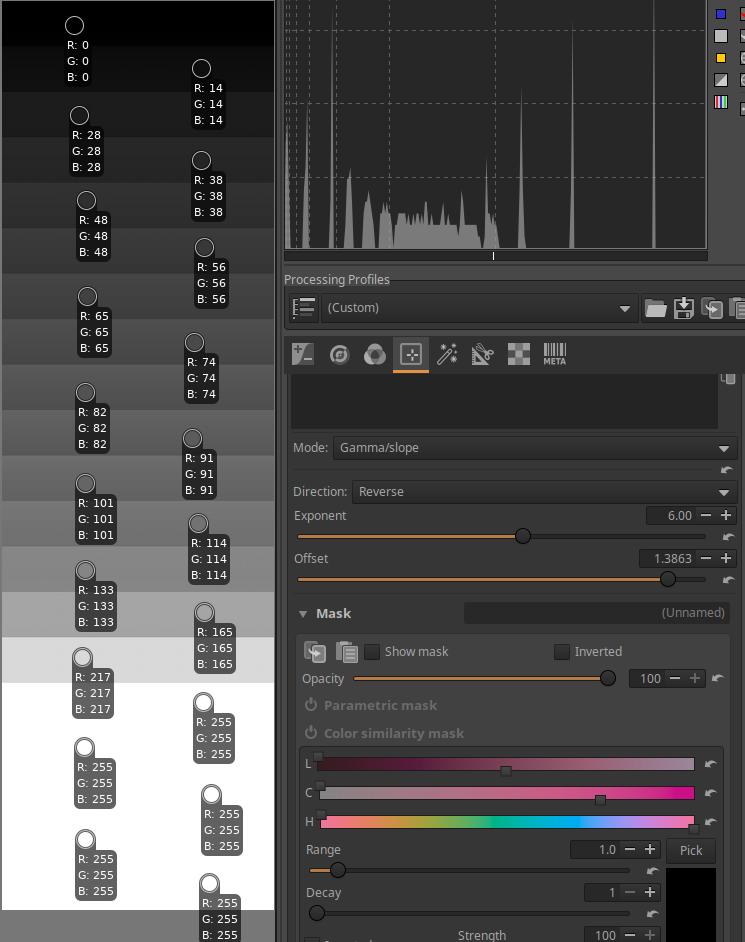

4.4.2.14 Gamma/slope CTL script

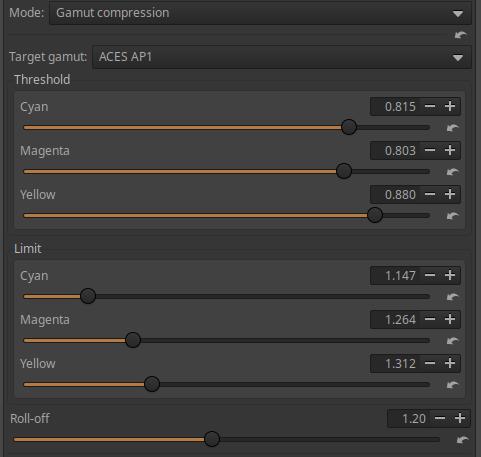

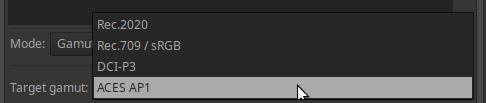

4.4.2.22 Gamut compression CTL script

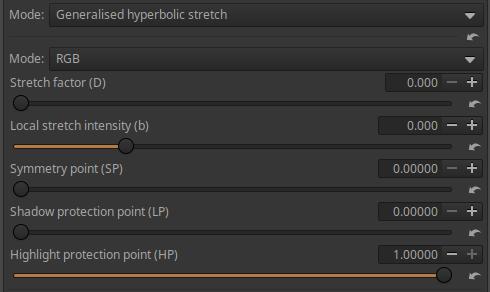

4.4.2.5 Generalised hyperbolic stretch CTL script

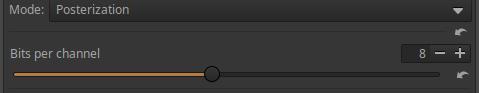

4.4.2.18 Posterization CTL script

4.4.2.6 Shadows lifting CTL script

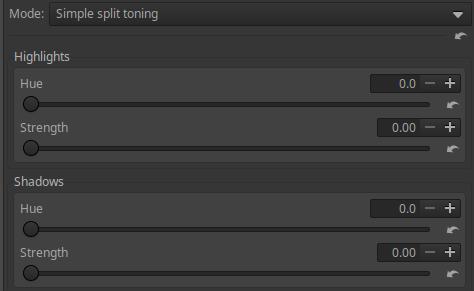

4.4.2.9 Simple split toning CTL script

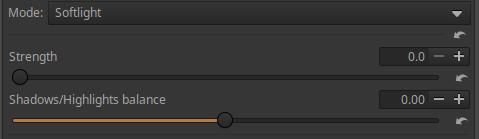

4.4.2.17 Softlight CTL script

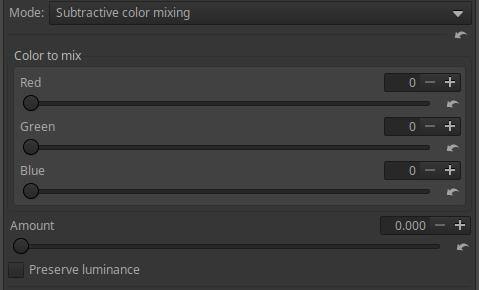

4.4.2.16 Subtractive color mixing CTL script

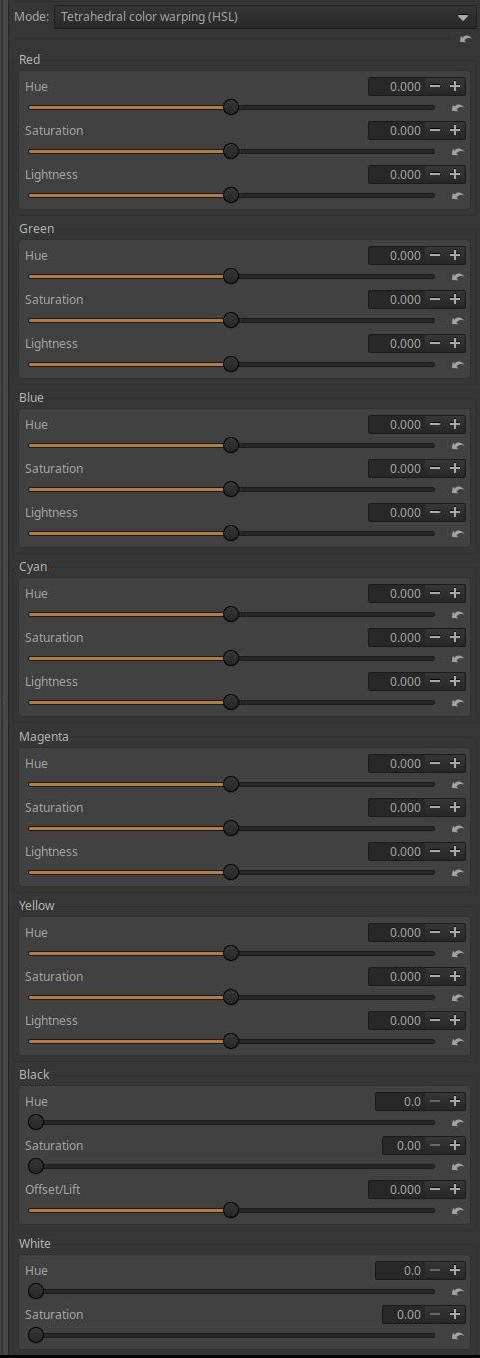

4.4.2.23 Tetrahedral color warping (HSL) CTL script

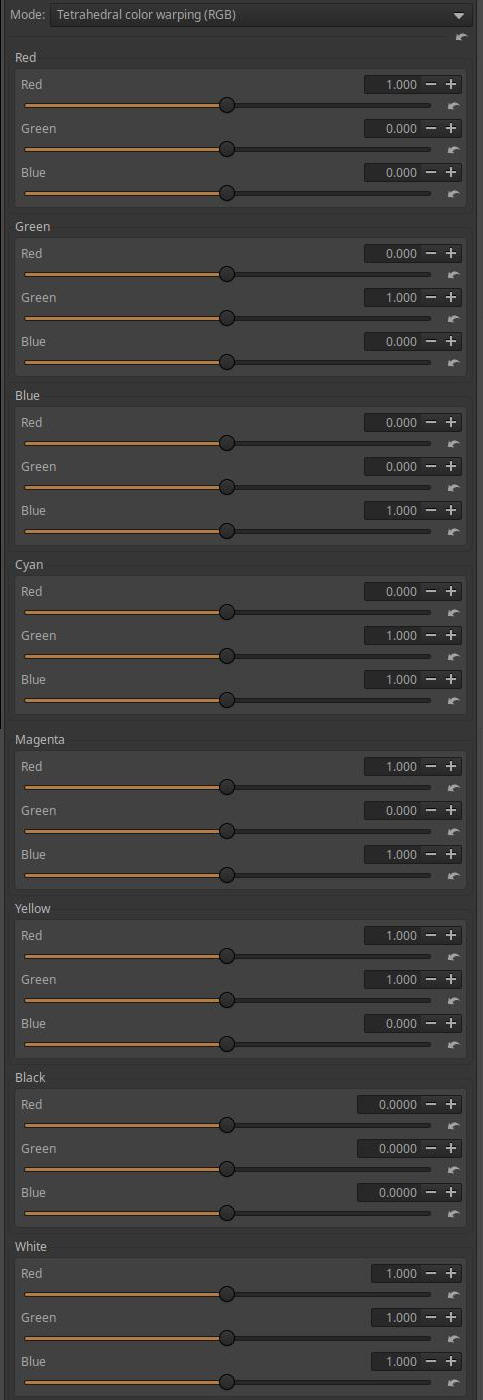

4.4.2.24 Tetrahedral color warping (RGB) CTL script

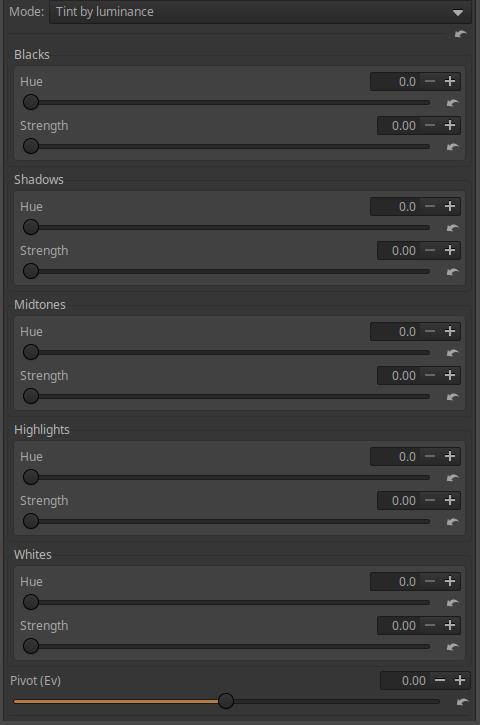

4.4.2.19 Tint by luminance CTL script

4.4.2.25 Tone curve CTL script

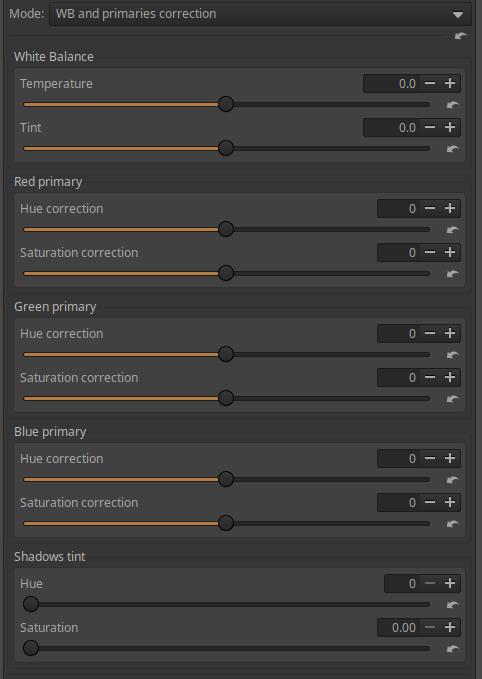

4.4.2.11 WB and primaries correction CTL script

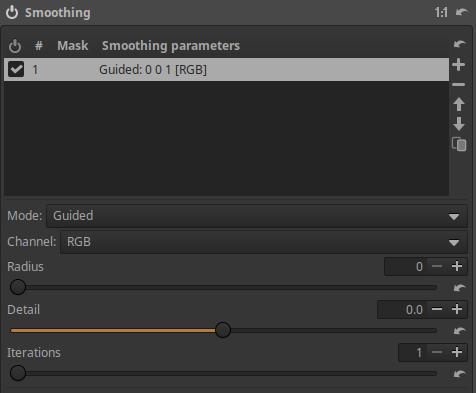

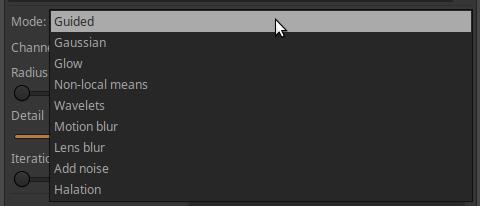

4.4.3 Smoothing

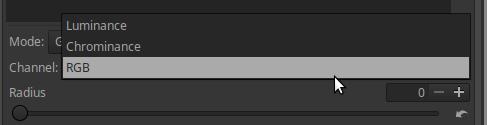

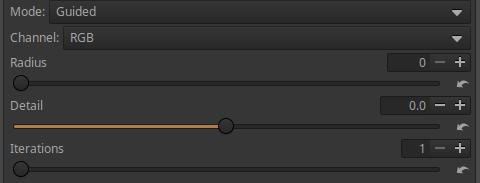

4.4.3.1 Guided

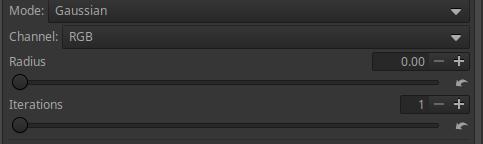

4.4.3.2 Gaussian

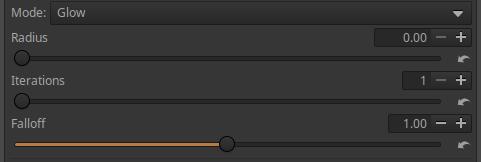

4.4.3.3 Glow

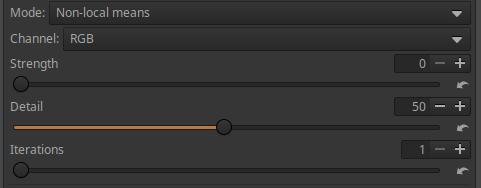

4.4.3.4 Non-local means

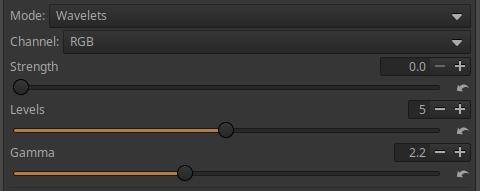

4.4.3.5 Wavelets

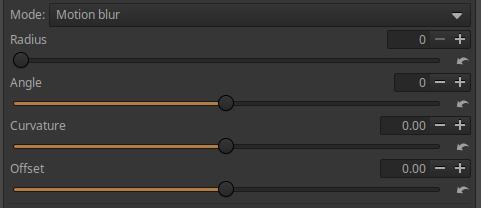

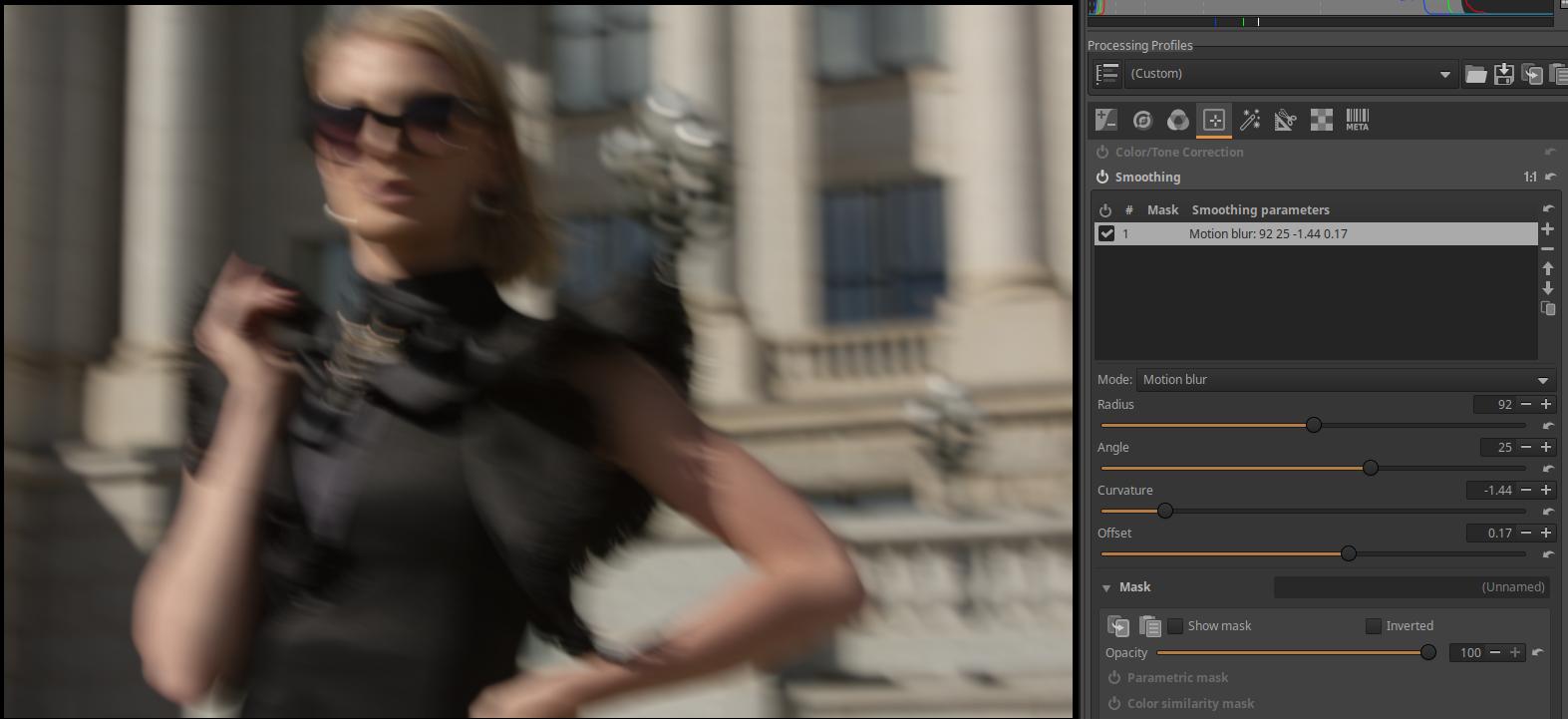

4.4.3.6 Motion blur

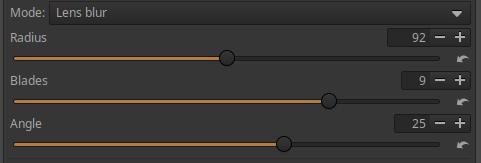

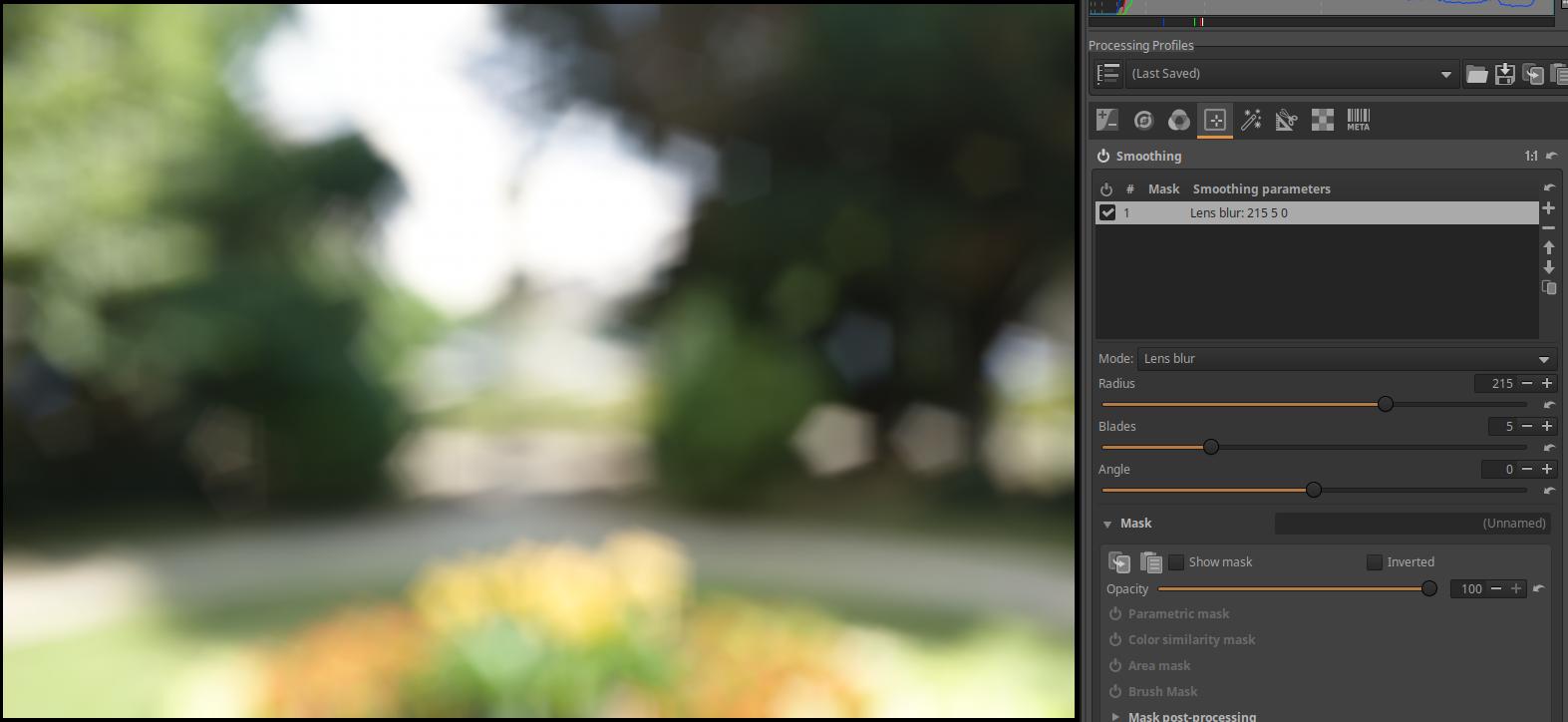

4.4.3.7 Lens blur

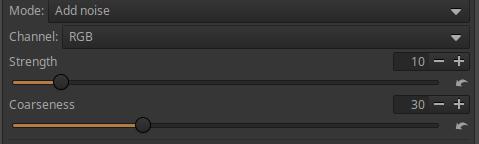

4.4.3.8 Add noise

4.4.3.9 Halation

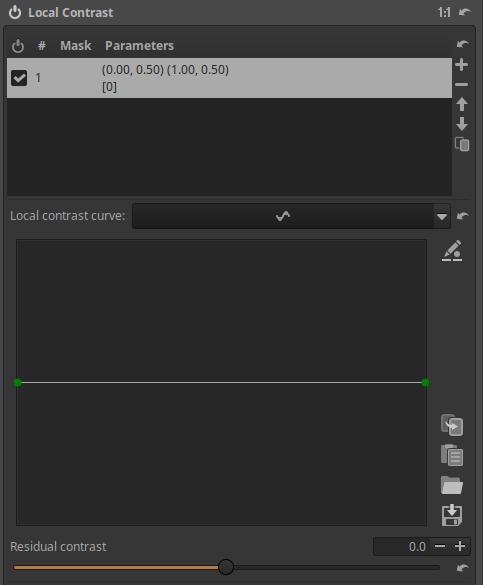

4.4.4 Local Contrast

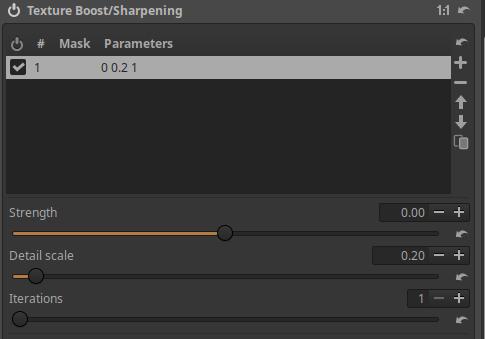

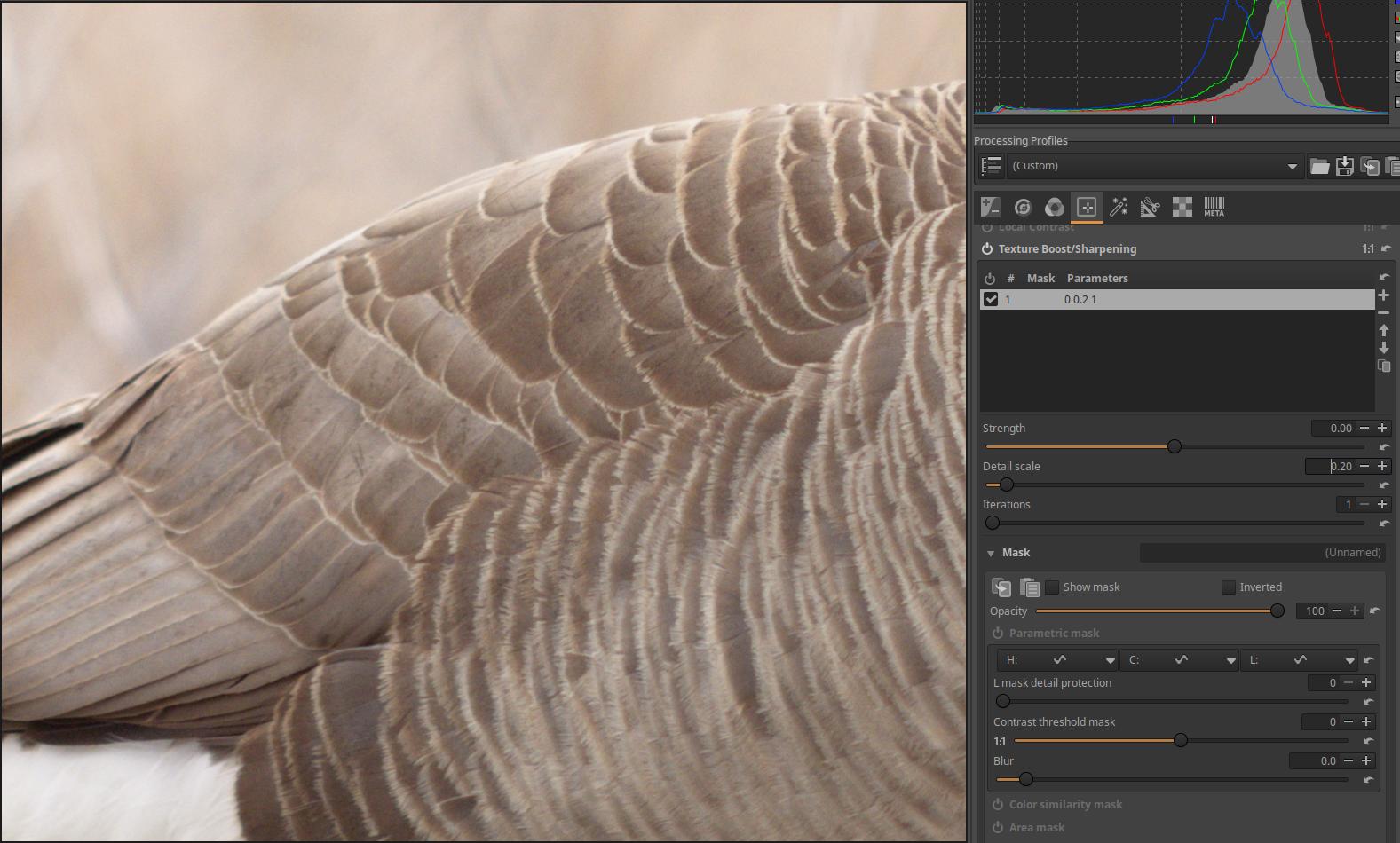

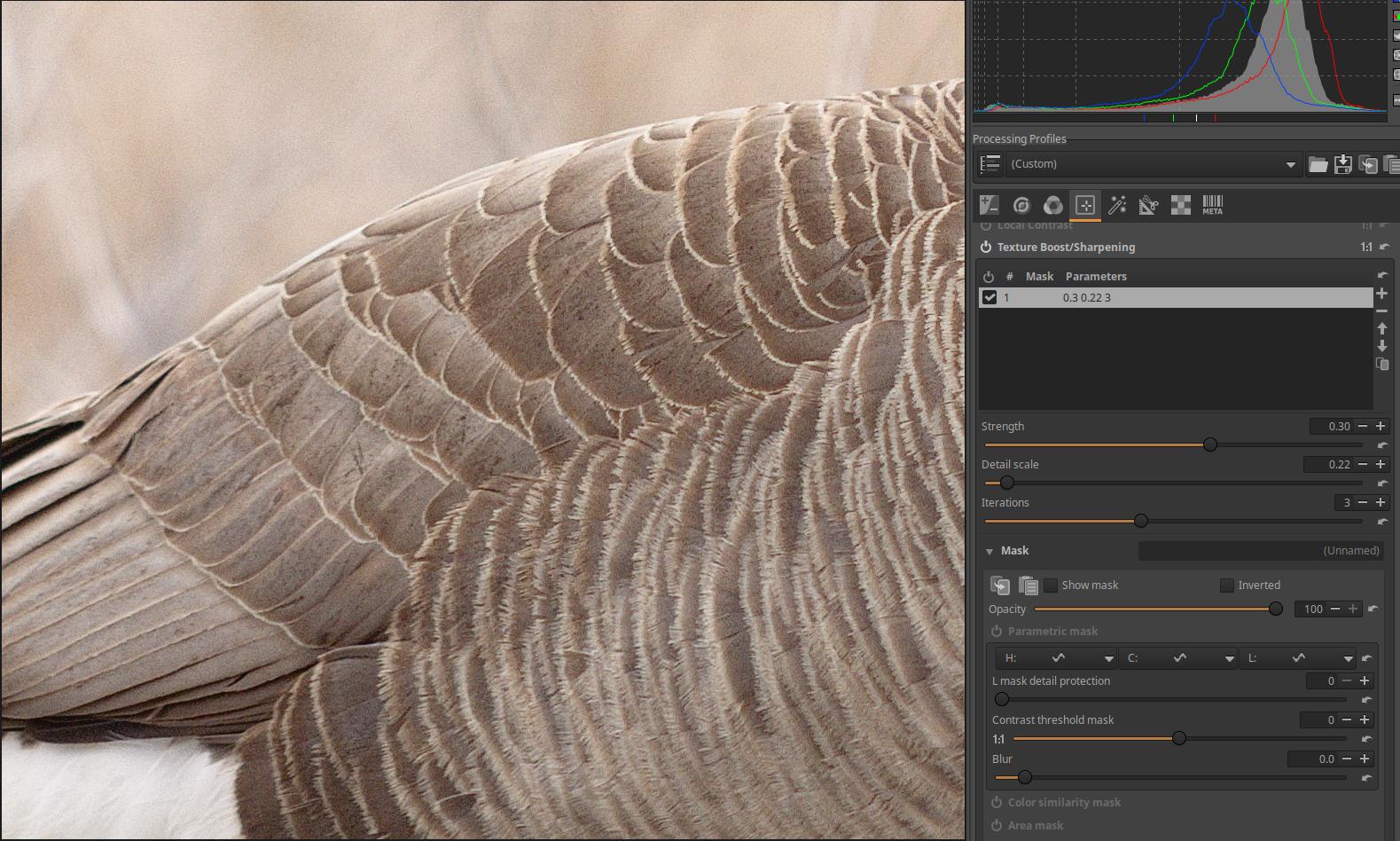

4.4.5 Texture Boost/Sharpening

4.5 Special effects group

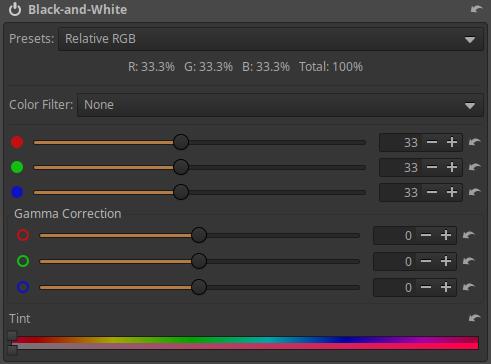

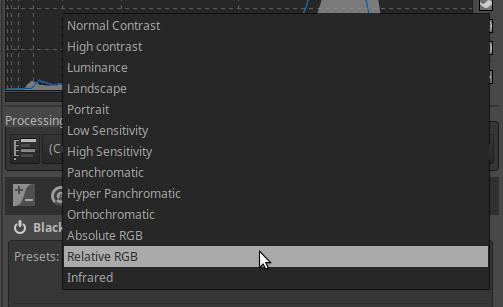

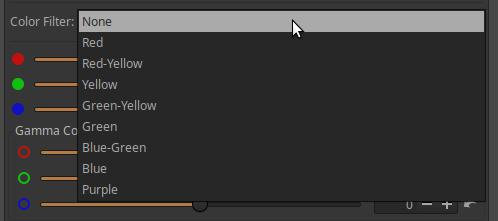

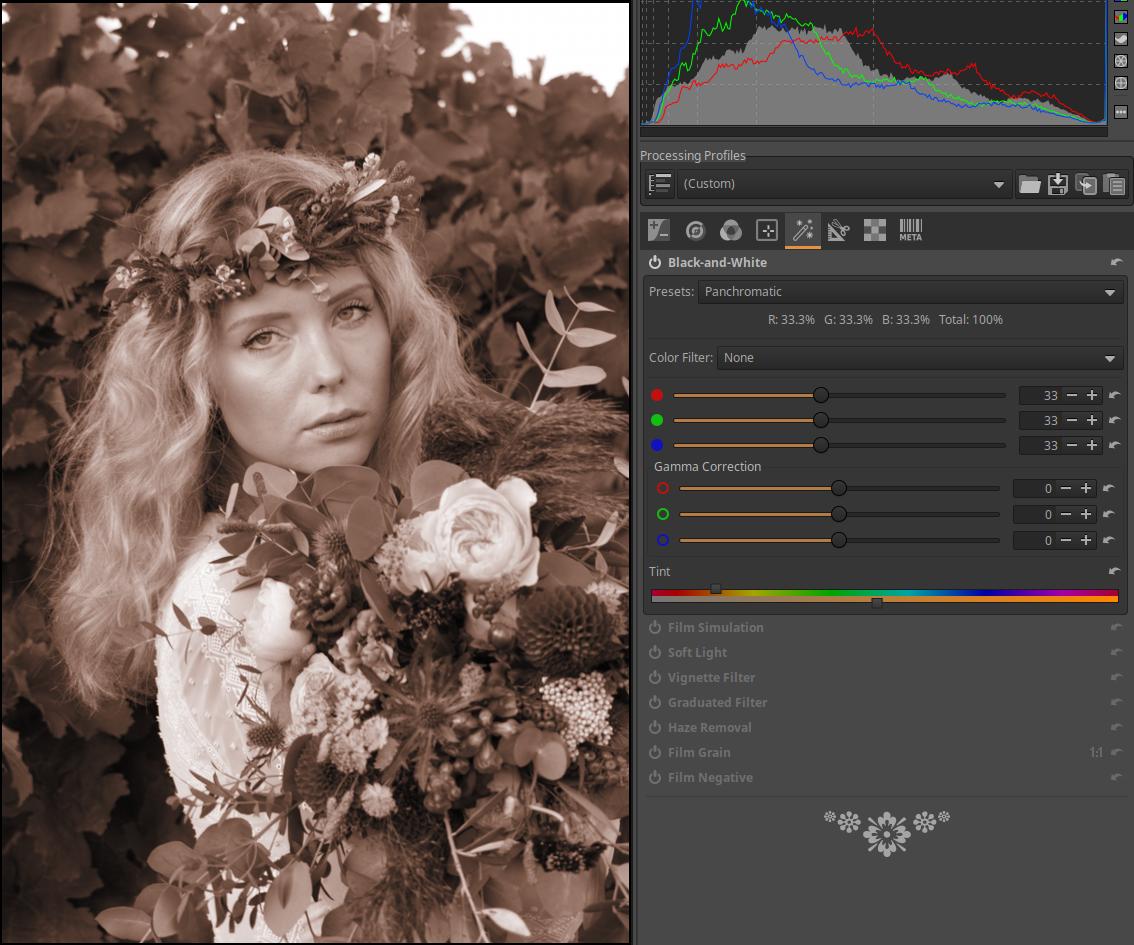

4.5.1 Black-and-White

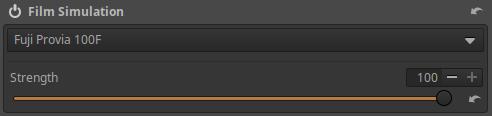

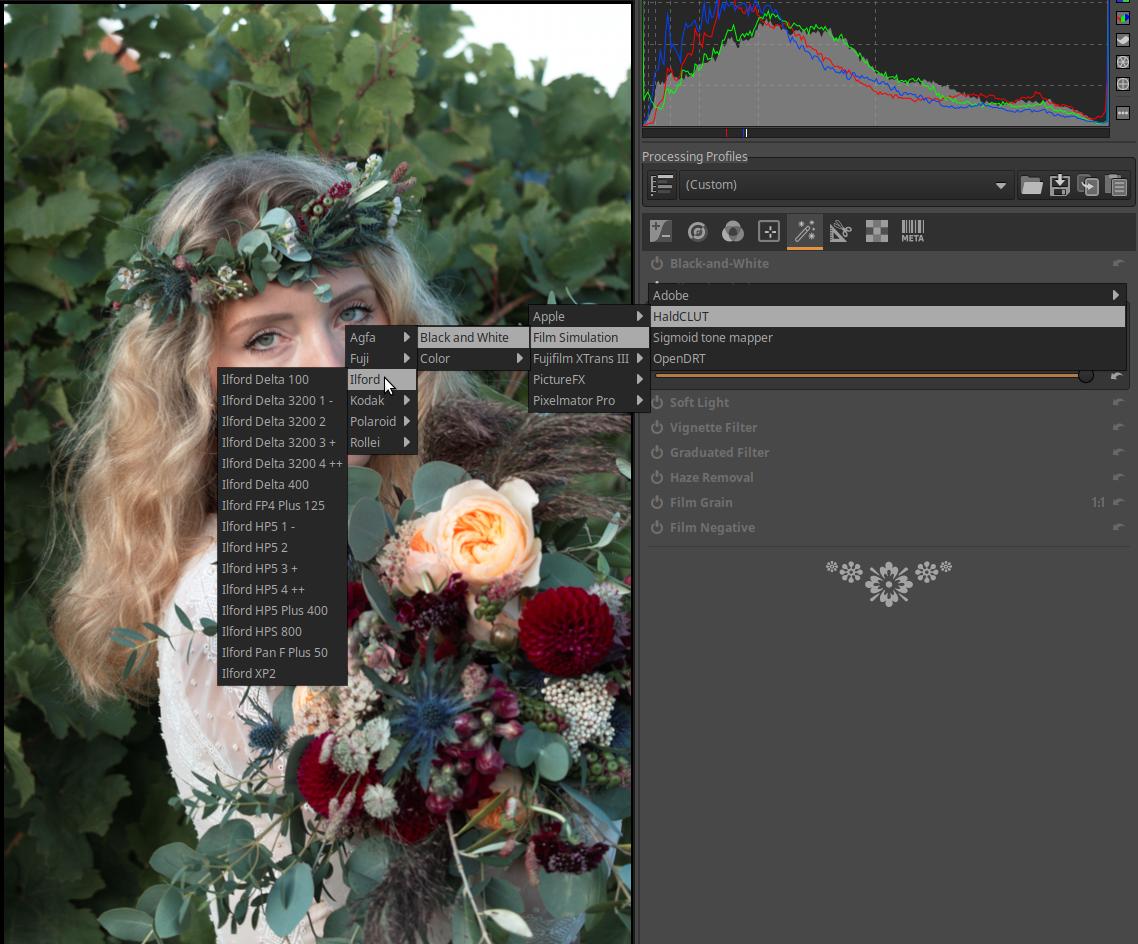

4.5.2 Film Simulation

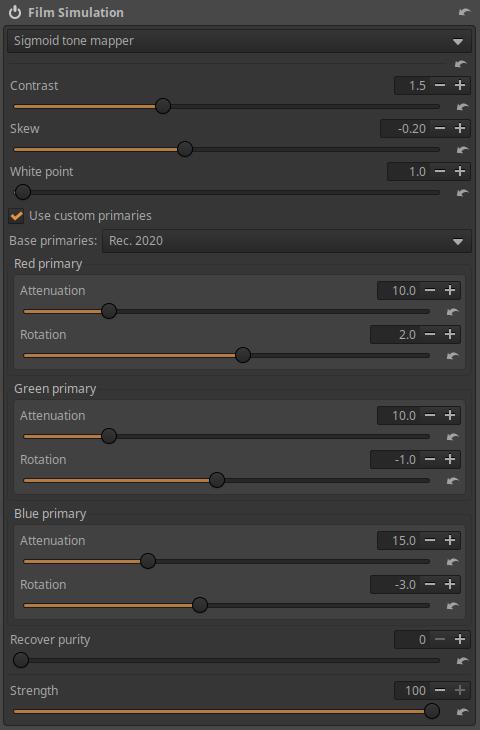

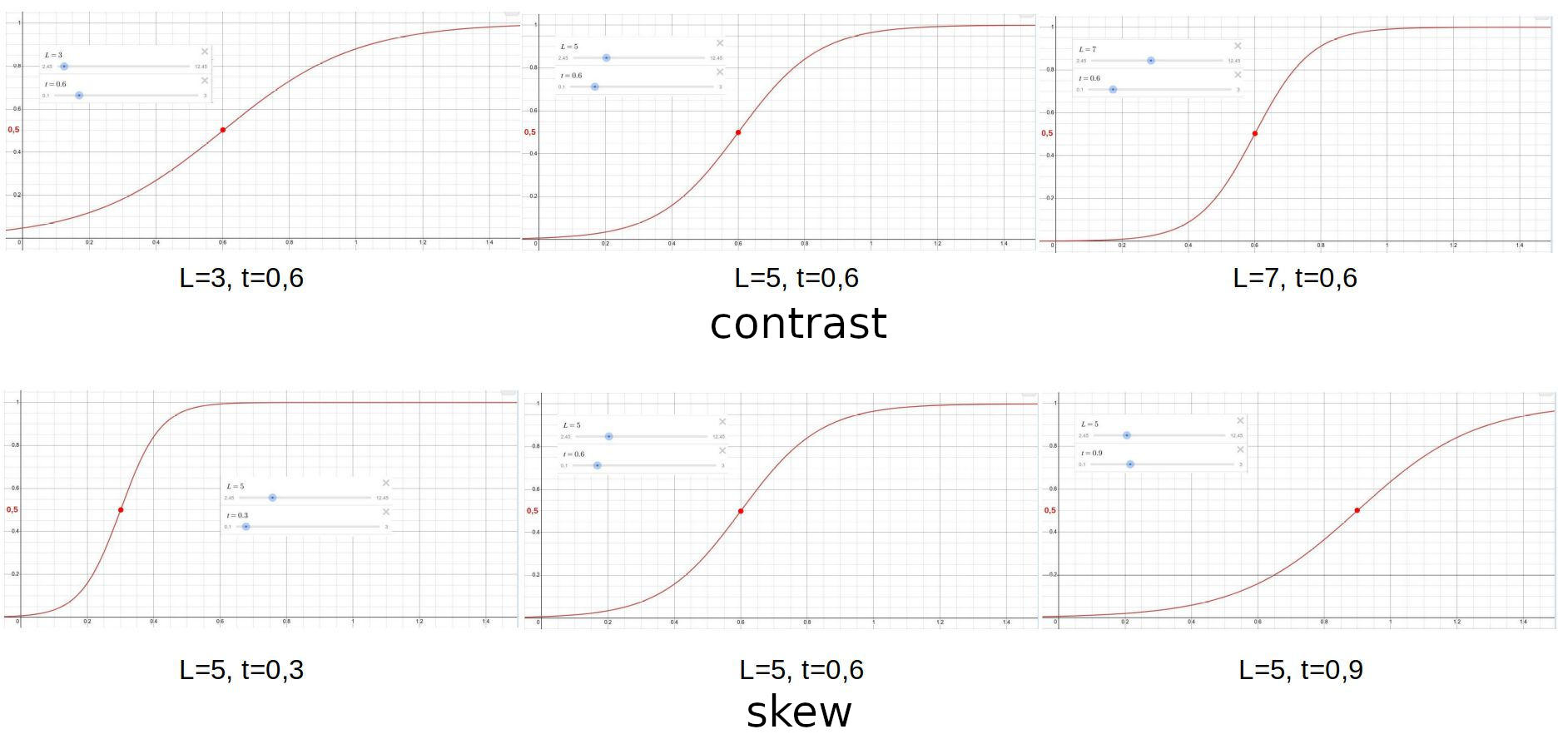

4.5.2.1 Sigmoid tone mapper

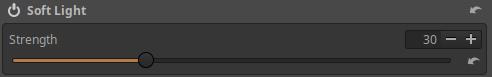

4.5.3 Soft Light

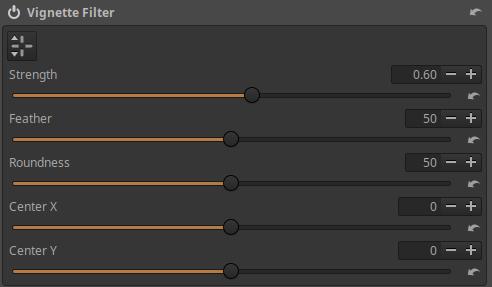

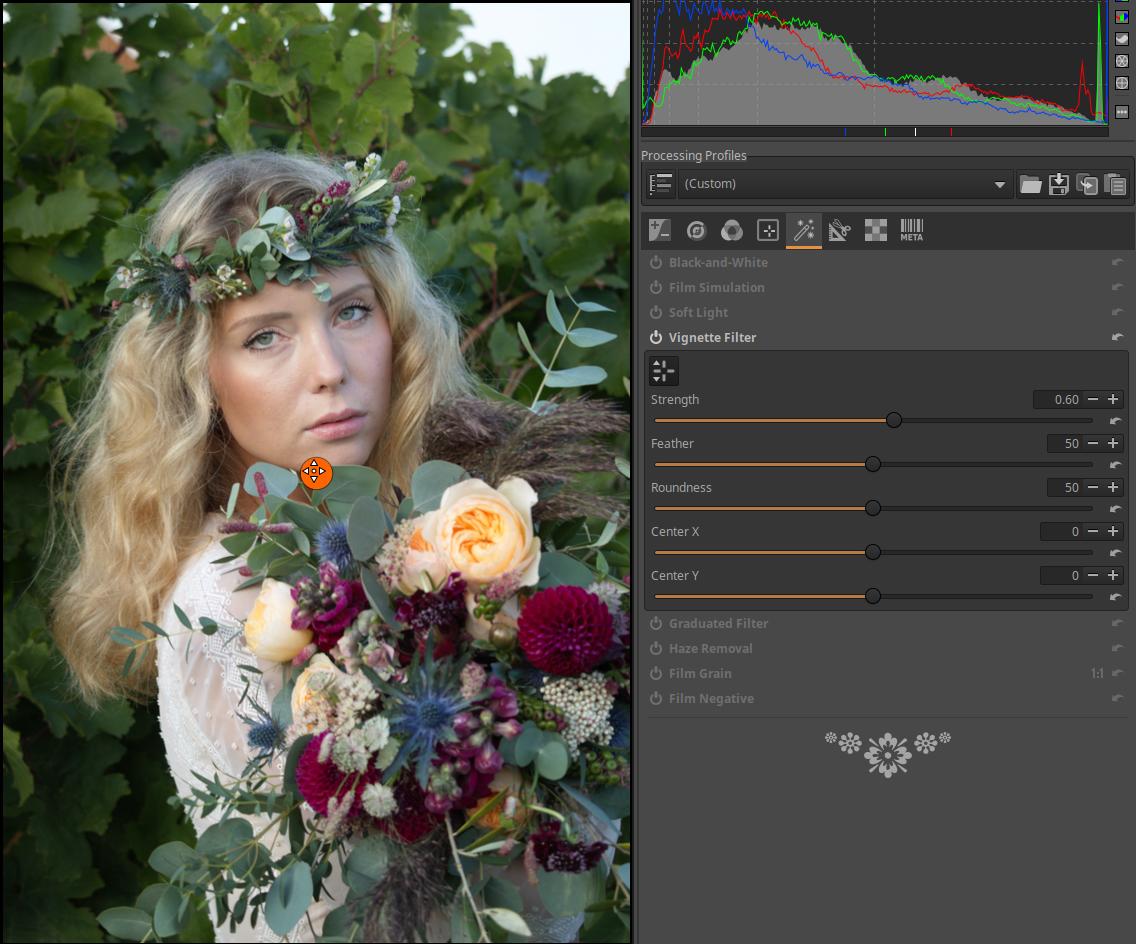

4.5.4 Vignette Filter

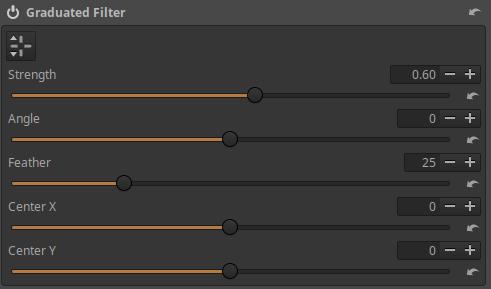

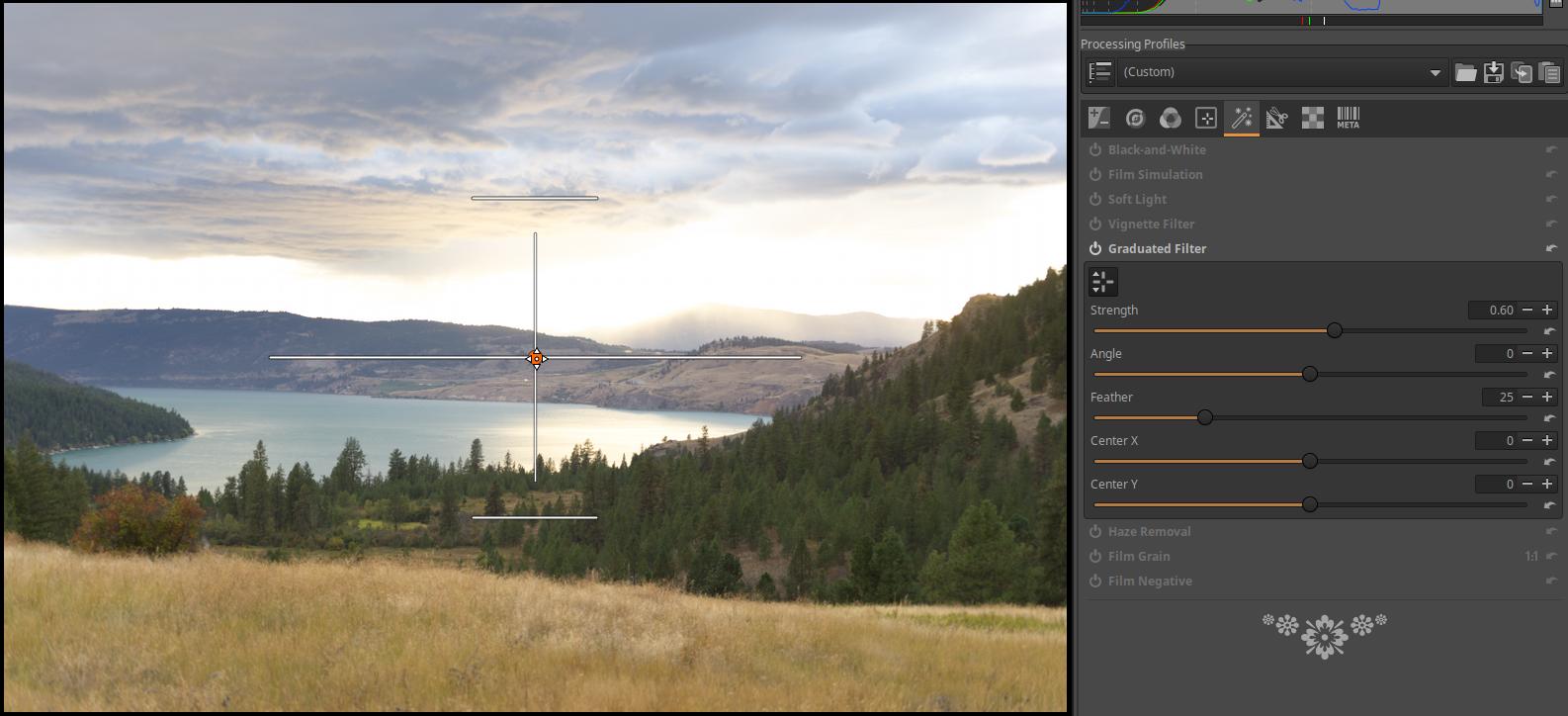

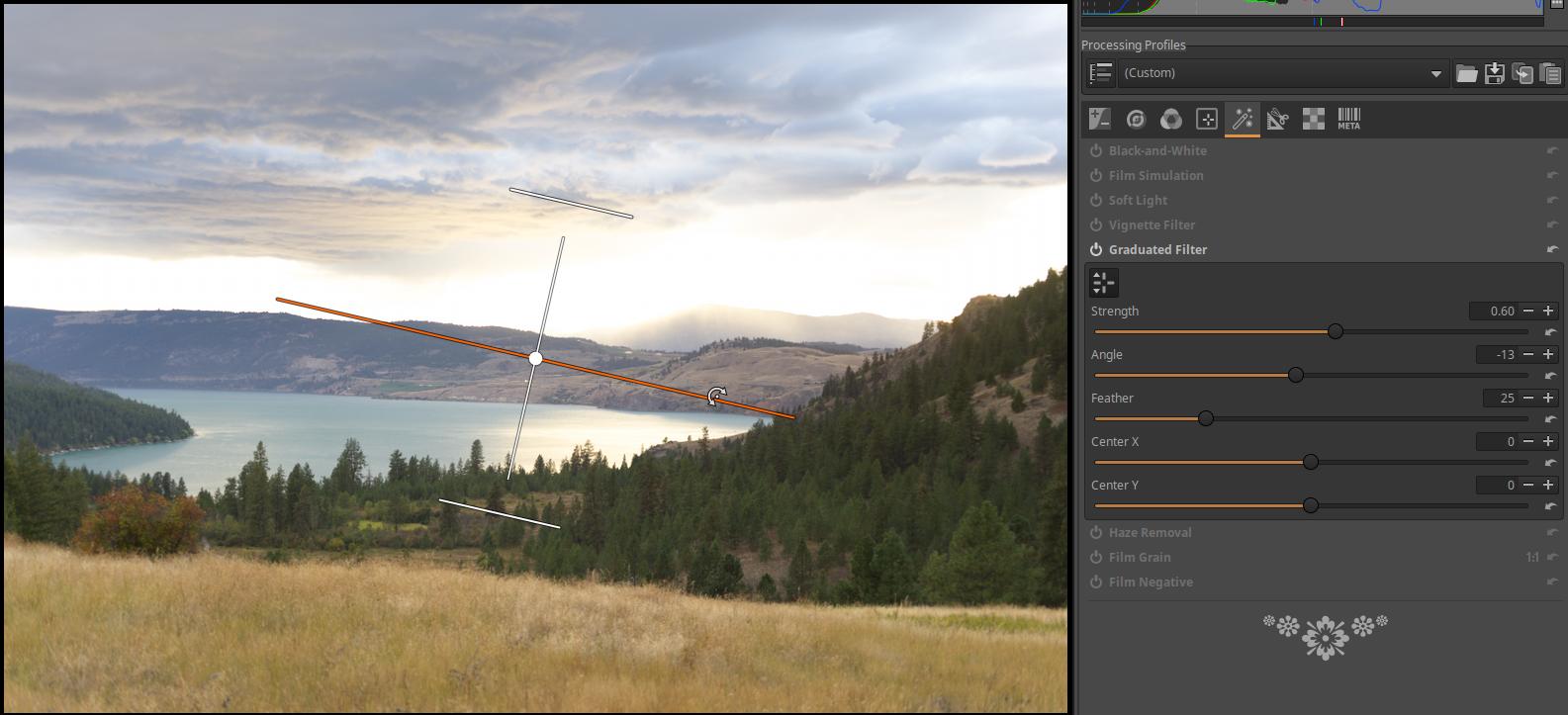

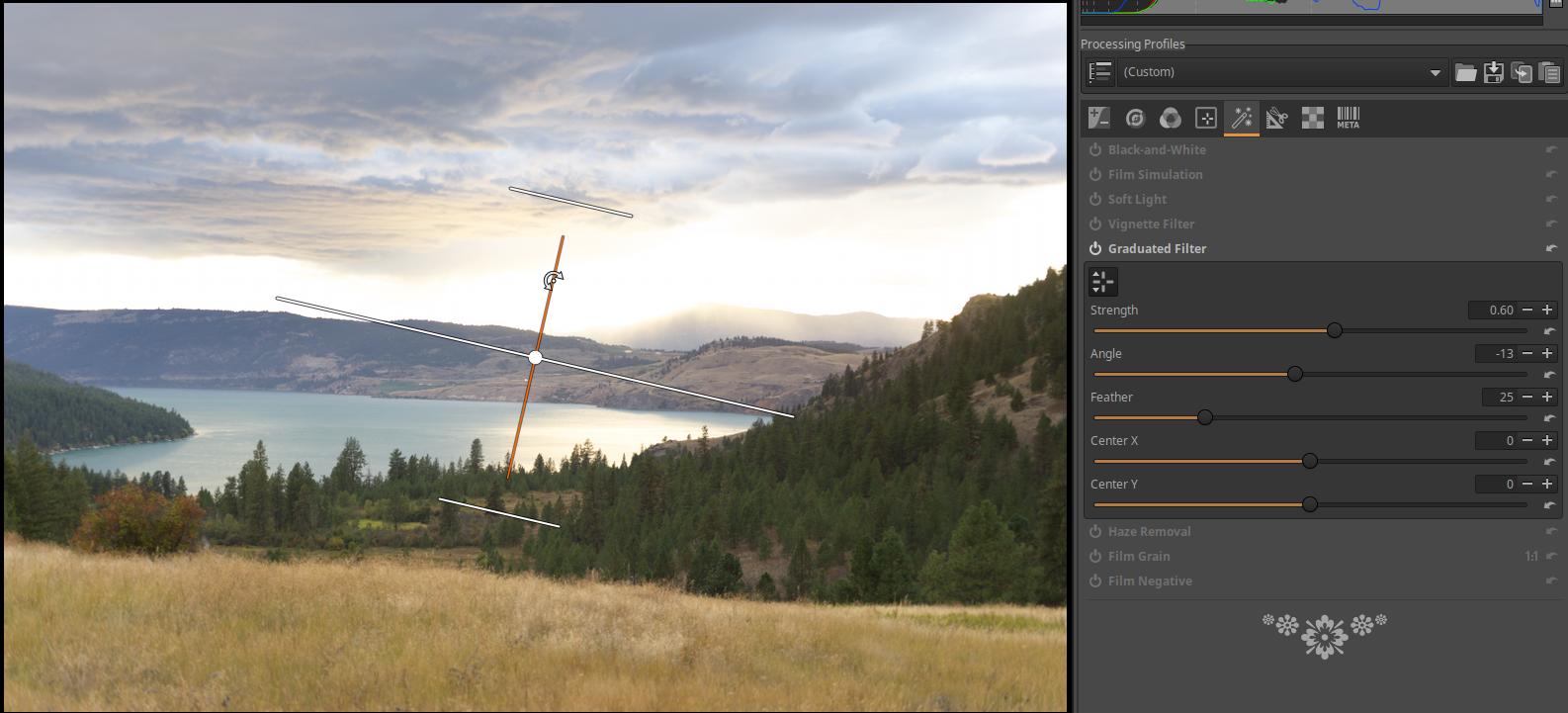

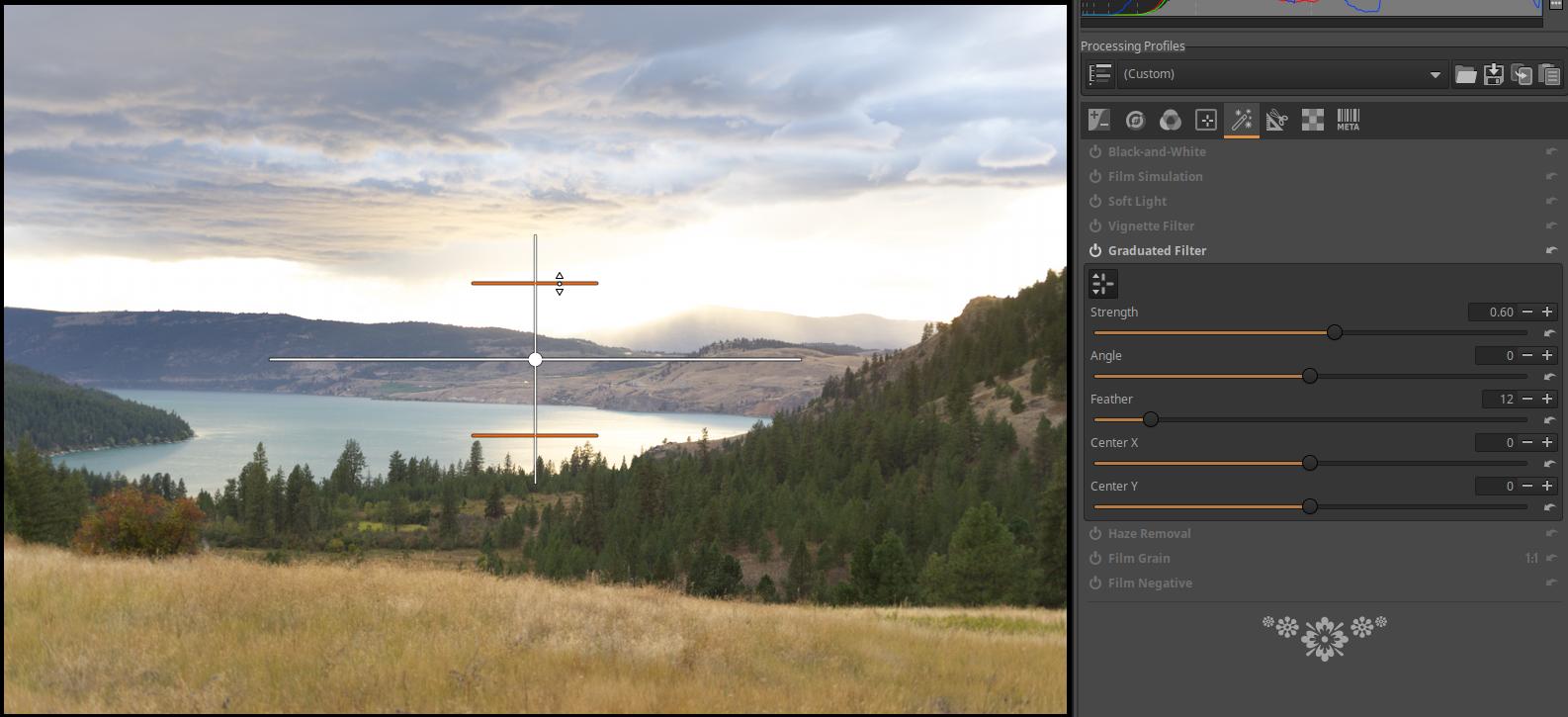

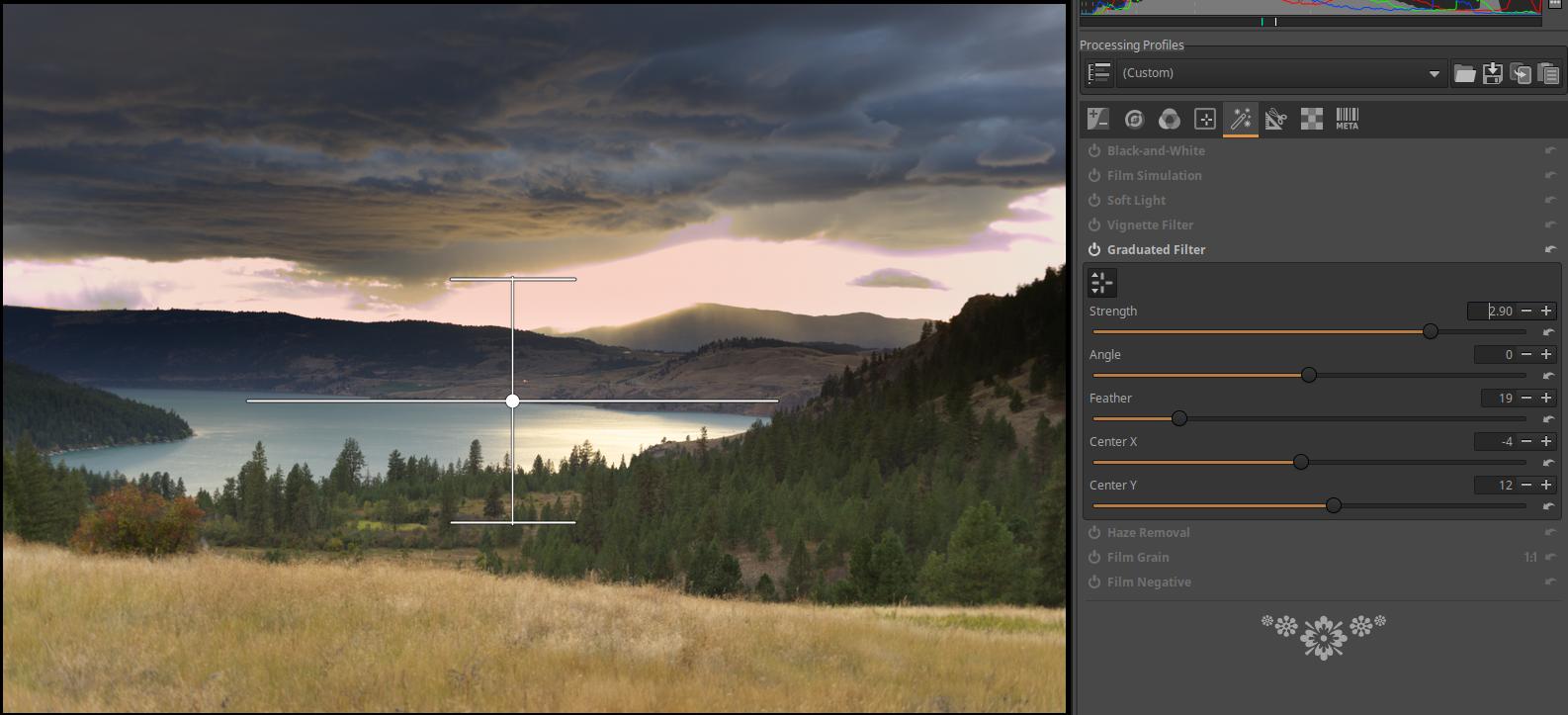

4.5.5 Graduated Filter

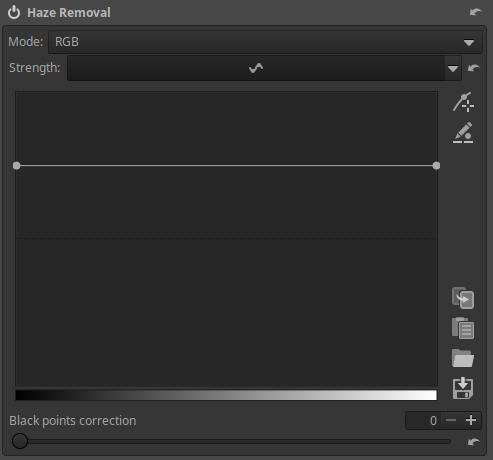

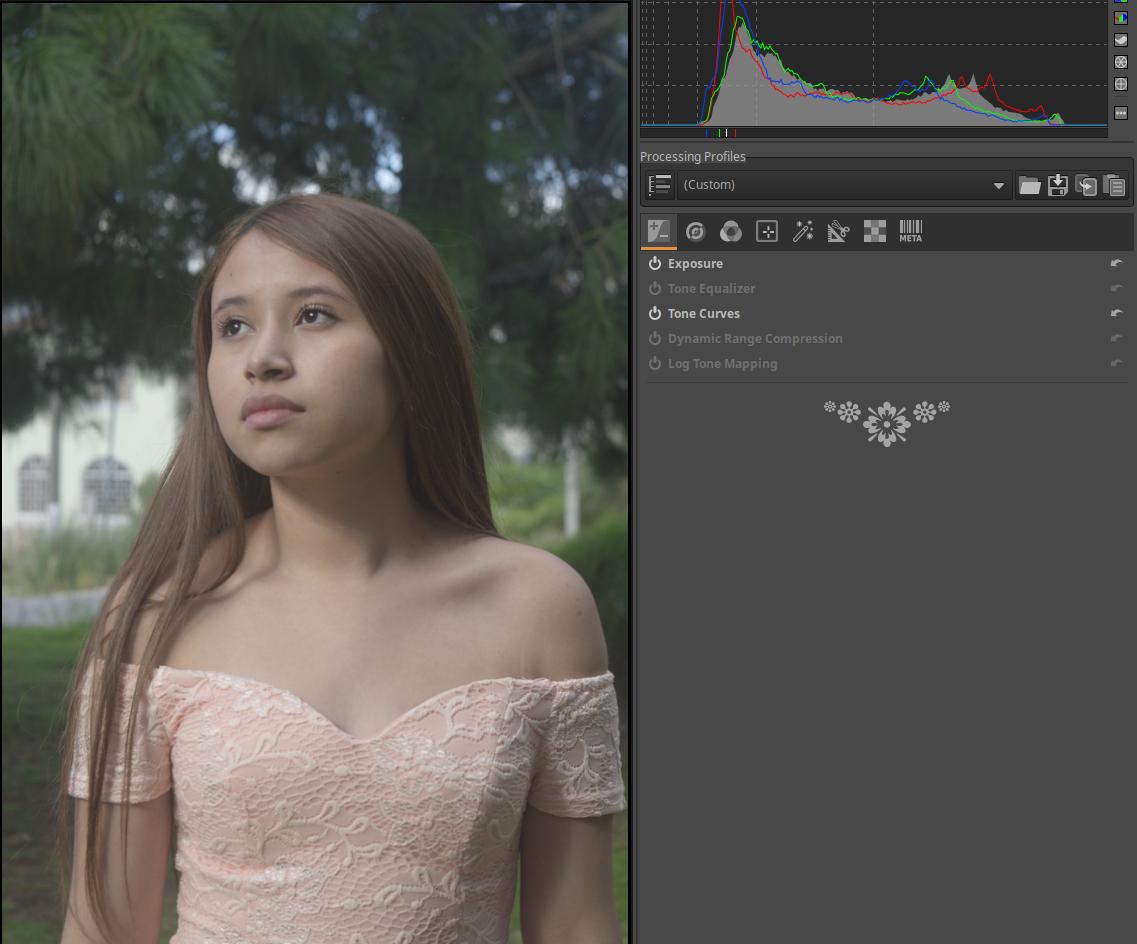

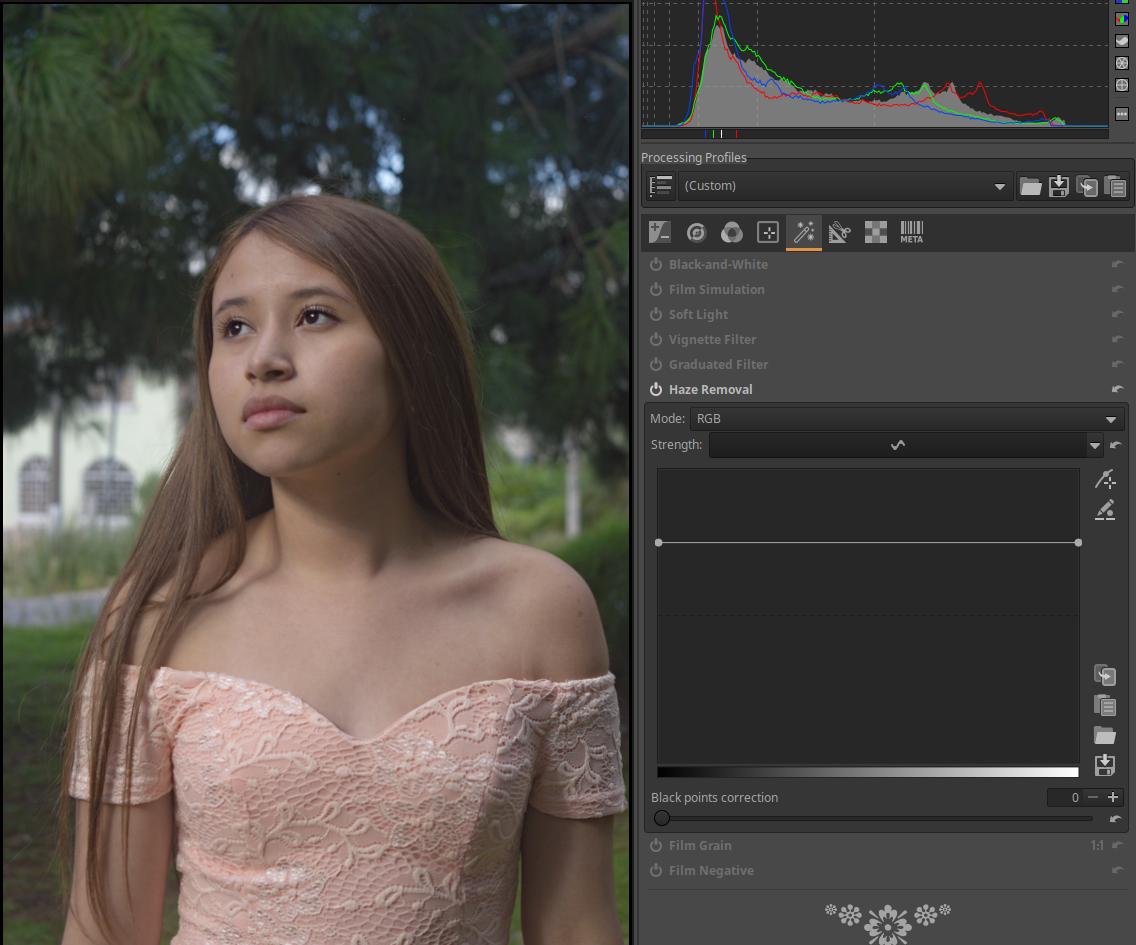

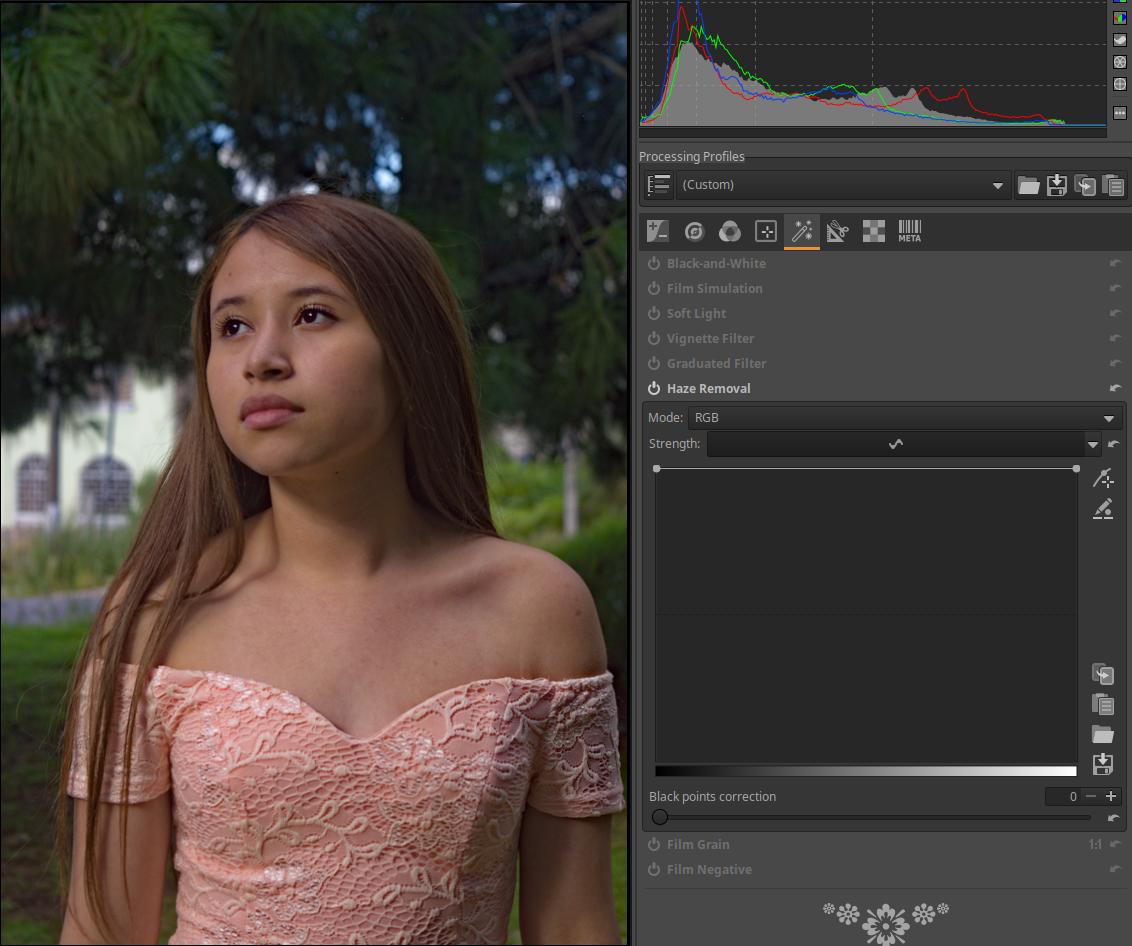

4.5.6 Haze Removal

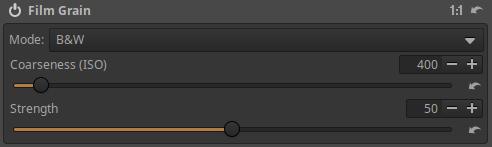

4.5.7 Film Grain

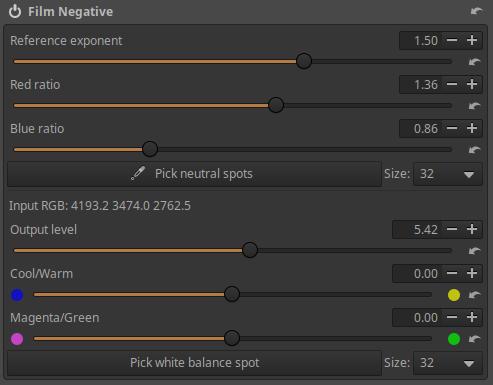

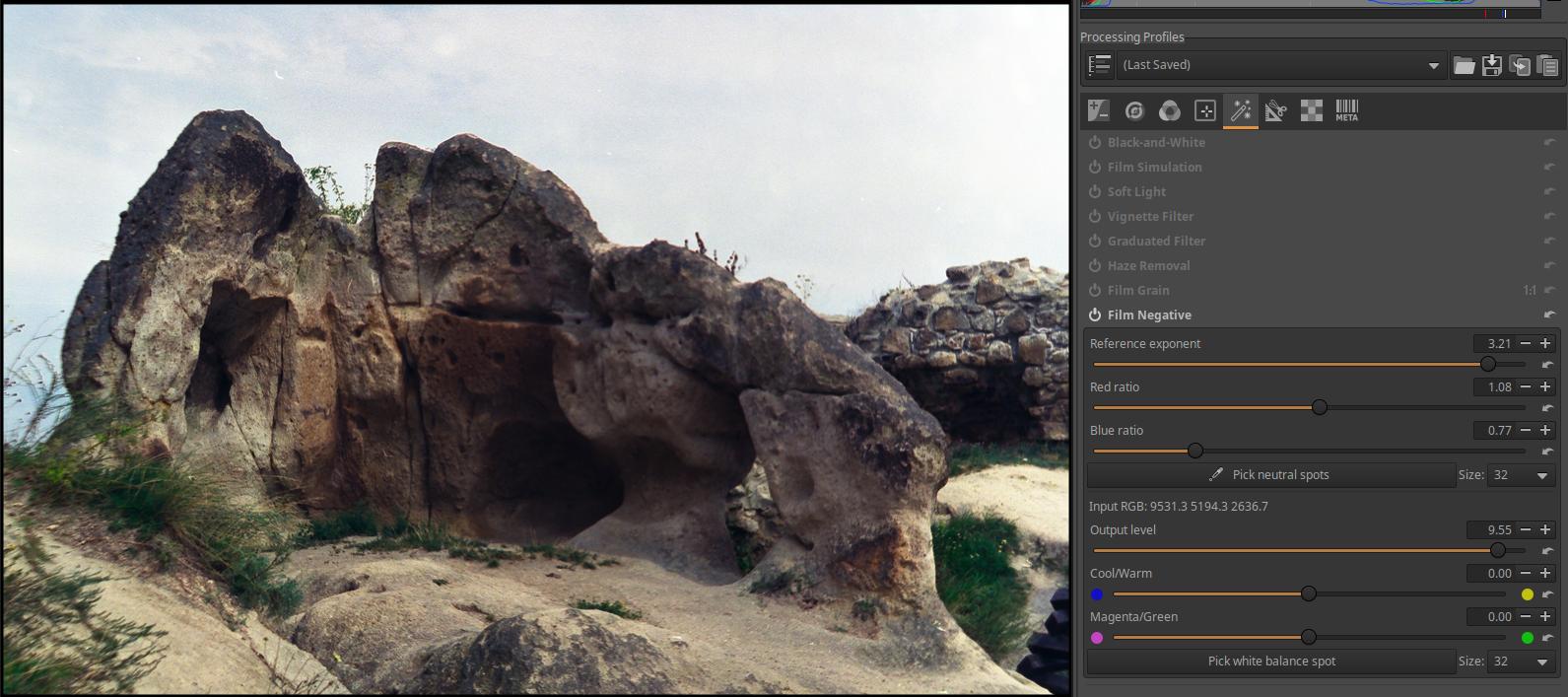

4.5.8 Film Negative

4.6 Transform group

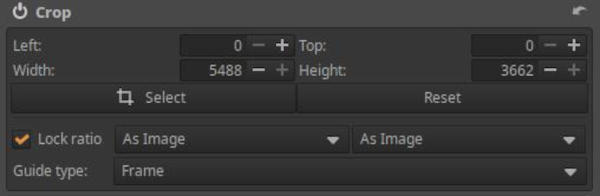

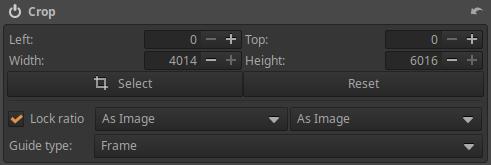

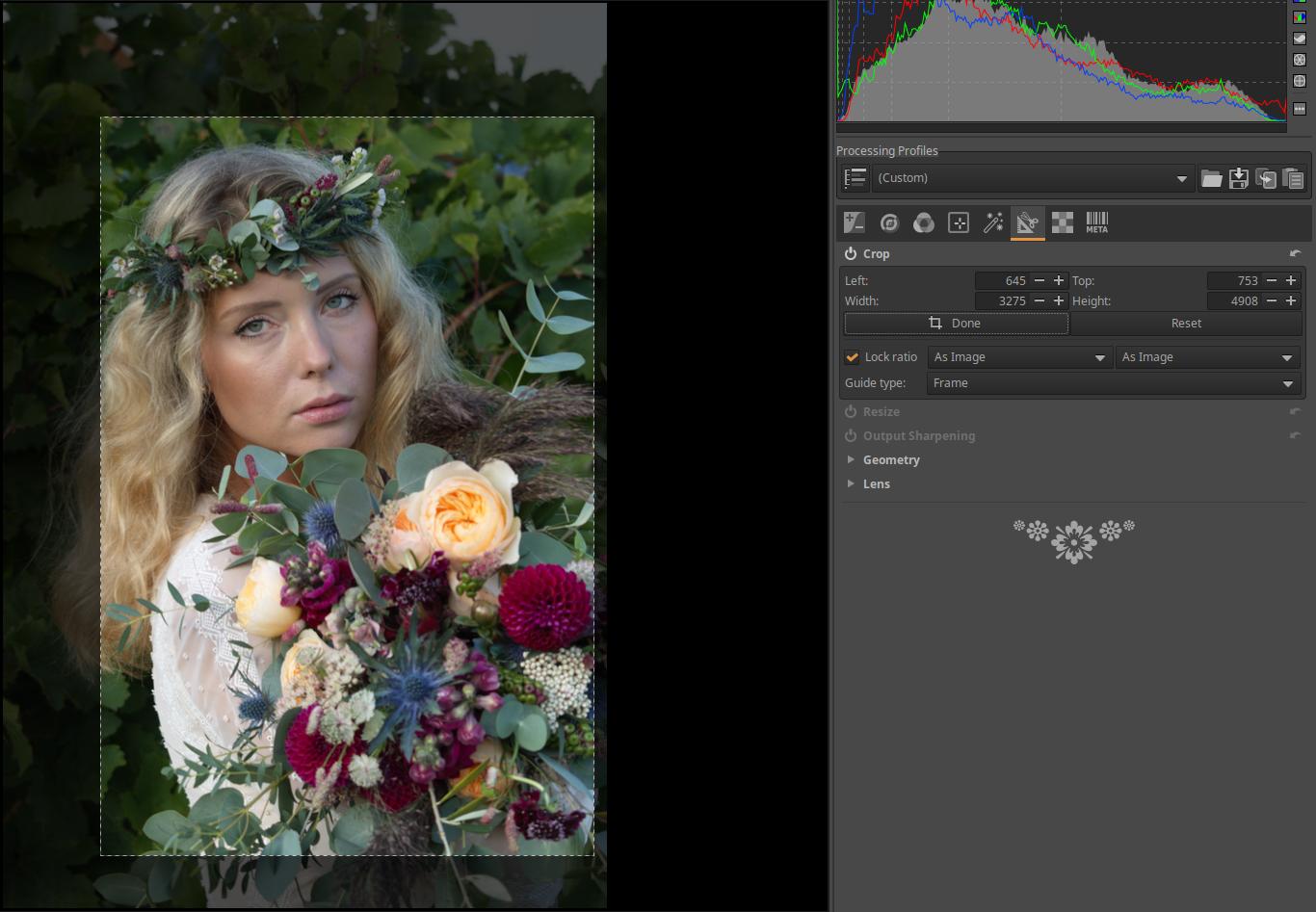

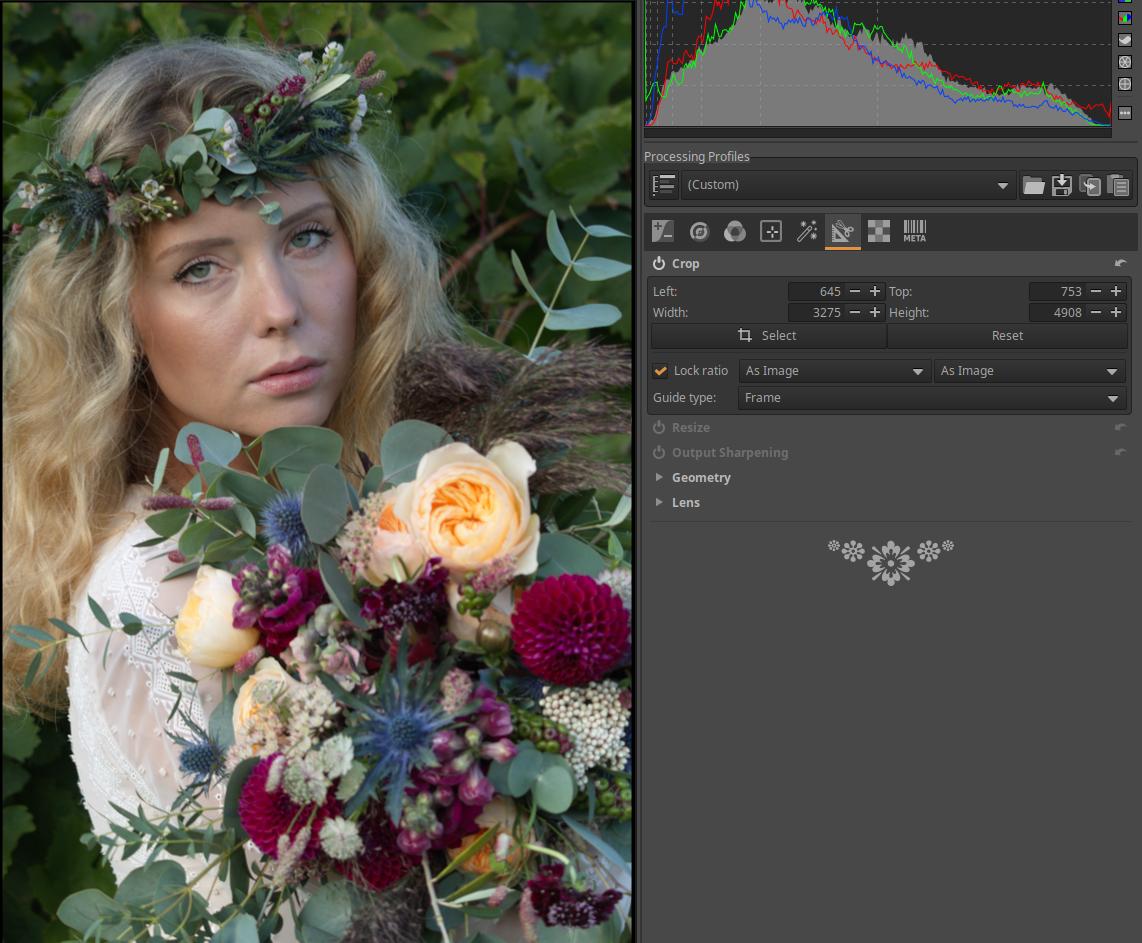

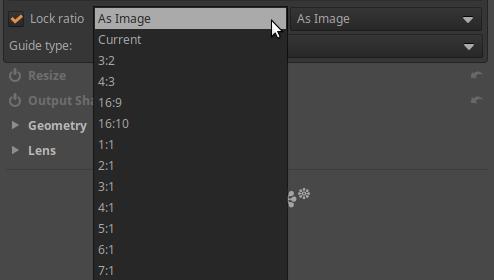

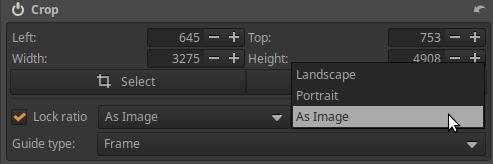

4.6.1 Crop

4.6.2 Resize

4.6.3 Output Sharpening

4.6.4 Geometry subgroup

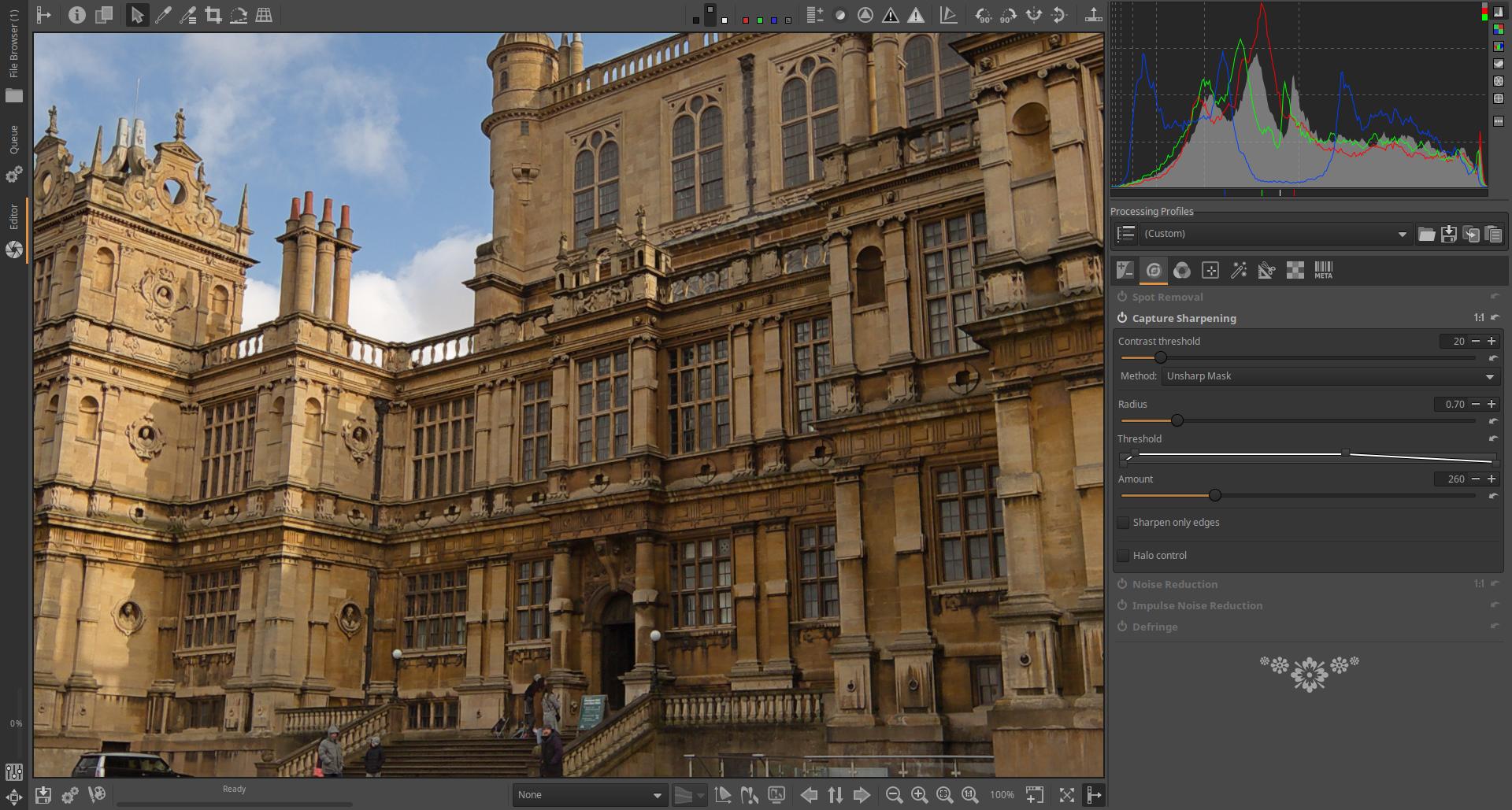

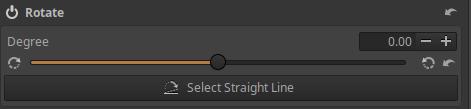

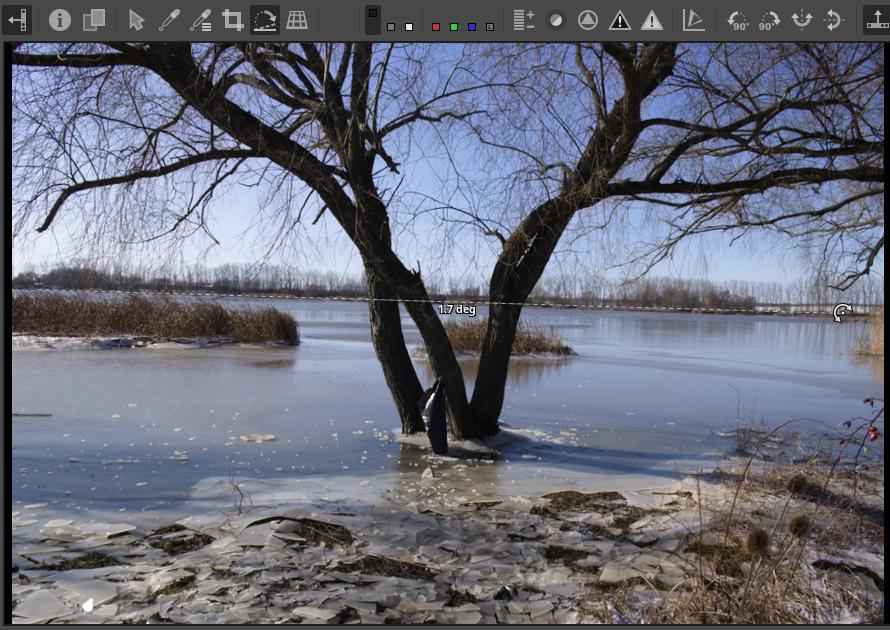

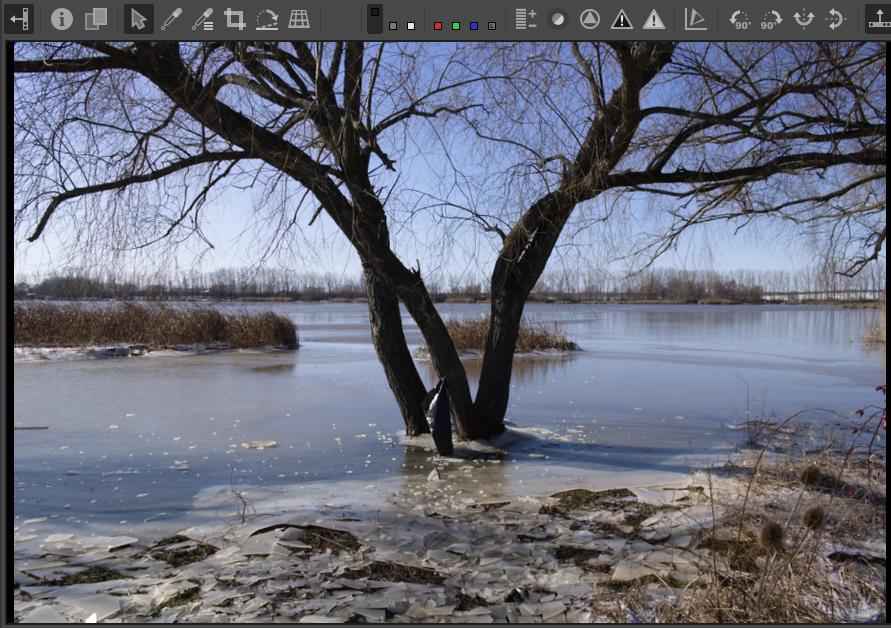

4.6.4.1 Rotate

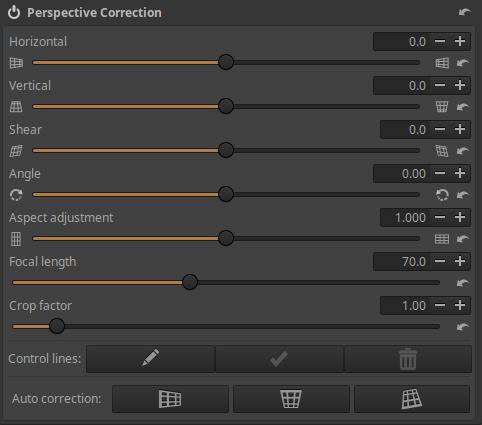

4.6.4.2 Perspective Correction

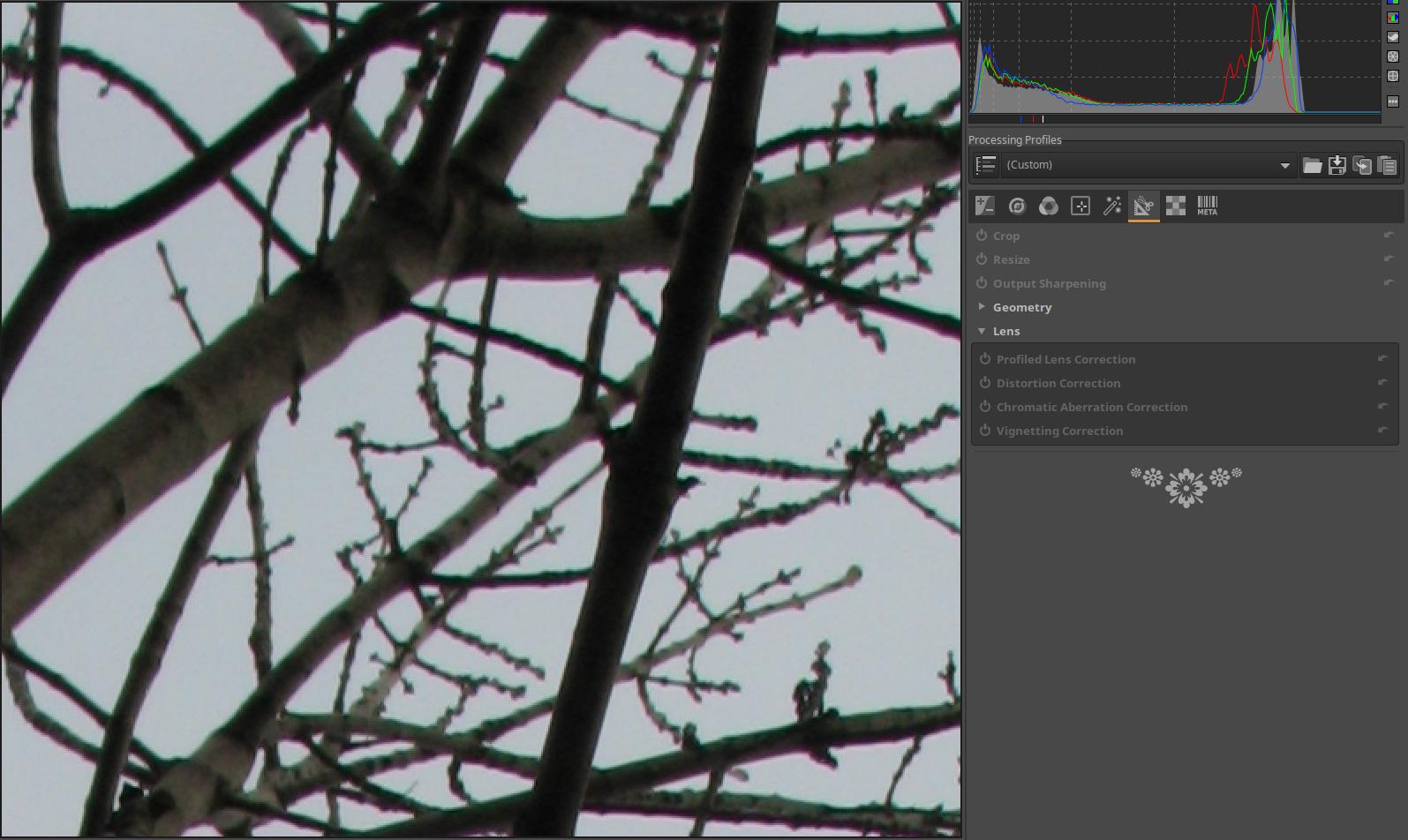

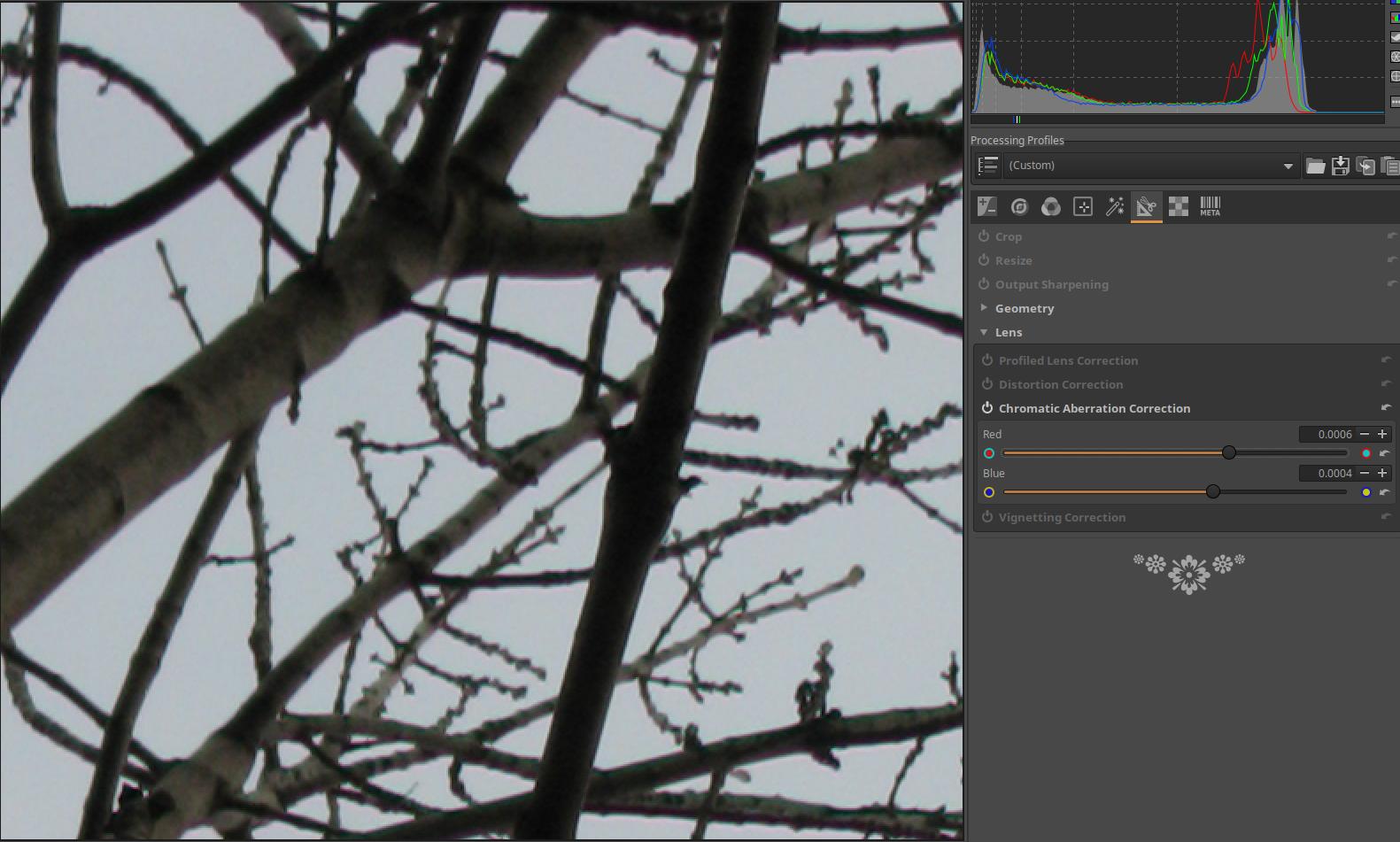

4.6.5 Lens subgroup

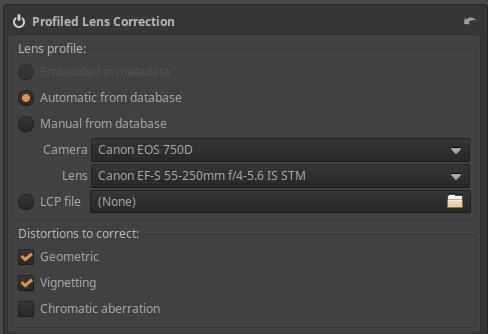

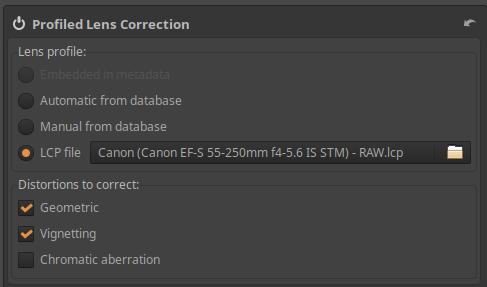

4.6.5.1 Profiled Lens Correction

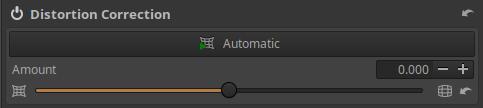

4.6.5.2 Distortion Correction

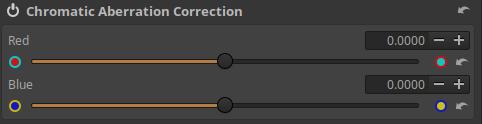

4.6.5.3 Chromatic Aberration Correction

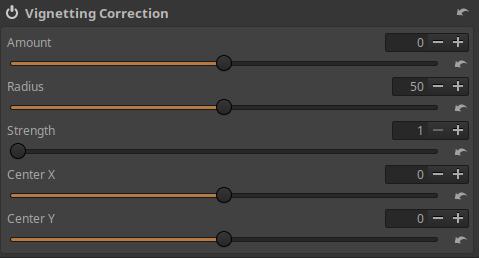

4.6.5.4 Vignetting Correction

4.7 Raw group

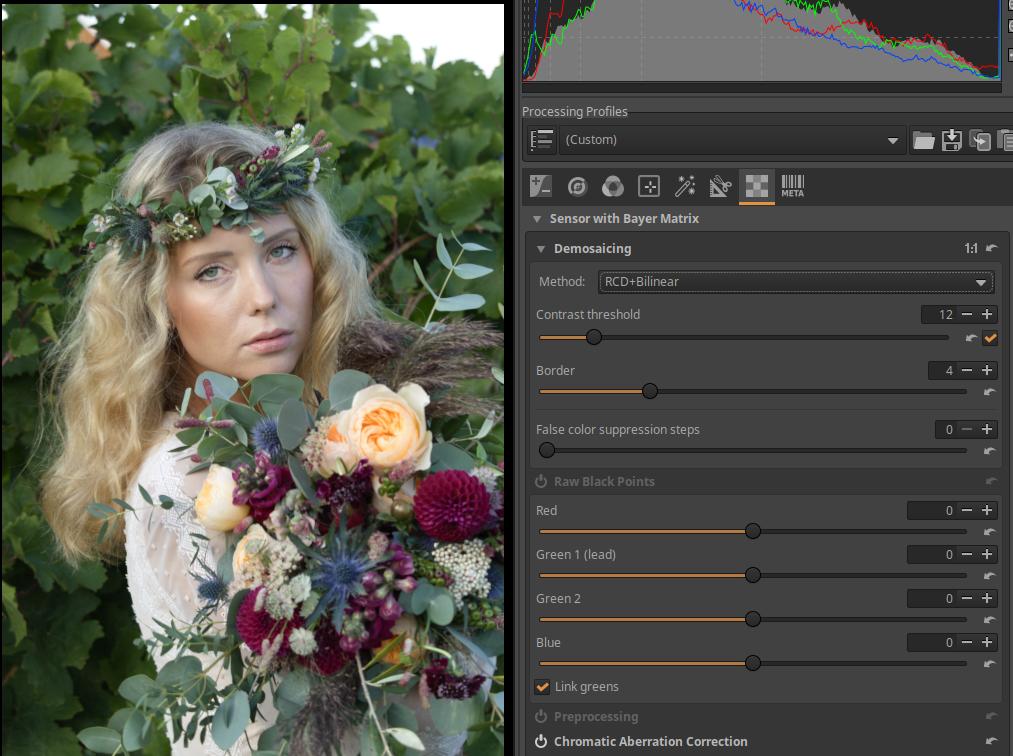

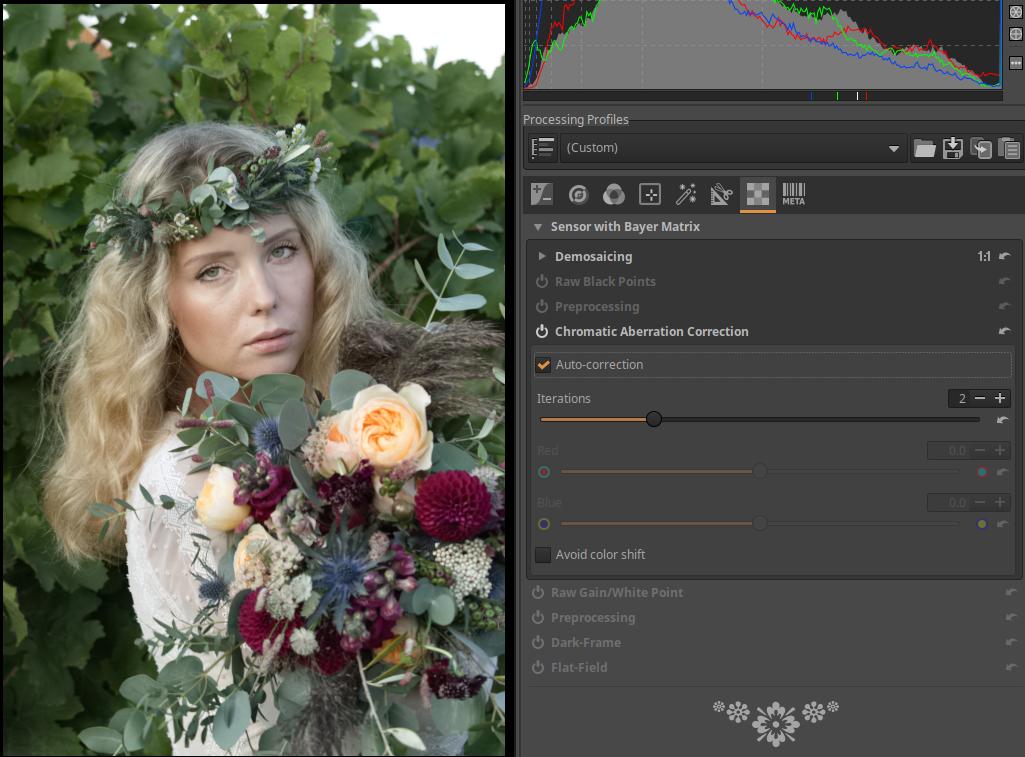

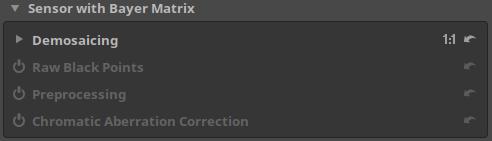

4.7.1 Sensor with Bayer Matrix subgroup

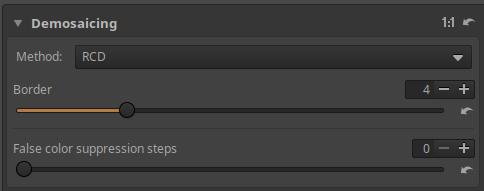

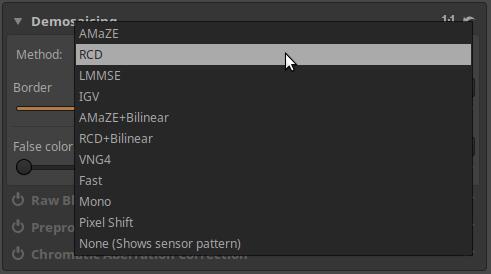

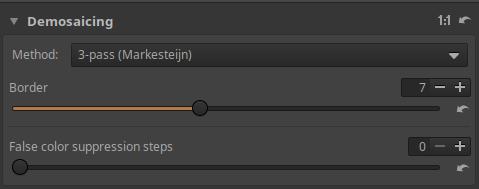

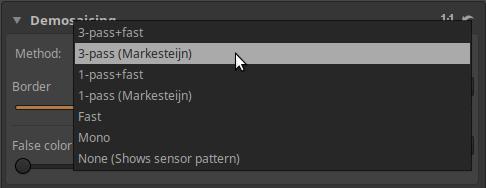

4.7.1.1 Demosaicing

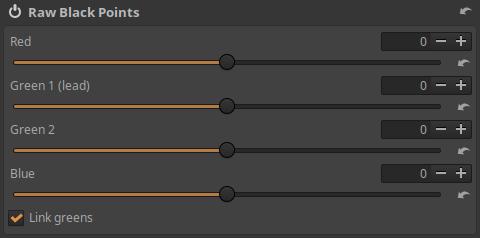

4.7.1.2 Raw Black Points

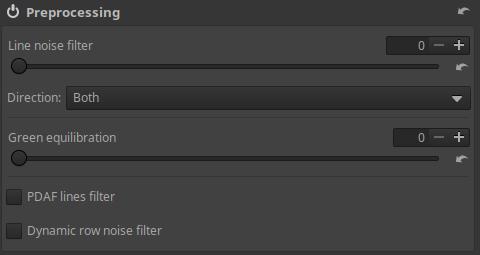

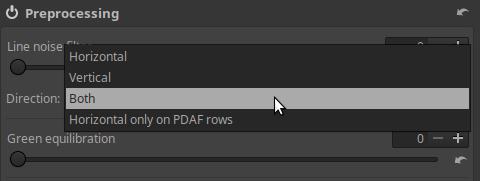

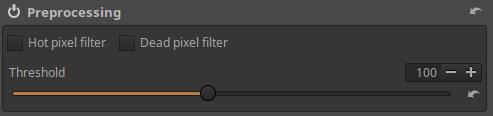

4.7.1.3 Preprocessing

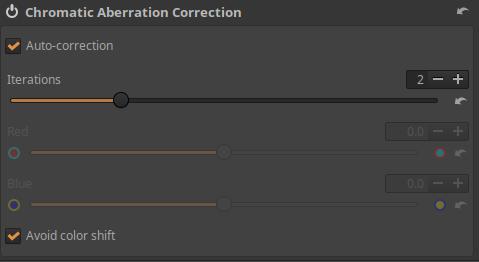

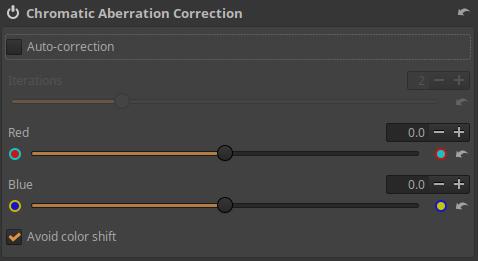

4.7.1.4 Chromatic Aberration Correction

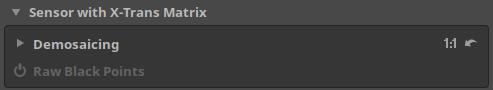

4.7.2 Sensor with X-Trans Matrix subgroup

4.7.2.1 Demosaicing

4.7.2.2 Raw Black Points

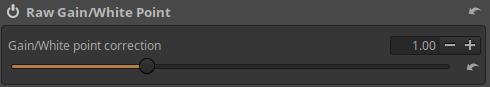

4.7.3 Raw Gain/White Point

4.7.4 Preprocessing

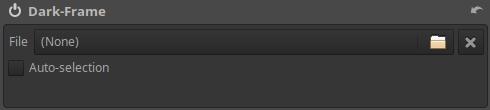

4.7.5 Dark-Frame

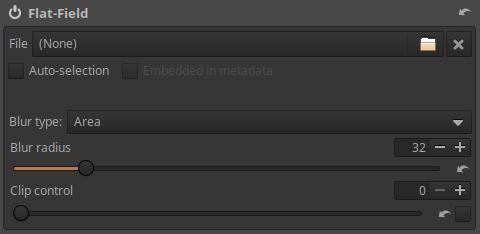

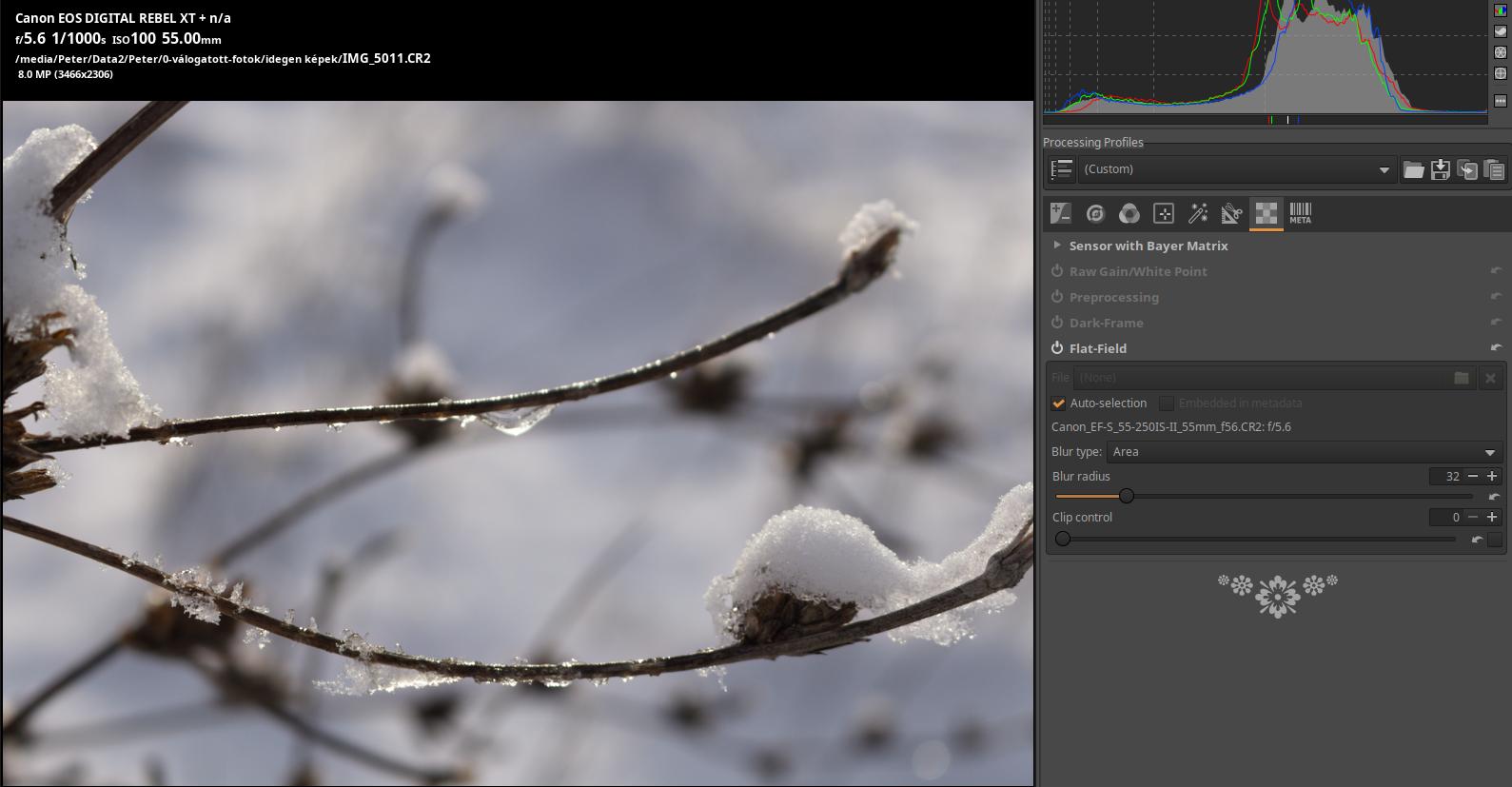

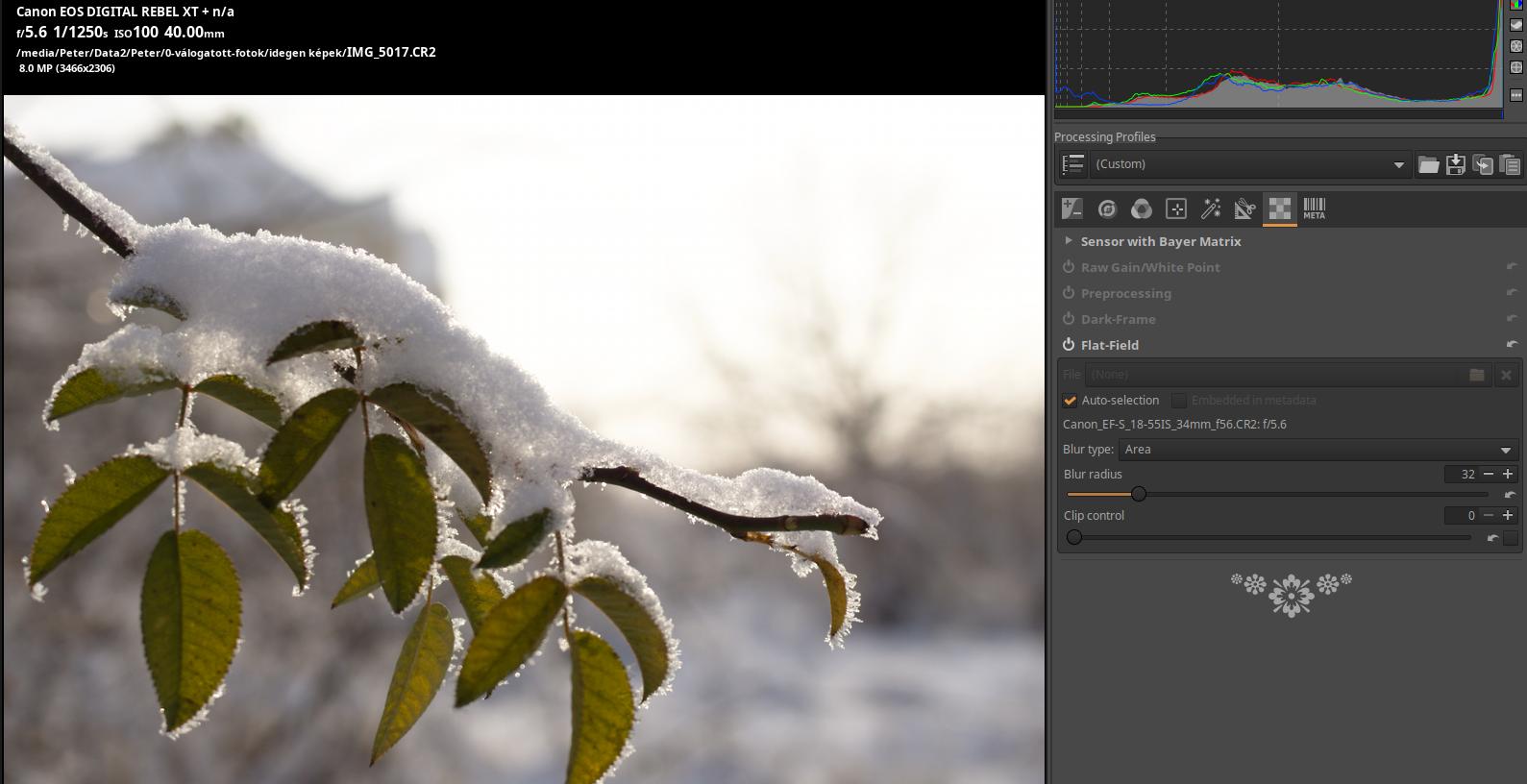

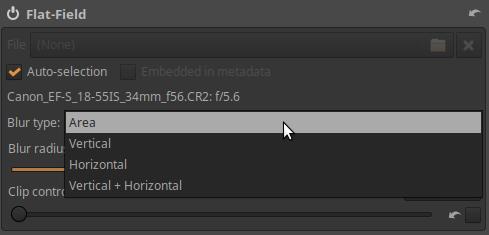

4.7.6 Flat-Field

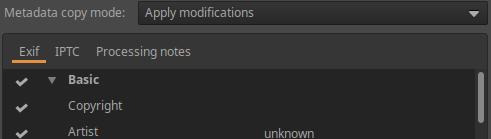

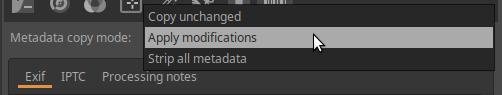

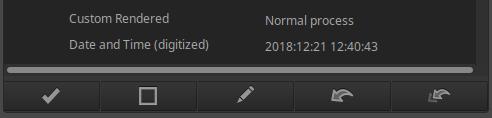

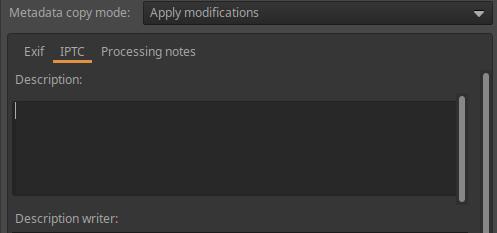

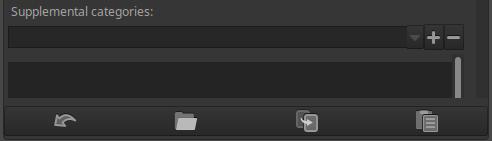

4.8 Metadata group

5. Final words

Legal information

This book is copyrighted. Its use is permitted only under the terms of the Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 (Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License).

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.hu

Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Book Title: The ART Raw File Processing Program

Copyright Peter Bereczky, 2025

Second revised and expanded edition, 2025

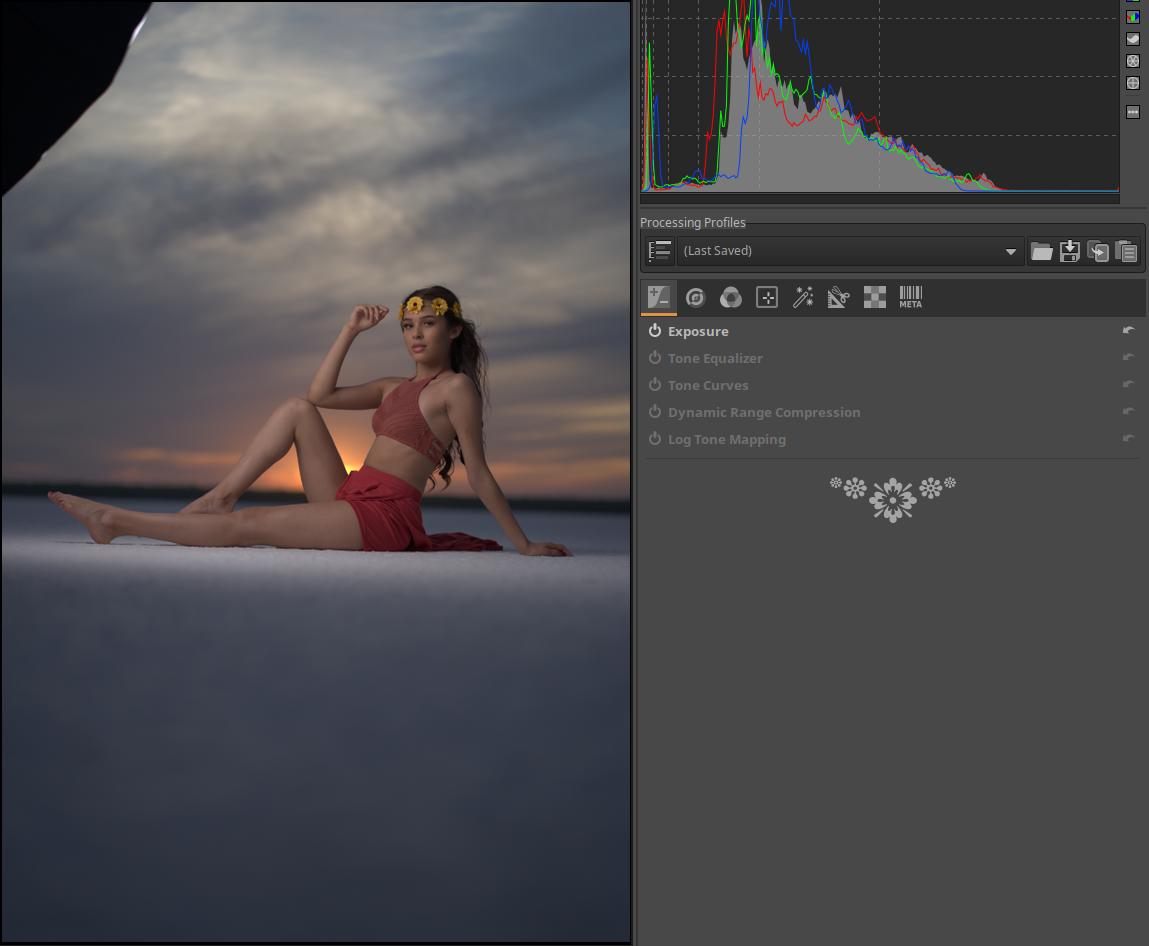

Cover photo: Photo by Jit Roy from Pexels

This book is based on ART 1.25.3 and CTL scripts version 1.2.

The source of the raw files (“images”) shown in the book (which can be downloaded from here): signatureedits.com. Where I deviate from this, I will indicate it separately.

Sources

Recommendation

I dedicate this book to my partner, Katalin Nánási,

and I recommend it to our children, Eszter and Gábor.

1. Introduction

Anyone who wants to take photos more seriously is faced with the need to post-process their images. Without this, there is no way the image will be one that the creator would be satisfied with. We want to create images that have an emotional impact, and we can achieve this through post-processing, among other things. The need for post-processing also entails shooting in raw format. This is the only way we will be able to make significant changes to our image, which is not possible in JPEG format.

This book is about the ART raw file processing program, which was created by programmer Alberto Griggio based on the code of RawTherapee. ART is a free, open-source program that runs on Windows, Linux, and macOS platforms and has a user interface in several languages. Its main purpose is to produce high-quality image files by processing raw files. Image files (e.g. JPEG, PNG, TIFF, etc.) can also be modified with it.

ART is the easiest program to learn among the other powerful, free programs for similar purposes (ART, darktable, RawTherapee). It contains very powerful editing tools with great possibilities. By using masks, we can modify certain areas of the image, not just the entire image. We can also use CTL scripts, which greatly increase the functionality of ART. With ART, we can create high-quality images. ART is able to fully satisfy the needs of most photographers.

ART and other similar programs are very complex, so learning them is not easy. Processing raw data is not easy. We can only be successful if we devote the right amount of work and time to it.

I hope my book will help beginners get started, and will also be a useful read for advanced users, who will experience success using ART.

I owe a great debt of gratitude to my partner, Katalin Nánási, who was my companion throughout my adult life and who provided significant support in the completion of this book.

The writings and images in this book are protected by copyright, please read the license terms above before using them.

I wrote this book because I wanted to leave something behind for the people from whom I received so many beautiful and good things.

I have tried to act with the greatest possible care, but errors may still occur. For this reason, I ask for the forgiveness of my readers.

The author

2. Basics

To process raw files, you need to understand the basic concepts. You can’t edit effectively if you don’t know what you’re doing. This chapter is about the basic concepts.

Post-processing is not always necessary. If you don’t have high expectations for the image, it may be unnecessary. For example, in the case of memorial picture or family photos, it is not necessarily necessary, and a JPEG image taken by the camera may be sufficient. To some extent, the camera also provides the ability to influence certain properties of the image by setting the appropriate picture style.

A computer program is not a panacea. Good results can only be achieved with precise work.

The raw data file is not an image, but a set of data, but for the sake of simplicity I (like others) will use the term “image” instead. But we should know that this is not an exact definition. I will not always emphasize that we open the image file or the raw file for editing, for example. Instead, I will write that we open the image for editing.

It is important to understand that ART is not a general image editing program like GIMP or Photoshop, but has a completely different function. It is designed to process files containing raw data (and not primarily image files such as JPEG, PNG, TIFF). However, it can also process image files.

2.1 The raw file

Raw is not an acronym, so it not need be written in all capital letters. The correct spelling would be raw. However, most often we see it written as RAW.

All cameras are capable of shooting in JPEG format, and it is the most common image format today. You can shoot in raw format with a wide variety of cameras, including virtually all interchangeable lens cameras and many others. Check your camera’s user manual for the options. You can select to shoot in raw format in the menu of cameras that support it, usually under the image quality menu. You can choose RAW, which means the camera will only create a raw file on the memory card and not create a JPEG image. The other option is to choose RAW + JPEG, which means the camera will also create a JPEG image, which is usually the highest quality, in addition to the raw file.

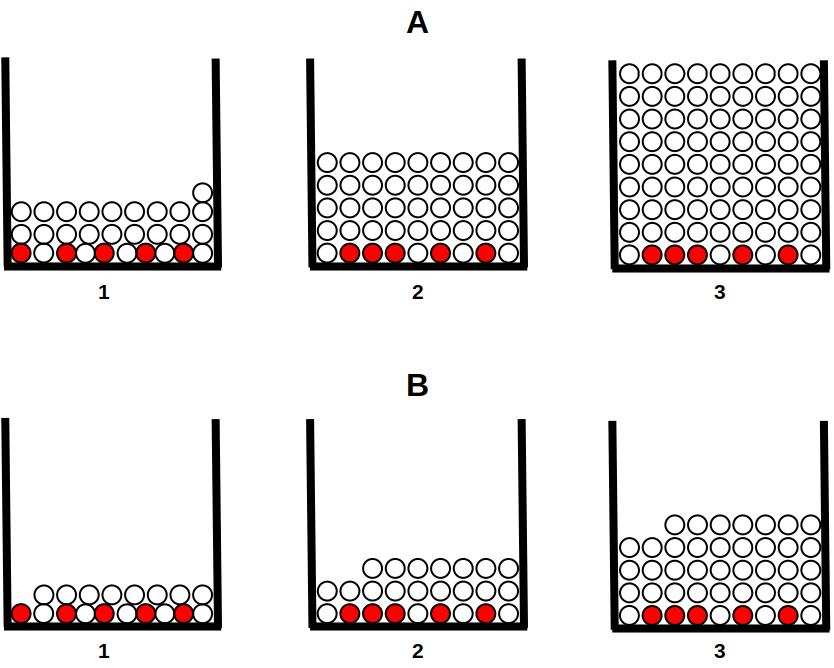

In a digital camera, the image sensor is a light-sensitive component, onto which the lens projects the image. The image sensor divides the projected image into tiny dots, called pixels. The set of pixels forms the digital image. In order to divide the image into pixels, small elementary sensors are arranged on the surface of the image sensor (in most cases) in a square grid. It is as if we were looking at a school “checkered” notebook, and each square would have an elementary sensor. The elementary sensors are arranged in rows and columns. In the figure above, the arrow points to an elementary sensor. In reality, elementary sensors are very small, they are not even visible to the naked eye, their number is in the millions. We can say that the number of millions of elementary sensors on the image sensor is the number of megapixels (MP) the maximum resolution of the image sensor (and therefore the camera).

The part of the image above in the yellow frame is shown enlarged in the figure below.

A digital image is made up of pixels. The individual pixels are clearly visible in the figure. A pixel is the smallest, distinguishable part of a digital image. The entire surface of each pixel is a certain color.

The elemental sensors detect light, not color. The part of the image sensor where the lens projects the darker part of the subject receives less light. The sensor receives more light in the lighter parts of the subject. After exposure, the data is read from each elemental sensor and converted into numbers. This conversion into numbers is called digitization.

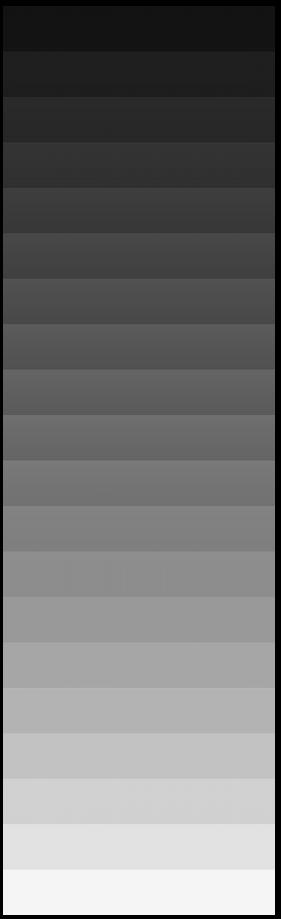

The figure above shows a tonal scale, from the darkest to the lightest tone, with a seemingly gradual transition. For the sake of the example, let’s imagine that our digital camera is able to process this tonal range. From each elemental sensor can read out a signal proportional to the amount of light it receives, and this signal must be converted into a number when digitizing. The resolution of the raw file is characterized by the bit depth. The camera’s specification shows how many bits the raw file produces. In practice, the resolution of the raw file is usually 12 or 14 bits. I will not go into detail about digitization, but I will only mention that the 12-bit raw file can store tones in extremely fine steps by dividing the entire tonal range into 4096 parts, and the 14-bit file can store tones in extremely fine steps by dividing the tonal range into 16384 parts, and extremely fine differences in tones will be distinguishable. This is one of the great advantages of raw files. The term “resolution” here should be distinguished from the resolution of the image sensor mentioned above. This refers to the finer increments in which the raw file can store tones, while the resolution of the image sensor refers to the number of elementary sensors on it.

The overflow of elementary sensors is often illustrated with the example of a bucket and rain. The bucket represents the elementary sensor, the rain represents the photons, and the time the bucket is exposed to the rain represents the shutter speed. There is a similarity between a bucket exposed to rain and an elementary sensor that collects an electric charge proportional to the amount of light falling on it. If we expose the empty bucket to the rain and leave it there for a certain time, we can measure how many liters of water have fallen into the bucket during that time. If we leave the bucket in the rain for a long time, after a while the bucket will be full, that is, it will become saturated, and the water that falls into it will flow out. After this, we can no longer measure how much water actually fell into the bucket, because we only find water corresponding to its entire volume in it, we have no information about how much water fell into it after saturation, which immediately flowed out. The elementary sensor behaves in the same way. If it is hit by too much light, it saturates, and even if there were more charges, only the signal corresponding to the maximum amount of charge it can absorb is read from it, the effect of the other charges is lost, not utilized, and thus clipping occurs. An elementary sensor with a larger surface area can usually store more photons, a sensor with a smaller surface area can store fewer.

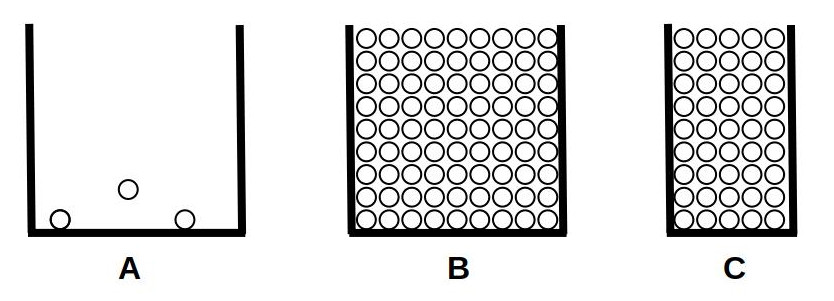

In the figure above we can see three elementary sensors, which are illuminated by photons from above. The elementary sensor shown in figure “A” is not illuminated, so only some image noise can be read from it. In figure “B” we can see a larger elementary sensor saturated, and in figure “C” we can see a smaller one, also saturated. We can see that the elementary sensor with a larger surface area can store much more charge.

Clipping is caused by the overflow of the elementary sensors. The main source of image noise is thermal noise produced by the image sensor and its associated components (signal amplification circuitry, etc.), which is caused by the thermal motion of molecules in the components.

It is useful to know that the sensitivity of the image sensor is constant and cannot be changed. If we shoot with twice the sensitivity (e.g. ISO 200 instead of 100), then half the amount of light reaches the image sensor, because we have to take the picture with either half the shutter speed or one value narrower aperture in order to get the correct exposure.

A: low sensitivity (ISO 100)

- Dark areas

- Midtones

- Highlights

B: twice the sensitivity (ISO 200)

- Dark areas

- Midtones

- Highlights

The red circles represent image noise, the white ones represent the amount of charge caused by useful image information. In the top row of the figure, we photographed with low sensitivity (ISO 100). We can see three elementary sensors, the one on the left received little light from the dark subject, the one in the middle received more from the midtones, and the one on the right received the most from the brightest tones. Below we can see the case of double sensitivity (ISO 200). Due to the twice as high sensitivity, half the amount of light reached the sensor, therefore half the amount of useful charge was generated. However, the image noise did not decrease.

Due to the halving of the amount of light, the signal that can be read from the image sensor will also be half the size, which is compensated by doubling the gain of the circuit that amplifies the signal by setting ISO 200. Then, our signal in front of the signal digitizing circuit will be the same as when setting ISO 100, the huge difference will be that by increasing the gain, we also double the image noise. If we double the ISO sensitivity, we actually always double the gain of the amplifier. If we reduce the ISO sensitivity by half, we actually always reduce the gain of the amplifier by half. Despite this, we usually say that we are adjusting the sensitivity of the sensor.

Noise can still be seen when using a slow shutter speed, even at a low ISO setting. In this regard, a shutter speed of at least 1 second is considered slow.

The raw file is created as a result of processing in the camera. The main steps of processing are as follows:

- After exposure, a signal proportional to the amount of light is read from each elementary sensor, and the read values are digitized.

- The JPEG image is produced using the digitized data according to the camera’s set parameters (such as picture styles).

- If raw shooting is enabled, it creates the raw file by embedding the created JPEG image, using the unprocessed raw data, as well as metadata.

- Finally, the raw file is saved to the memory card and, if enabled, the JPEG image is saved.

The JPEG image embedded in the raw file is used by various software programs to display the image whose raw data is contained in the given raw file. The metadata embedded in the raw file and the JPEG image is information related to the creation of the image (e.g. camera type, lens type, ISO value, shutter speed, aperture value, etc.), which can be read and viewed at any time with a suitable program.

So, the raw file contains the unprocessed data read from the image sensor, digitized with high bit depth, the metadata, and the embedded JPEG image.

2.2 Demosaicing

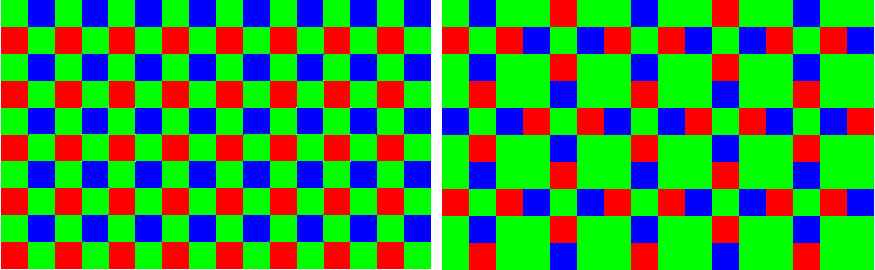

The image sensor does not see colors, it only detects the amount of light. In order for us to see colors in the image, each element of the sensor (“pixel”) has a red, green, or blue filter in front of it, which only allows light rays of the color corresponding to its color to pass through.

Bayer color filter on the left, X-Trans color filter on the right. Image source: Wikipedia

In the figure, a small square corresponds to a pixel (an elementary sensor) of the image sensor. We can see the color filters arranged in a strict order in front of the elementary sensors. A pixel detects only the intensity of one color. The color of a pixel in a photograph is determined by calculation by taking into account the data of the elementary sensors located around it, under different colored filters, and the characteristics of our vision. This process is called demosaicing. So the color data of each pixel is created during the demosaicing.

On the right side of the figure you can see a small detail of the X-Trans matrix color filter developed by Fujifilm, which is significantly different from the Bayer color filter shown on the left. Fujifilm cameras use the X-Trans matrix color filter, while other manufacturers use Bayer color filters. The same demosaicing algorithm cannot be used for the Bayer and X-Trans filters. Several demosaicing methods have been developed for both types of sensors, from which we can choose during processing.

2.3 Raw black level, Raw white level

Raw files contain data captured by the sensor and quantified during digitization. The lowest brightness values are assigned to the lowest numbers, and the highest brightness values are assigned to the highest numbers. One of the key pieces of information needed to properly process the data from a raw file and display it as an image is the raw black level and raw white level.

The raw black level determines the lowest brightness value from which the data in the raw file can be used. Values below this are not used during processing, they are considered the same as the raw black level value. For example, in the case of a 14-bit raw file, the raw black level is not necessarily 0, but the usable range can start with a value of 512, for example. The reason for this is that the image sensor and the camera electronics also produce noise. It is only worth using the signal when the useful image information dominates over the noise. If the detail of the subject in question is very dark, so little light may reach the elementary sensor that the noise, not the useful signal, may dominate.

The raw white level determines the lightest shade value that can still be used. The white level of a raw file containing 14-bit data is not necessarily 16383, its value depends on several factors (e.g. overflow of the elementary sensors), and can be, for example, 16300 in reality.

2.4 Color management, color systems

We need some basic knowledge of color management when processing raw files. This is a complex, multifaceted topic that could fill books. However, we don’t need such detailed knowledge, just enough to understand what we are doing when processing a raw file. In this section, I will briefly cover the most basic knowledge that can help you get started.

Human vision is a very complex thing, very difficult to describe mathematically. Several color models with different approaches have been created. In the case of different color systems (color spaces) used in certain imaging (scanner, camera, etc.) and display (monitor, printing press, printer, etc.) units, it would be necessary to ensure that an image appears the same on all of them and that they can be converted into each other. This is a difficult problem to achieve. The individual display units and color system models are not able to transfer, map, return, or depict the entire range of colors visible to humans, but only a larger or smaller part of it. Here, without claiming to be complete, I will describe the most important basic concepts related to color systems and color representation that also occur in programs used to process raw data.

I will not go into detail about our vision, because it is not needed to process images. However, I will mention that our vision has two stages. On the one hand, there are the light-sensitive cells and their properties, and on the other hand, the colors that are created by the complex processing of the information obtained from them, and the resulting image. The colors that we perceive are actually not created on the retina, but in our brain, during the processing of information. The processing of information obtained from our eyes is very complex, and at least 30 different areas of our brain are involved.

The colors of objects are not physical properties of objects, they are created in our brains and exist only for us. For example, animals perceive colors completely differently. It is difficult to believe that the color of an animal that stands out from its environment is a camouflage color. However, if we learn about the vision of the animal’s enemies, we can see that for them an animal with camouflage color blends well into its environment. So colors are created in our brain, but other conditions also affect it. Our color perception also depends on the circumstances. Optical illusions exploit this. In the simplest case, for example, we can see a surface of the same color as having different tones depending on the color of the background. Or consider that we perceive a white sheet of paper as white even under the light of a traditional incandescent lamp, although in reality it looks yellow. We can verify this by photographing it with a daylight white balance. Our brain “knows” that in reality the sheet of paper is white, so we see it as white.

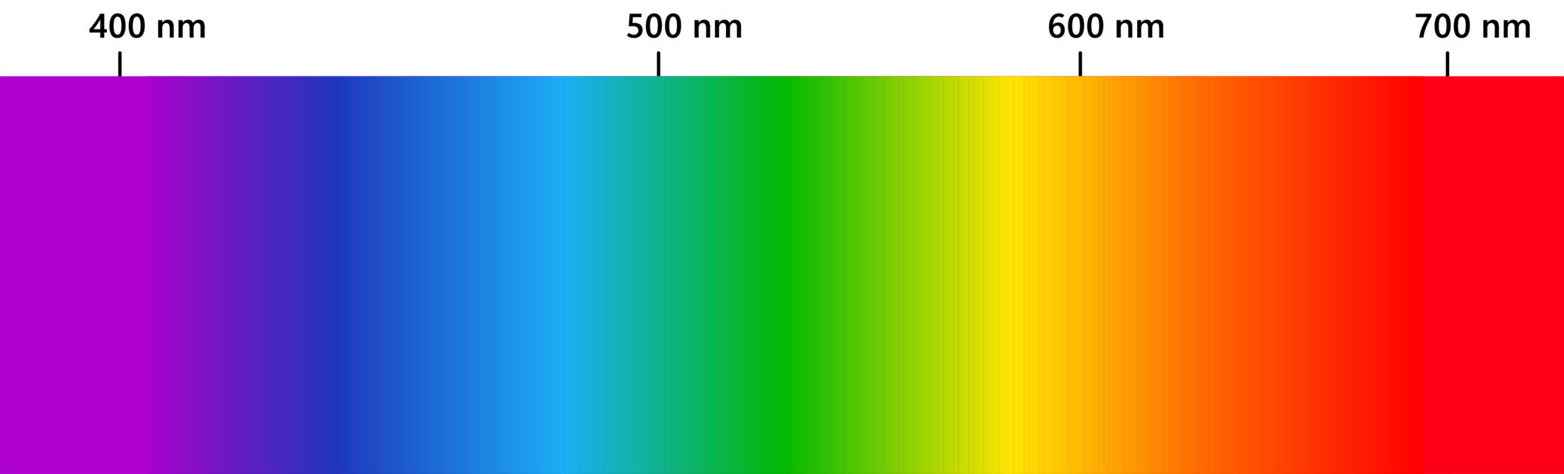

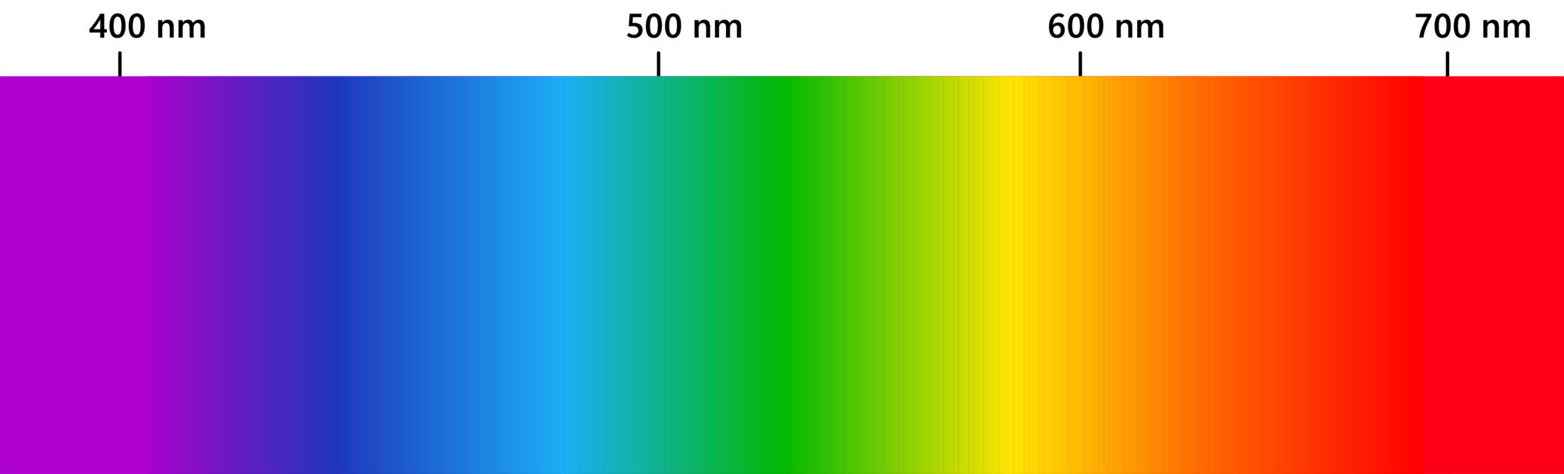

The wavelength range (spectrum) of sunlight that a person with average vision can see is 380-750 nm (nanometers). The color that is perceived depends on the wavelength of the light. The diagram below shows the part of the sunlight spectrum that we can see.

The wavelength values are shown above, and the corresponding color below. In fact, we see the colors of the rainbow, from violet to red. In a rainbow, the components of visible light with different wavelengths appear shifted relative to each other, which is why we can see the color shades that make up the rainbow next to each other. We saw the same thing in the school experiment when we used a glass prism to break sunlight into components, and we got a result similar to the rainbow. This is possible because the refractive index of glass depends on the wavelength of light, it deflects electromagnetic radiation with different wavelengths to different degrees, which is why colors with different wavelengths will be visible next to each other.

When sunlight is broken down into components using a prism, we get a series of monochrome (single-color, single-wavelength) components. So the spectrum shown in the figure above consists of a succession of monochrome components. The spectrum of sunlight is continuous, meaning that it contains components of all wavelengths within the entire wavelength range. The result of these monochrome components of different wavelengths and intensities is perceived as “white” light.

Color spaces are about the mathematical modeling of colors that humans can perceive, or a subset of them. By colors here I mean “everything” that we can perceive. This includes gray, black, white, pastel colors, strong colors, in short, everything. The description in the language of mathematics is necessary for the applicability on the computer. For each color space, there are parameters whose values determine the given color. Changing a given parameter changes some characteristic of the given color. In image editing programs (among others), we can directly or indirectly change these parameters, which result in changes in the image. Therefore, it is important to have at least a basic understanding of color systems. We need to understand what we actually change when we change something in the program.

A concept also related to color spaces is side effects. It would be good if, during editing, only the desired characteristic (for example, contrast) changed, and everything else (for example, hue, saturation) remained unchanged, but this is not always possible. It may happen that if we change something, other characteristics also change as a side effect. For example, if we adjust the brightness of the image, the colors would also change slightly as a side effect. This is not good, because if everything changed at the same time, the whole thing would be unmanageable. That is why we need multiple color spaces, multiple methods (procedures) during image editing and raw file processing. One is more suitable for this purpose, the other for another purpose. By using multiple color spaces and multiple methods, it is possible to create a work environment that is easy to use, has as few side effects as possible, and gives good results.

Making too drastic a change can have side effects. This can be avoided by using editing tools in a way that doesn’t overdo it.

2.4.1 Two types of frameworks

There are two frameworks within which color properties can be analyzed and described:

- A physiological framework that is proportional to the brightness of the subject (linear), focusing mostly on the response of the cones on the retina, using color spaces such as CIE XYZ 1931 or CIE LMS 2006.

- A perceptual, psychological framework that also takes into account brain corrections, for example using the CIE Lab 1976, CIE Luv 1976, CIE CAM 2016 and JzAzBz (2017) color spaces.

These two frameworks provide us with the ability to describe colors and allow us to change certain properties of colors without changing other properties (much).

Colors can be described in many different color spaces, but regardless of the color space, at least three characteristics are required to describe every color: a measure of brightness (lightness), and two measures that describe the color in some way (in the form of hue and saturation, or using color coordinates).

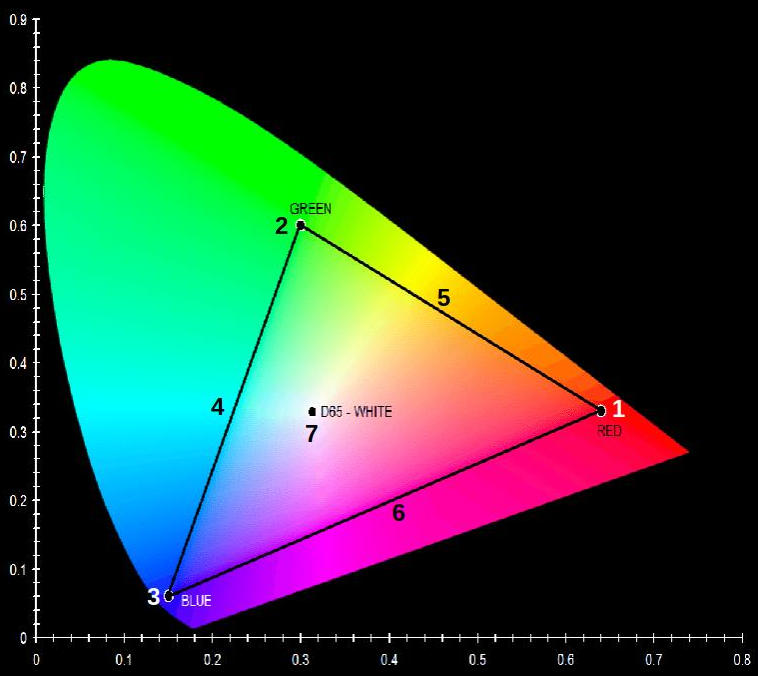

2.4.2 The CIE XYZ 1931 color system

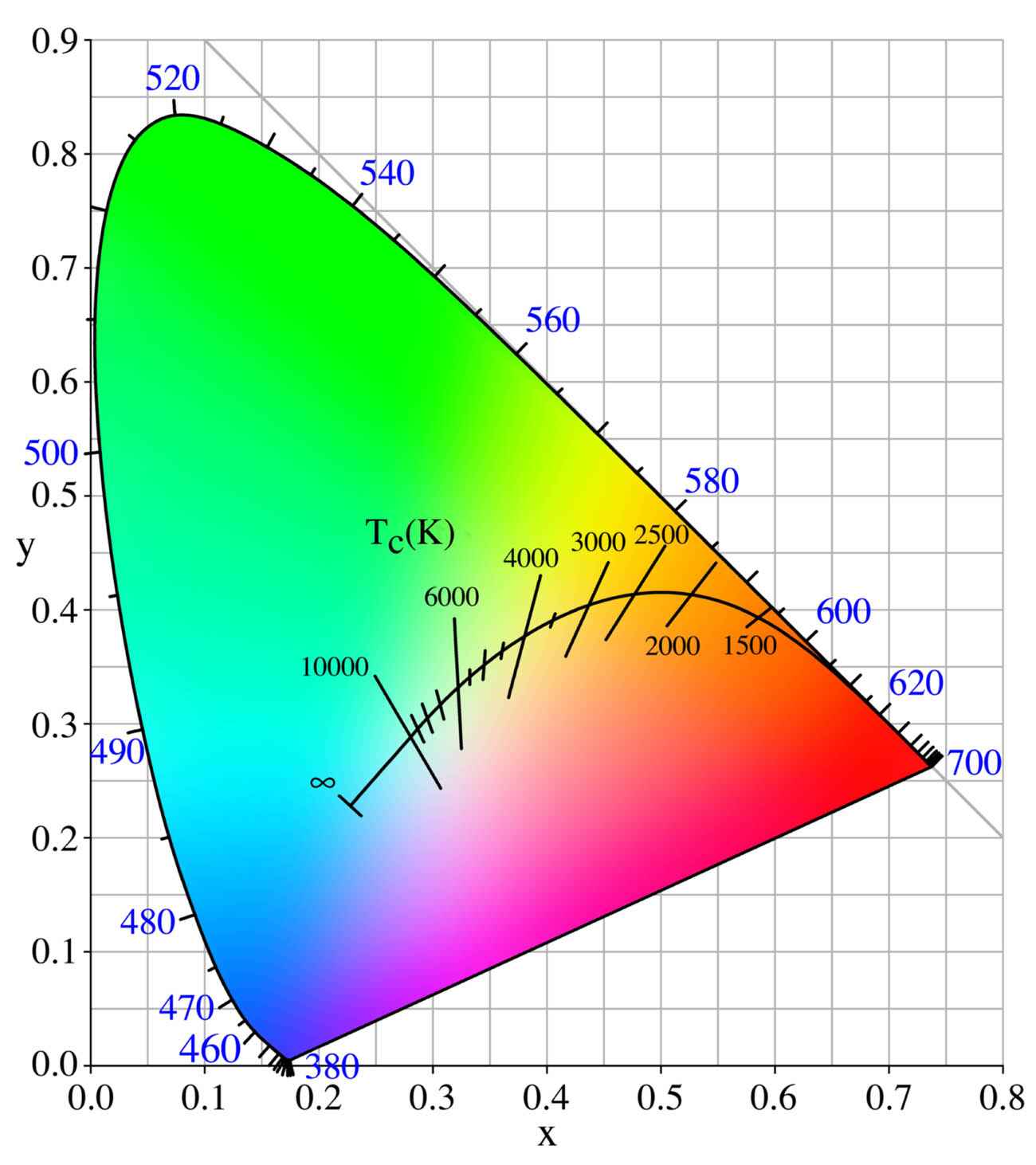

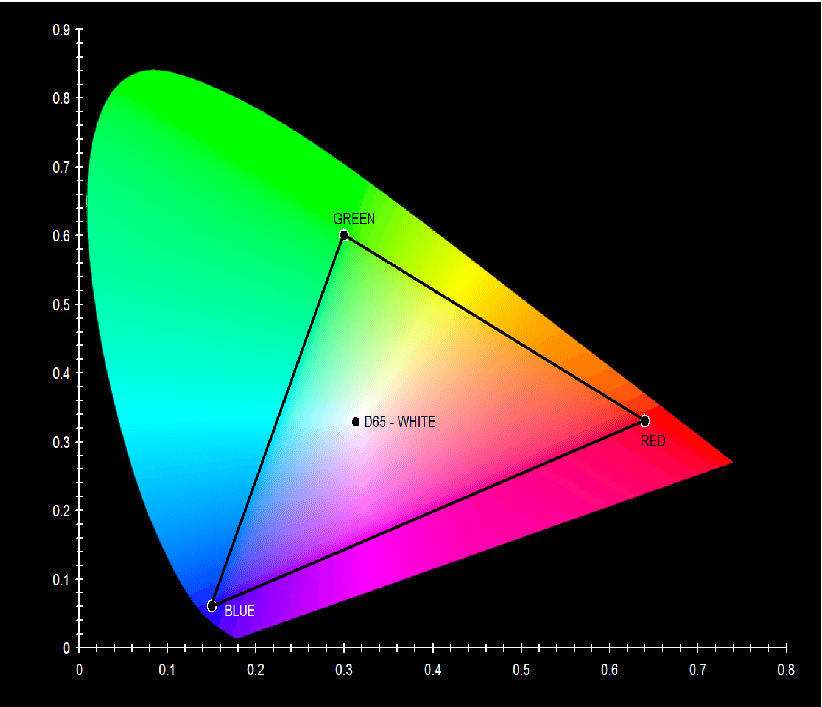

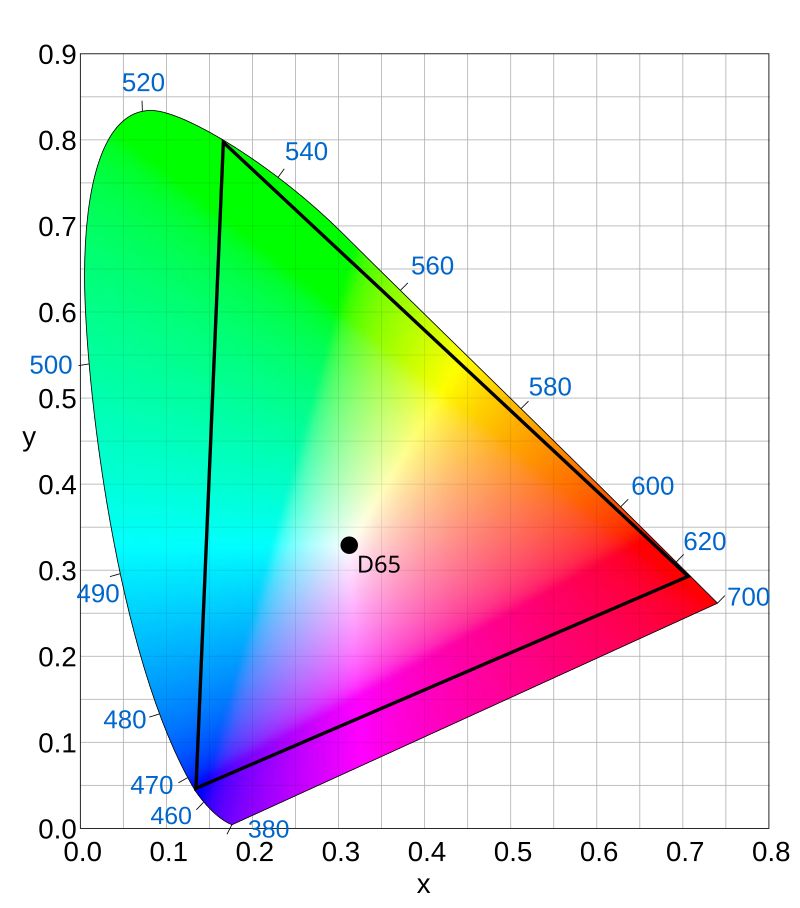

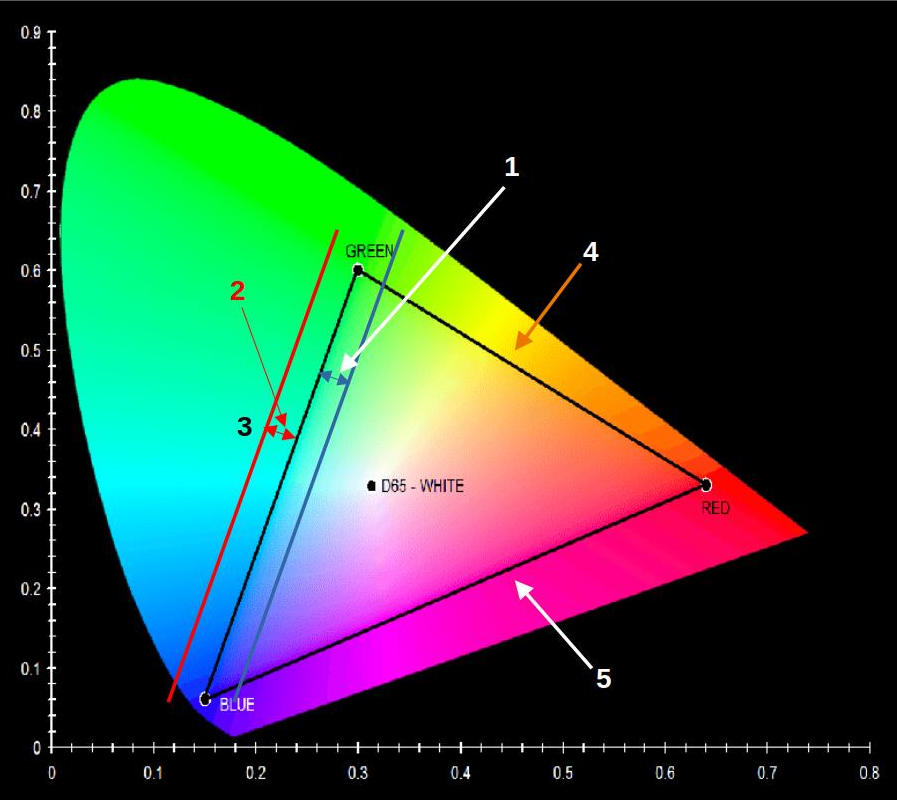

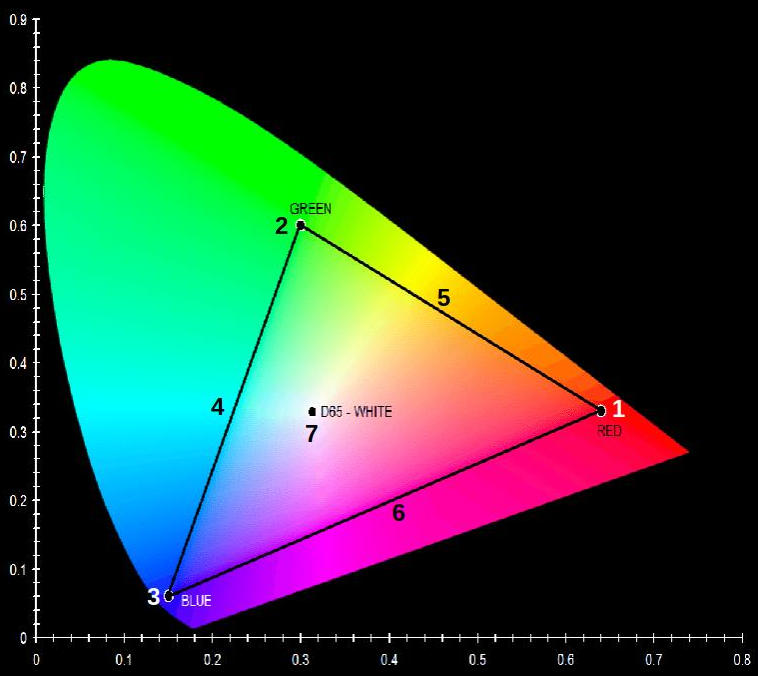

Because of these three characteristics, the range of perceptible colors can be described by a three-dimensional shape. The figure above shows a projection of the CIE 1931 XYZ color system (the three-dimensional shape). This projection shows most of the color shades that humans can perceive. This is the largest range of colors that humans can perceive. Colors that are no longer perceptible lie outside the color space shown in the figure.

In the diagram above, we can theoretically see all the colors that humans can perceive at a certain brightness (“lightness”). However, this is only theoretically the case. In reality, the image shown here is a JPEG image that is only suitable for displaying a smaller range of colors that humans can perceive, and therefore cannot realistically contain all the colors that can be perceived. The other problem is the color range that a monitor can display. A monitor whose color range can approach the full color range that humans can perceive is very, very expensive. Cheaper monitors fall far short of this, so we can’t realistically see the colors of the projection of the CIE 1931 XYZ color system shown in the diagram above.

In the figure, the wavelength values of the monochromatic light obtained by breaking down sunlight into its components are indicated at the edge of the colored area. These are the monochromatic components also shown in the figure above (sunlight spectrum). The exception to this is the straight part shown at the bottom edge of the diagram.

We can produce mixed colors by mixing two or more monochrome components (with a certain intensity ratio). If we connect any two monochrome colors located at the edge of the colored area of the above figure with a segment (a straight line), then along the segment we can see what mixed colors we can produce by mixing those two monochrome colors in different proportions. If the intensity of the two monochrome colors is the same, then the mixed color is located at the midpoint of the segment. We can conclude that the mixture color obtained by mixing two or more visible monochrome colors in different proportions is perceived as a different color.

Similarly, any two points inside the colored area can be connected with a segment. At both endpoints of the segment there is a mixed color. Along the segment we can see what colors can be produced by mixing those two colors in different proportions. In the case of the same intensity, we get the color visible at the midpoint of the segment.

The colors located along the line visible at the lower edge of the color space are mixed colors, and are created by mixing the colors with wavelengths of 380 and 700 nm visible at the two ends in different intensity ratios.

So, the colors located at the edge of the horseshoe-shaped part of the diagram represent spectral (found in the daylight spectrum) monochrome colors, which can be characterized by a single wavelength. The colors located inside the horseshoe-shaped part and along the bottom straight line can only be produced as mixtures of spectral monochrome components, or two mixed colors in different proportions, which means that there is no single wavelength of light that we would see as the same color.

The figure also shows that a certain mixed color can be produced in more than one way. Let us mentally connect a left and a right extreme point of the horseshoe-shaped part with a segment. Let us mentally select an intermediate point around the middle of the segment. At this point we see a certain mixed color. Now we can see that there are countless ways to connect the extreme points of the horseshoe-shaped part with a segment so that the segment passes through the point selected in the mind, i.e. results in the same mixed color. Similarly, there are countless ways to select two points inside the horseshoe-shaped part that, if connected with a line, pass through the selected point. So, a mixed color can be produced in countless ways from monochrome colors or mixed colors.

In the figure, we can read the x and y color coordinates of the hues, but we must also imagine a third (z) axis perpendicular to the plane of the monitor (on which we are looking at the figure), on which the lightness values are depicted. If we were to look at a section of this color space with higher brightness, the gamut (range of perceptible colors) would be smaller than shown in the figure above. This means that we no longer perceive lighter versions of certain hues. So a color can be described with the x, y, z coordinates. In this color system, lightness is theoretically independent of hue. This means that when the lightness is changed, the color does not change in principle.

So, looking at the above diagram of hues for a given lightness, a hue can be described by the x and y color coordinates. We do not perceive “colors” outside the color space.

On the color chart, the point with coordinates x=1/3 and y=1/3 is the white point, and the small area surrounding it represents the color white. If we draw straight lines from the white point to different points on the edge of the colored area, the color is determined by which extreme point of the colored area the given line reaches. From the white point to the extreme point of the colored area (along the line), the saturation increases. At the white point, the saturation is zero.

In the figure, the curved line actually represents the color temperature of daylight illumination. Along this curve, the color temperature (color) of the light illuminating the subject changes under daylight conditions depending on geographical location, time of day, and other factors (e.g. weather, shade, etc.). Some color temperature values are also marked in the figure. We may also encounter other notations of the more important color temperature points, in which the 6000 K color temperature point is marked as D60, 5000 Kt as D50, 6500 Kt as D65, etc. in a figure similar to this one.

Our central visual field, which we use for the most detailed, sharpest vision, has a visual angle of about two degrees. Like when we focus on a circle visible under a visual angle of two degrees. The CIE 1931 XYZ color system deals with perception at a visual angle of two degrees and does not take into account our peripheral vision. There is also a color system that examines a visual angle of 10 degrees, i.e. it partially takes into account our peripheral vision.

2.4.3 RGB color system

The RGB color system is a collective term, as there are several different RGB color systems. The common feature of the various RGB color systems is that colors are produced from three primary colors, namely by additively mixing the primary colors of the appropriate intensity (as if we were projecting the three primary colors of different intensities on top of each other).

In all RGB color systems, colors are created by mixing three primary colors (color components) in a certain ratio. The three primary colors are red (Red - R), green (Green - G), and blue (Blue - B). We also say that there are three color channels in the RGB color system, red (R), green (G), and blue (B). A given color can be characterized by a triplet of numbers that gives the intensity values of the three primary colors in the order R, G, and B that result in the given color.

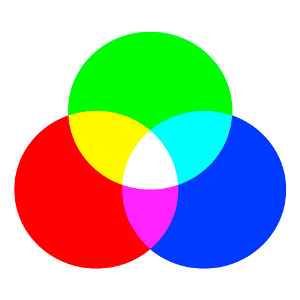

In the figure we can see that if we projecting the three primary colors on each other with maximum intensity, we get white. Therefore, due to this property, this method of color mixing is called additive color mixing.

There are RGB color systems that cover a significant part of the full range that humans can perceive, and there are those that cover only a small part of it. There are those in which the lightness values are linear, and there are those in which they are not. The former are mostly used for image processing purposes, while the latter are used for display (for example on a monitor), because this requires nonlinear characteristics.

Let’s take a brief look at the sRGB color space. JPEG images most often contain information in the sRGB color space. The figure below also shows the CIE 1931 YXZ color space. It shows the colors and color range of the sRGB color space, which is the most common color space today.

The color tones that can be displayed in the sRGB color system can be seen inside the triangle. At the vertices of the triangle we find the three primary colors of the sRGB color system (red, green, and blue). The colors seen inside the triangle are created by mixing the three primary colors at different intensities. The colors created by mixing the primary colors cannot be outside the area bounded by the lines connecting the three primary colors (outside the triangle in the figure). We can also see the point D65 (6500 K) in the figure.

In the case of sRGB, each of the three color channels has an 8-bit resolution, meaning that 256 different lightness values (intensity values) are possible. The ratio of the intensity values of each color channel determines the ratio of the individual components. A given color is therefore defined by a combination of three values: the intensity values of the red, green, and blue channels. In this color system, a total of 256x256x256=16777216 color shades are theoretically possible.

The primary colors are chosen so that if all three color channels are at maximum intensity, their mixture gives the maximum brightness white. If all three color channels are the same, but not at maximum value, then we get a neutral gray. If all three color channels have a value of zero, then we get the darkest shade, black. Colors can be specified with a triplet of numbers, namely by specifying the intensity values of the primary colors that result in a given color in the order red (R), green (G), and blue (B). For example, [0,0,0] denotes black, [255,255,255] denotes white, [240,240,240] denotes light gray, and [230,200,50] denotes ochre yellow. For example, if only the R channel has a value other than 0, then we get a red color, the smaller the numerical value, the darker it is. Due to the 8-bit resolution per color channel (“color depth”), we can only get 255 different shades of red ([1,0,0,] - [255,0,0]).

The concept of a color channel can mean, on the one hand, the intensity value of a color component of a given pixel, for example, in the case of [100,200,150], the value of the R color channel is 100, and on the other hand, it can also mean the ordered set of intensity values of a given color component belonging to all pixels of a given image. In the latter sense, for example, the green color channel of an image means the ordered set of intensity values of all pixels of the image belonging to the green base color. It is ordered because we know which value applies to which pixel, the values are not in a jumble.

The situation is complicated by the fact that the sRGB color system is also called 24-bit. They say that to describe a color, three eight-bit numbers are required, corresponding to the three color channels, i.e. a given color can be described in this color system with a total of (3x8=) 24 bits. So when we talk about the bit depth of a color system, we need to say how many color channels there are, how many bits they are, and whether we are talking about the bit depth per color channel or the combined (added) bit depth of all color channels.

We can see how small a range of all visible colors can be displayed in the most commonly used sRGB color system. Our monitors, phones, tablets, and televisions use this color system, and we also use this color system to create JPEG images with our cameras. This is useful because we can display this well on our monitors, televisions, and such images are also displayed on the Internet with correct colors and tones.

We might think that the sRGB color system is great because it can distinguish over 16 million shades of color, and our vision is nowhere near that. The problem is that all 16 million shades of color are within the triangle, and colors outside of it cannot be represented or displayed.

An average, not very expensive monitor is not nearly capable of displaying all the shades perceived by humans, but it may be capable of displaying (almost) the entire sRGB color space.

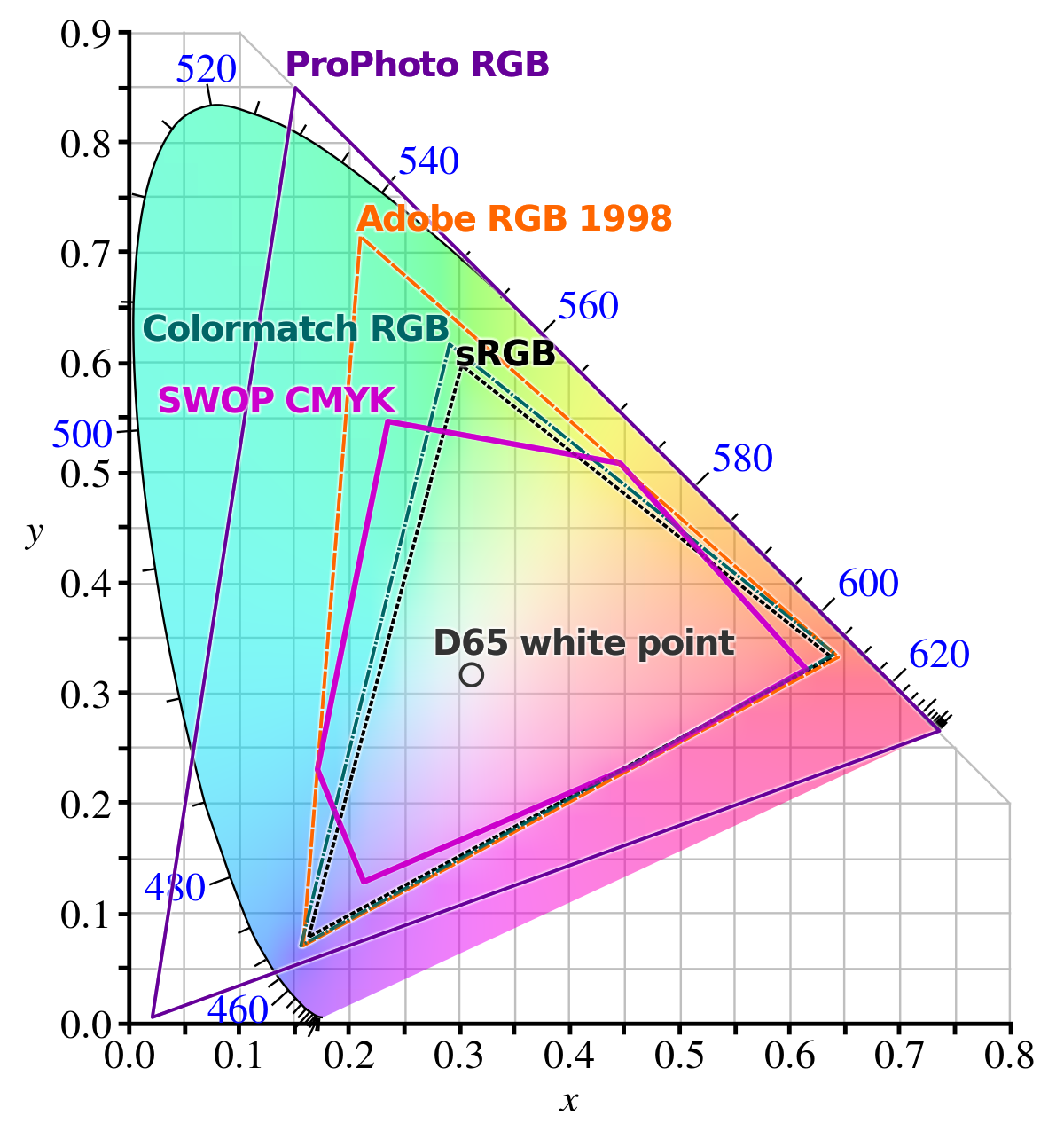

Let’s look at the figure below, which also shows the CIE XYZ 1931 color space, with the color ranges of some other color spaces also marked:

The Adobe RGB 1998 color space is much larger than the sRGB color space. To achieve a larger color space, at least one of the primary colors must differ from the sRGB primary colors. This is exactly what happens, as you can see that the green primary color (the green vertex of the Adobe RGB triangle) is much higher in the figure than the green vertex of the sRGB, resulting in a larger color space. Finally, let’s look at the ProPhoto RGB color space, which covers almost the entire spectrum and is even suitable for representing “colors” that are not perceptible to humans, for example at the lower left vertex. This is a linear color space that can represent colors at high resolution (with a high bit depth). It is also used, for example, as a so-called working color profile in raw file processing programs (in many cases, changes are made in this color space during processing).

2.4.4 CYMK color system

The CYMK color system is used in printing, and its color rendering ability is quite limited compared to human color vision. In the CYMK system, colors are produced using cyan (C), magenta (M), yellow (Y), and black (K - Key, key color), i.e., these colors are used for printing. Today, this is not entirely true, because more colors can be used for better results. This model is based on the color absorption of dyes. If we illuminate the dye with white light, certain wavelengths of light are absorbed, others are reflected, reach our eyes, and we see the dye as the color corresponding to the reflected light. A mixture of C, M, and Y dyes in the appropriate ratio is theoretically capable of absorbing the entire visible spectrum, i.e., we get black as a result. Because of this property, this color mixing method is called subtractive color mixing. In practice, however, mixing the three colors does not produce black (the result will be a brownish color), so black ink is also used for printing. If we want to print an image in the sRGB color system in a printing house, for example for publication in a magazine, then in theory only the color points that fall exactly within the common area of the two color systems can appear on the printout, and the color of the sRGB pixels that fall outside of that area will be converted in some way to a similar color that can be displayed in the CYMK system.

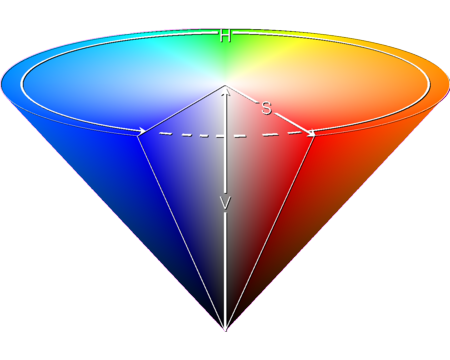

2.4.5 HSV color system

This is actually a different modeling of the RGB color system, closer to the concepts used in everyday life. Using the three color channels of the RGB color system, it is not easy to mix a given color, because this model is far from human thinking and concepts about colors. The HSV color system describes colors with hue (H) (in other words, hue: color character, color type), saturation (S), and value (V, lightness). Its usual name is even HSB, in which case the name Brightness (B) is used instead of Value. This model is usually represented by a cone turned upside down.

In the figure above, we can see the HSV color cone, with an article cut out of it on the side facing us. We can also observe the meaning of the H, S, and V parameters. In the middle, along the section from the tip of the cone to the middle of its base (the “V” in the figure), the shades of gray are located. The darkest (black) is at the tip, and the lightest (white) is in the middle of the base circle. The “V” value shows the lightness value in percentage, 0% is black, 100% is the lightest. The “H” value is given in degrees, and we can select the color using it. Its value can be between 0-360 degrees, with 0 degrees being red, 60 degrees being yellow, 120 degrees being green, 180 degrees being greenish-blue (cyan), 240 degrees being blue, and 300 degrees being magenta (the color between red and violet). The saturation “S” increases from the cone’s altitude line towards its surface along the radius of the circle, including any section circle of the cone parallel to its base circle. There is no saturation in the center (0%), so we get gray, and at the surface the saturation is 100%, where the most saturated colors are located.

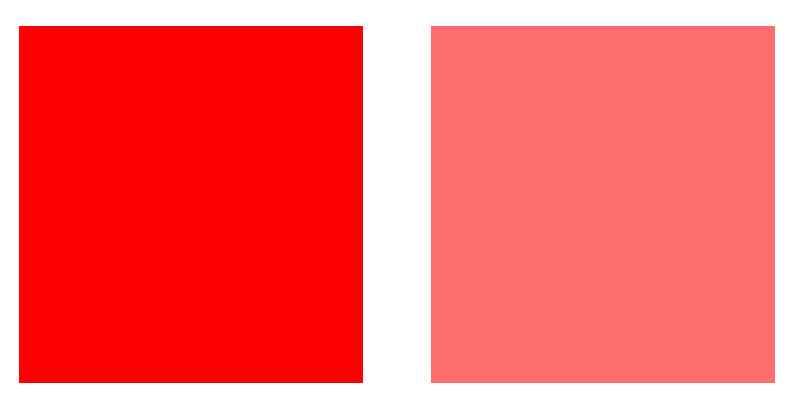

On the left is the more saturated version of the same color, on the right is the less saturated version

We see slightly saturated (1-10%) colors as gray, but we can already distinguish whether we see “warm” (reddish, yellowish) or “cold” (“bluish”) gray. Pastel colors have a saturation of 10-30%, in practice, the saturation of stronger colors experienced in our environment is usually 30-65%. 65-90% saturation characterizes saturated colors. 90-100% saturation belongs to oversaturated colors, which must be treated with caution, because color corrections change these colors little, so it is not possible to work well with them. In the figure below, we can see the basic circle of the cone in a top view, which is also called the color circle. The color changes along the outline. In the center of the circle, the saturation is 0%, it increases along the radius of the circle, reaching 100% at the outline.

We can also say that we select the “pure” color with the H value, increase or decrease the white content with the S value, and increase or decrease the black content with the V value. When the V value is 0, we get black regardless of the other two values. If the V value is 100%, then the color has the lowest black content. If we then select a color with the H value, the white content of the image is the highest at the S value of 0%, and therefore we get a white color. If we increase the S value, the selected color appears in pastel shades, and at the 100% value we get the most saturated color. If we now start to decrease the V value, we get a darker and darker color, and finally black.

2.4.6 LCH color system

This is a perceptual color system that is somewhat similar to the HSV color system. Its name comes from the initial letters of the English words Lightness, Chroma, Hue. Lightness and Hue are similar to the Value and Hue properties of the HSV color system, and Chroma is a color saturation-like characteristic, just like Saturation. So colors in this color system are described by three properties similar to those used in the HSV color system.

2.4.6 HSL color system

Hue, Saturation, and Lightness are the three characteristics. Colors are described in this color system using three properties similar to those used in the HSV color system.

2.4.7 CIELAB or L*a*b*

The term “L*a*b*” should be distinguished from Lab without the asterisk, because it means something different. Nevertheless, it is also common to write it without the asterisk. The problem is that due to the complexity of our vision, mixing two colors selected in the RGB (or HSV) system cannot be described mathematically. The color calculated and displayed by the computer does not match what we would experience in practice if we mixed those colors. Unfortunately, not all problems can be solved at once. Either the lightness value of the result is good, and the hue is distorted, or the hue is accurate, but the lightness value is not accurate. In the L*a*b* model, the hue is accurate, and the lightness values are distorted.

The L*a*b* color space is based on the difference of opposing color pairs. It uses the four unique colors of human vision: red, green, blue, and yellow. The channels of the L*a*b* color space are: “L*”, as the perceptual lightness value, “a*”, as the difference value of green and red, and “b*”, as the difference value of blue and yellow. The values of the “a*” and “b*” color channels can be negative or positive. In the diagram of the CIE XYZ 1931 color space above, we can see that these color pairs are located opposite each other, which is why we can express with a single numerical value how green or how red, or how yellow or how blue a color is. If the values of the channels “a*” and “b*” are equal to 0, then L*=0 stands for black, L*=100 stands for white, and the intermediate values of L* produce shades of gray. Regarding L*, the value of 100 is usually considered the maximum. If we change the “a*” channel value in a negative direction, we get an increasingly greenish shade. If we change the “a*” channel value in a positive direction, we get an increasingly redder shade. With negative values of the “b*” channel, the color becomes increasingly blue, and with positive values, it becomes increasingly yellow. By using L*a*b*, the colors seen on the screen will be accurate, but the distortion of the brightness values can be easily corrected with the help of the histogram.

In connection with the L*a*b* color space, we can encounter the so-called Munsell correction in processing programs, which can be used to minimize any color shift that may appear. This may not be named in the programs, but we can simply turn on the Prevent color shift option.

2.4.8 Hue, color wheel

Let’s look at the spectrum of sunlight again. When sunlight is broken down into components using a prism, we get a series of monochromatic (single-color, single-wavelength) components. So the spectrum shown in the figure above consists of a succession of monochromatic components. The spectrum of sunlight is continuous, meaning that it contains components of all wavelengths within the entire wavelength range.

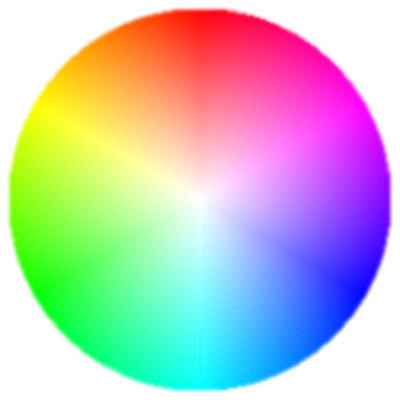

Color wheel

In the color wheel, this spectrum containing only monochrome colors is represented in the form of a circle or ring, and for the sake of continuity between red and violet, we supplement it with the color magenta (and its transitions towards red and violet). In fact, we supplement it with the secondary colors shown along the straight part at the bottom of the CIE XYZ 1931 color space diagram. This way, the transition will be continuous without any jumps. Magenta is not a monochrome color, but a mixed color. If we look at the diagram above as a clock face, we can see the color magenta at about 2 o’clock.

The monochrome colors of the sunlight spectrum, supplemented with the color magenta, are called hue. So, on the color wheel above, we can see hue. Notice that on this color wheel we only see hue, there is no white in the center, and the saturation of the colors does not change along the radius of the circle (if this were not the case, we would see not only hue, but also shades of color in the color wheel). The colors of hue are called pure colors. All colors are equal in the color wheel.

Hue: the pure colors red, orange, yellow, green, cyan, blue, purple, and magenta, and the continuous transitions between adjacent colors; but only the pure colors. These can be seen in the color wheel above.

If we lighten the red color, we get a pink color, which has a red hue. If we darken it, we get a dark red color, which also has a red hue. Mixed colors can have multiple hues, for example, brown can have different shades, and its hue can also be orange or red.

2.4.9 Terms used when describing and modifying colors

Different color systems use different concepts to accurately describe colors and their lightness. These are the following:

Hue: These are pure colors with a continuous gradient, depicted in a color wheel. A hue is a color in this color wheel.

Chromaticity, Chroma: An objective measure of the quality of a color, independent of its lightness. Similar to saturation.

Saturation: The color of an area, taking into account its lightness.

Luminance: Luminance is a property of visual frameworks, and in colloquial terms, it is a concept similar to lightness.

Brightness: This is a concept similar to lightness.

Lightness: Lightness is the perceptual, non-linear equivalent of brightness.

Brilliance: The brightness of an area relative to the brightness of its surroundings.

The exact scientific definition of each concept contains significant differences, but my book is intended for photographers and not physicists, and therefore generally contains significant simplifications and inaccuracies. Here too, I will make a major simplification. Brightness, luminosity, clarity, radiance are approximately what we call simply lightness in common parlance, and I will often use this. Brightness is a characteristic value of how much a given subject rises and shines from its environment. Hue is the pure colors red, orange, yellow, green, teal, blue, violet and magenta, and their transitions on the color wheel. Saturation and chromaticity are somewhat similar concepts, we can use the concept of saturation as a simplification. The point is to have a general understanding of these concepts and how they resemble our everyday concepts of color, because then, when processing the raw image, we will know what property of the image a given control changes. The goal is not scientific accuracy, but rather general understanding.

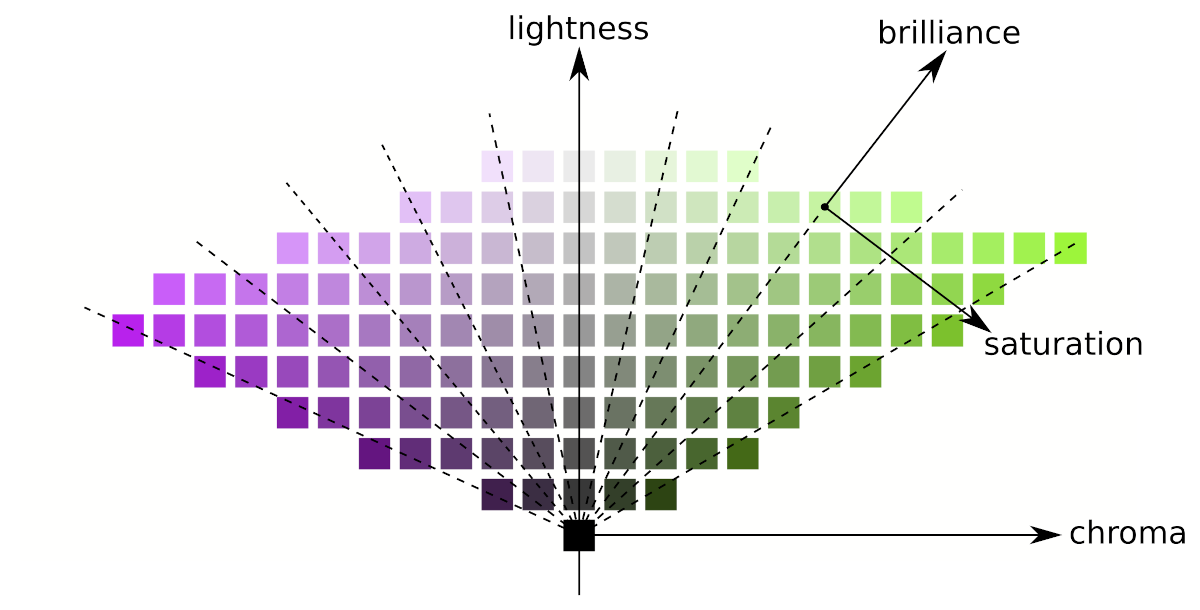

For better understanding, let’s look at the figure below.

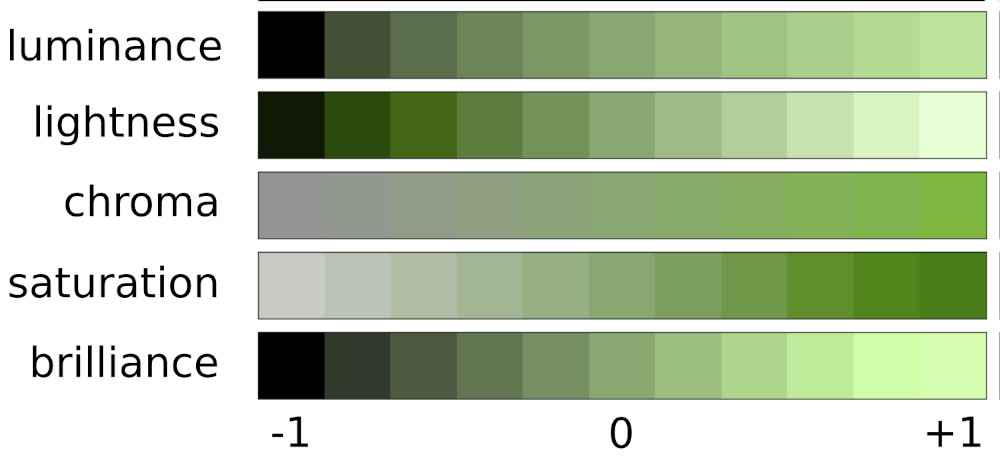

In the figure, lightness, chroma, saturation, and brilliance are depicted in the JzAzBz color space, which is a perceptual color space suitable for high dynamic range (HDR) image information.

In the figure, a black square is shown in the bottom center. The upward arrow indicates that the lightness increases from the black square upwards, i.e. above the black square we can see an increasingly brighter neutral gray square (free of discoloration). The lightness value increases from bottom to top for each column in the figure.

The more we increase the chroma, the further away from the center column the result will be, no matter which row we look at. Squares within a column are of the same chroma (but of different lightness).

The lines connecting points of equal saturation are slanted, and some are drawn with dashed lines. The brillance increases along the slanted dashed lines. Changing the saturation changes the angle of these slanted lines. Moving them in the direction of the arrow in the figure increases the saturation.

Lightness and brilliance are similar characteristics, both of which are about lightness in some sense.

Lightness and chroma together describe the same reality as brilliance/brightness and saturation together. Chroma varies along a constant lightness, saturation along a constant brightness/brillance. The reverse is also true: lightness varies along the same chroma, brightness/brilliance along the same saturation.

Let’s look at the figure above, where we can observe the changes in luminance, lightness, chroma, saturation, and brilliance. Notice how similar the changes in luminance, lightness, and brilliance are, and how similar the nature of the changes in chroma and saturation are.

2.5 Tones

The tones of an image are about lightness values, not colors. Colors (including gray) also have lightness values, lighter and darker tones. These lightness values are called tones.

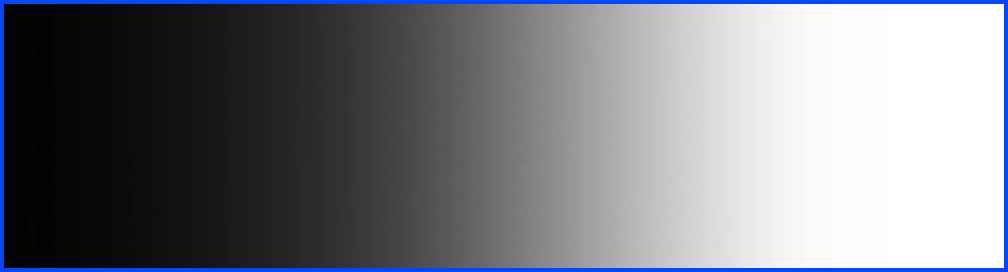

The full tonal range from the darkest to the lightest tone

In photography (image processing), the entire tonal range is usually divided into five parts:

- Shadows: the darkest tones. This is what we call the darkest parts even if they are not actually shadows.

- Dark tones: the range between shadows and midtones.

- Midtones: the middle tonal range.

- Light tones: the range between midtones and highlights.

- Highlights: the lightest tones.

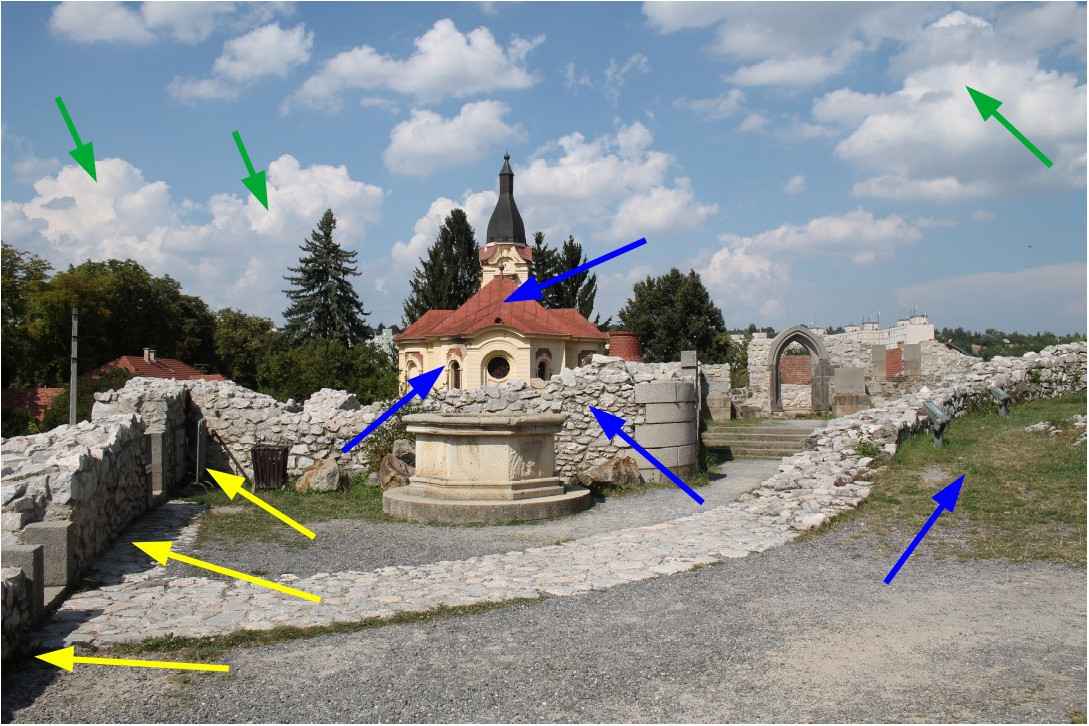

Highlights, midtones, shadows

In the image above, I’ve marked some areas with arrows. Green arrows indicate highlights, blue arrows indicate midtones, and yellow arrows indicate shadows.

2.6 Dynamic range (tonal range), contrast

Dynamic range (tonal range) is very important for editing raw files, so we need to deal with it in more detail. A significant part of our interventions are related to tones, aimed at modifying, compressing, and stretching tones.

The dynamic range

- the photo subject, or

- data recorded by the camera in raw format, or

- the resulting photo

the difference in brightness between the lightest and darkest parts, expressed in exposure value.

Maximum dynamic range is the maximum possible difference in brightness between the brightest and darkest parts, expressed in exposure value.

In essence, a concept similar to dynamic range (tone range) is contrast, which is the difference in brightness between the lightest and darkest parts of a certain part of the image, or of the entire image. If the difference in brightness is large, then the contrast in that part of the image, or of the entire image, is high; otherwise, it is low.

The maximum dynamic range of the landscape being photographed can reach 20 stops. The maximum dynamic range that cameras can record in raw format is technically 12-14 stops. The maximum dynamic range that can be recorded in a commonly used 8-bit per color channel JPEG image file is technically about 9 stops.

The dynamic range of real-world photographic subjects is often not very large, but in many cases it is very large. A low dynamic range is not a technical problem, but a high dynamic range can far exceed the dynamic range that our camera can capture.

An 8-bit JPEG image per color channel can in practice transmit a smaller dynamic range (about 9 exposure values), the dynamic range of the raw file can theoretically be larger, with a much higher resolution (12 or 14 bits), i.e. even very small differences in brightness can be distinguished. This means that the raw file is capable of storing much more information than the JPEG image. It is important to understand that the larger dynamic range that can be stored in the raw file is only a theoretical possibility. If the dynamic range of the subject is small, then only a small dynamic range will be stored in the raw file, but it will also be stored in very small steps, at high resolution.

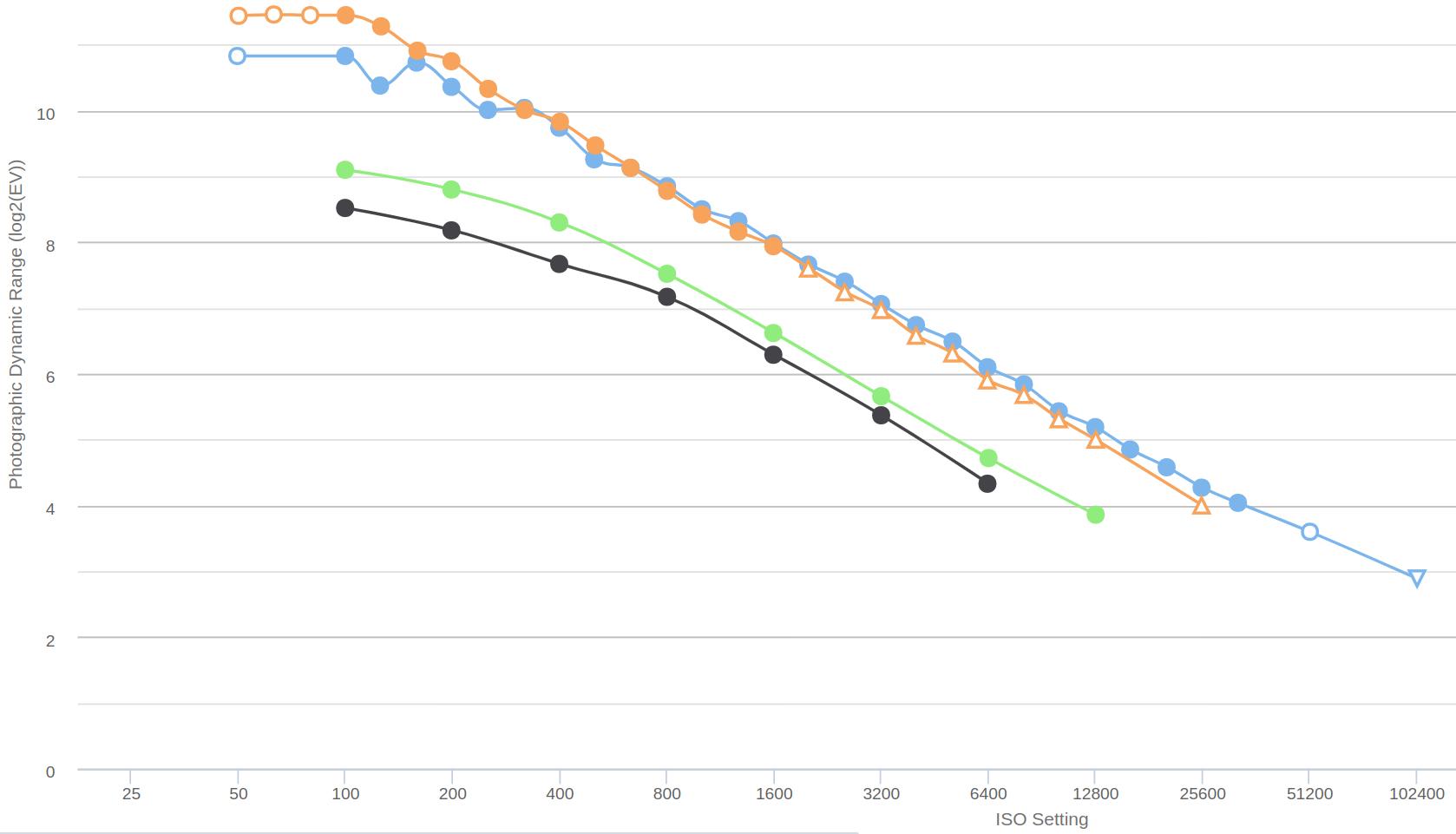

In the table below, we look at the maximum dynamic range of the Canon EOS 5D Mk IV (full-frame) and the Canon EOS 750D (APS-C) body, based on measurements by dxomark.com, as a function of the nominal ISO sensitivity, expressed in exposure value:

| ISO | Canon EOS 5D Mk IV | Canon EOS 750D |

|---|---|---|

| 100 | 13.59 | 11.96 |

| 200 | 13.41 | 11.8 |

| 400 | 12.84 | 11.5 |

| 800 | 12.18 | 10.9 |

| 1600 | 11.46 | 10.24 |

| 3200 | 10.66 | 9.38 |

| 6400 | 9.82 | 8.49 |

| 12800 | 8.85 | 7.23 |

| 25600 | 7.83 | 6.62 |

| 51200 | 7.03 | - |

| 102400 | 6.18 | - |

At a nominal ISO 100 sensitivity, the Canon EOS 5D Mk IV camera has a maximum dynamic range of 13.59 stops, which drops to 7.83 stops at ISO 25600, and finally to 6.18 stops at ISO 102400. The Canon EOS 750D camera has a maximum dynamic range of 11.96 stops at ISO 100 and 6.62 stops at ISO 25600. We can see that at the same nominal sensitivity, the full-frame camera has a higher maximum dynamic range. The dynamic range decreases significantly as the ISO sensitivity increases.

Now let’s look at the camera’s real dynamic range.

The dynamic ranges measured by DxOmark look very nice. Unfortunately, however, these are some kind of absolute maximums that are technically possible. However, the photographer is interested in a practical, real dynamic range, not a theoretical value.

The camera’s truly usable dynamic range is limited by clipping in the brightest tones and noise in the darkest tones.

Determining the practical dynamic range of a camera is subjective because it also depends on how much image noise is allowed in the darkest tones, how much clipping is allowed in the lightest tones, and how much discoloration is allowed due to clipping of a color channel.

Also very interesting in terms of real dynamic range is the website https://www.photonstophotos.net, where we can see the maximum usable dynamic range of many camera types as a function of ISO sensitivity. The website calls the usable dynamic range “photographic dynamic range”.

Source: https://www.photonstophotos.net/Charts/PDR.htm

The figure above shows the dynamic range of two full-frame (Canon EOS 5D Mark IV - blue, and Nikon D800E - orange) and two APS-C (Canon EOS 1100D - black, and Canon EOS 750D - green) cameras, according to the conditions specified by the author of photonstophotos.net.

Here too we can see the advantage of full-frame cameras. Increasing the ISO sensitivity significantly reduces the usable dynamic range.

In this video, Andy Astbury shows us how we can measure the maximum usable dynamic range of our own camera in a very simple way. He measured this himself in the video for the Nikon D800E 36 MP full-frame camera.

Andy Astbury measured at the lowest ISO setting. He considered the upper limit of the truly usable dynamic range to be the exposure at which there was no clipping at all in the raw data, and the lower limit to be the exposure at which there was no noise at all, even at high magnification. You have to determine the exposures corresponding to the lower and upper limits, then calculate how many stops there is between the two exposures, and that is the truly usable dynamic range. The camera should perform best at the lowest ISO setting, so Andy Astbury’s strict criteria are not excessive.

The Nikon D800E camera has a dynamic range of 14.3 stops at the lowest ISO, as measured by DxOmark, while Andy Astbury measured a truly usable dynamic range of 8.3 stops. That’s a huge difference.

I wrote the above so that we can see the reality, that we may not have nearly as much exposure value information available when photographing a highly dynamic subject as we think.

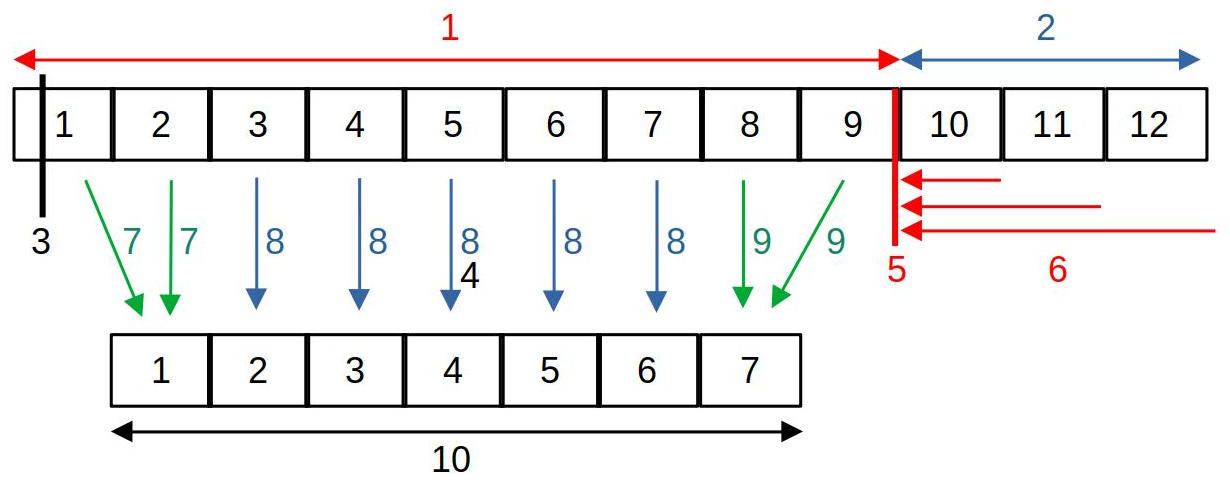

In a theoretical example, let’s see how, assuming an ISO sensitivity of 100, we can map the 9-stop range of raw data for a large subject with a dynamic range of 12 stops to just 7 stops of the JPEG image. Let’s look at the figure below:

- The maximum information that can be extracted from the image sensor is 9 exposure values.

- The dynamics of the subject are greater than this (12 stops)

- Raw black level

- Target gray point (mid-gray)

- Raw white level

- Raw clipping: the information of the 11th, 12th, 13th exposure values is clipped (takes the raw white level value)

- Compressing dark tones

- We map the midtones by exposure value

- Highlight compression

- The gradation range displayed in a JPEG image (which should be 7 light levels)

The above figure shows the case when the subject has high dynamics, the dynamics of which exceed the tonal range that can be transmitted by the camera’s image sensor. Of course, the maximum tonal range that can be transmitted can only be utilized in raw format. Today’s image sensors are technically capable of transmitting a tonal range of 12-14 exposure values, but in reality less than this can be utilized. In the figure, we can see an image sensor capable of transmitting a maximum of 9 exposure values of dynamics, and I have numbered the tonal range for each exposure value. However, the subject has a dynamics of 12 exposure values, and the JPEG image in our example is only capable of displaying a tonal range of 7 exposure values. The fundamental question is what and how should be included in the 7 exposure value tonal range of the JPEG image from the data containing 9 exposure values of dynamics, and what should happen to the 10th, 11th, 12th exposure values that exceed the camera’s tonal range.

The figure shows the raw black level. The raw black level defines the lowest brightness value from which the data in the raw file can be used. Values below this are not used during processing, they are considered the same as the raw black level value (even though they are smaller than it), in other words, they are clipped.

In the figure, the raw white level is represented by the vertical red line at the end of the 9th light level. The raw white level determines the lightest shade value that can still be used. We can see that the subject has a shade range of 12 light levels, which is beyond the dynamics that can be transmitted by the sensor. Values above the raw white level take on the value of the raw white level, so clipping occurs.

In principle, we can produce 7 exposure values of data in the JPEG image from a raw file containing 9 exposure values. The figure shows a possible case, namely, we transfer the data between the 3rd and 7th exposure values of the subject to the JPEG image one by one (blue arrows). However, compression occurs for the highlights and the darkest tones, which means that more exposure values of data from the raw file are mapped to a range of fewer exposure values (one in the figure) of the JPEG image (green arrows). For dark tones, more than 1 exposure value of data is compressed, and for highlights, 2 exposure values of data are compressed. It would not be a good method to clip off exposure values that are outside the tonal range of the JPEG image, or to convert them to the extreme values of the tonal range of the JPEG image. Due to compression, tones outside the tonal range of the JPEG image also appear in the image, however, due to the compression in this section, the tone differences between individual parts of the subject will be smaller than they actually are (loss of contrast).

In the figure we can also see the Target gray point (mid-gray), which is theoretically a mid-gray with a brightness of 18%. The Target Gray Point is used to set the brightness at which the mid-gray light data of the raw file should appear in the output (e.g. in the JPEG image).

At the end of the raw file processing, the high dynamic range image data must be converted into a standard dynamic range (SDR) image that provides the usual visual experience, both for display on a monitor and for creating an image file. In other words, we can say that the image data must be made suitable for display. We saw an example of this in the figure above. ART can also be used to create a High Dynamic Range (HDR) image, but I will not discuss this in detail in my book. You can read about it in the ART documentation.

In ART, you can also adjust the (non-raw) black and white levels, which can be used to influence the brightness values in the image at which clipping occurs. Unfortunately, it is easy to cause clipping during processing. If we experience this, we can find out which processing step caused it and take action against it.

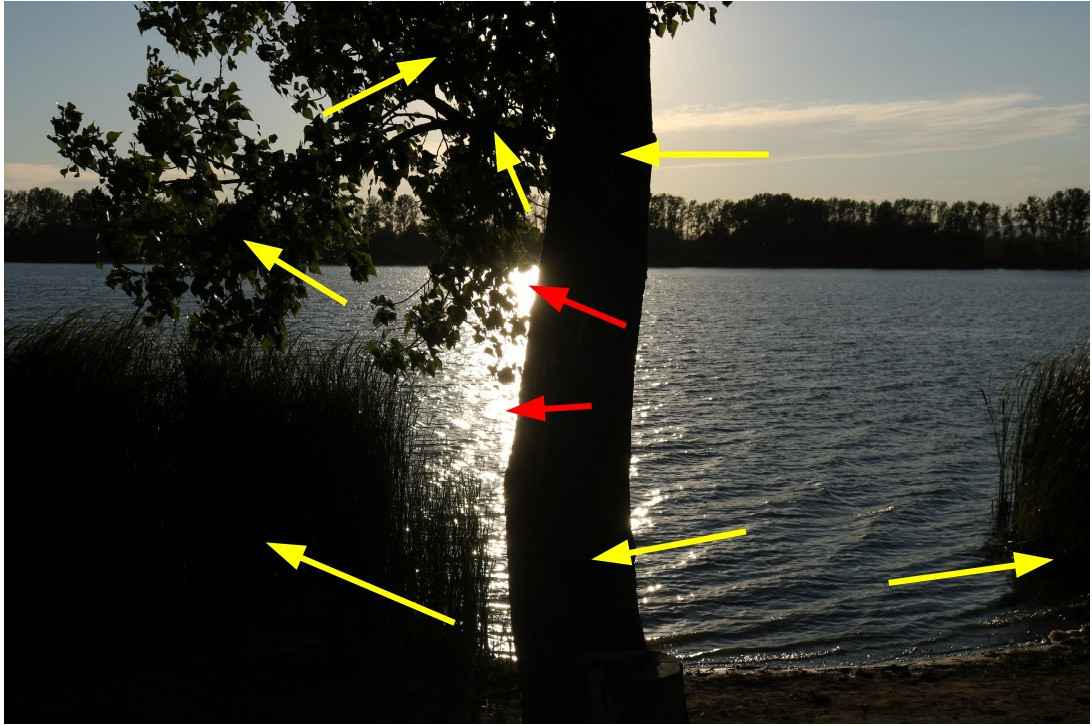

Detailless white (burned out) and detailless black (sunken) details (photo taken by the author)

In the image above, the gradation of the subject is too large. I’ve marked some sunken, detailless black areas with yellow arrows. I’ve marked two detailless, white, burnt-out areas with red arrows.

Our eyes are much more tolerant of clipping in the darkest tones (the blacks without detail) than in the brightest ones (the whites without detail). For this reason, many cameras intentionally underexpose the image by 1/3 to 1 1/3 of a stop. We can also do this by shooting in raw format (if necessary) and intentionally underexpose the subject slightly so that the highlights are not overexposed (clipped) in the raw file. We should strive to create a raw file that we can get the most out of in post-processing.

Now let’s deal with the color image a little. Let’s think about the RGB color system. Not only can clipping occur in all three color channels at the same time, but also in one or two channels. Let’s think about having a [120,130,230] lighter blue color. A certain ratio of the three color channels results in the perceived color. If we lighten this with exposure compensation, then the value of all three color channels starts to increase, and we get to the point where the value of the blue color channel reaches the maximum value, 255. If we lighten it further, then the value of the blue channel cannot increase any further, but the other two will increase, and the ratio of the three color channels changes, which leads to color shift. A typical example of this is light clouds in the sky, which, if clipped, can be pinkish due to color shift. Editing programs protect against this by cutting the other two channels as well, so that we get white, because even that is better than pink. We can also observe the phenomenon on flower petals. In the figure below, the lighter, paler parts of the petals (at the ends of the petals) are caused by clipping the red color channel.

2.7 Opacity

Many editing tools allow you to set opacity, so we need to talk about it. In fact, it is present even in editing tools where we don’t see this term (such as the threshold curve in the Capture Sharpening tool, or the “Strength” slider in some editing tools). Let’s review opacity using the Capture Sharpening tool as an example.

When creating the final image file, the editing tools take effect one after the other, according to the parameters you set. For each editing tool, we have two images:

- One is the input image of the tool, which it receives from the previous tool for further processing.

- The other is the image on which the tool has already had its effect, let’s call this the modified image.

The tool affects all parts of the image equally, for example, the sharpen tool sharpens the entire image equally. In the case of sharpening, the input image is the unsharpened image received from the previous tool, and the modified image is the image obtained after sharpening, which is sharpened equally everywhere.

In many editing tools, depending on some other parameter, it is possible to control how much the effect of a given editing tool is applied to different parts of the image (for example, more strongly in higher contrast areas, less in other places). This can be controlled with opacity. Opacity means the opacity of the image modified by the editing tool, it is given in %, and in many cases its level can be set directly in the editing tool, in other cases, for example, we can control the opacity of certain areas of the image with a curve depending on a certain property of the image. It is a very important point that the level of opacity can be different in different parts of the image.

Let’s imagine that we overlay the modified image with the appropriate opacity on the input image of the editing tool, and see what kind of image we get when we look at these two superimposed images:

- If the opacity of a certain area of the upper image is 0%, then in this part the upper image is completely transparent, as if it were not even there, therefore we will see the lower (input, not yet sharpened) image.

- In areas of the upper image where the opacity is 100%, nothing of the lower (input) image will be visible, we only see the upper (modified, sharpened) image, as if the lower one were not there.

- Between the two extreme values, the higher the opacity value, the more the effect of the upper, sharpened image prevails.

The final output image of the editing tool will be the resulting image of the two superimposed images.

The process of creating the resulting image using the input image and the modified image (taking into account certain parameters, such as opacity) is called blending.

Blending can not only be done in such a simple way, but there are several ways to blend two images, each blending mode can produce different results.

2.8 Feather

Feather is used with masks, the Spot Removal tool, and the Gradient Filter editing tool. Its purpose is to ensure that the effect of a given tool does not end with a sharp boundary line, but rather has a gradual transition towards its surroundings.

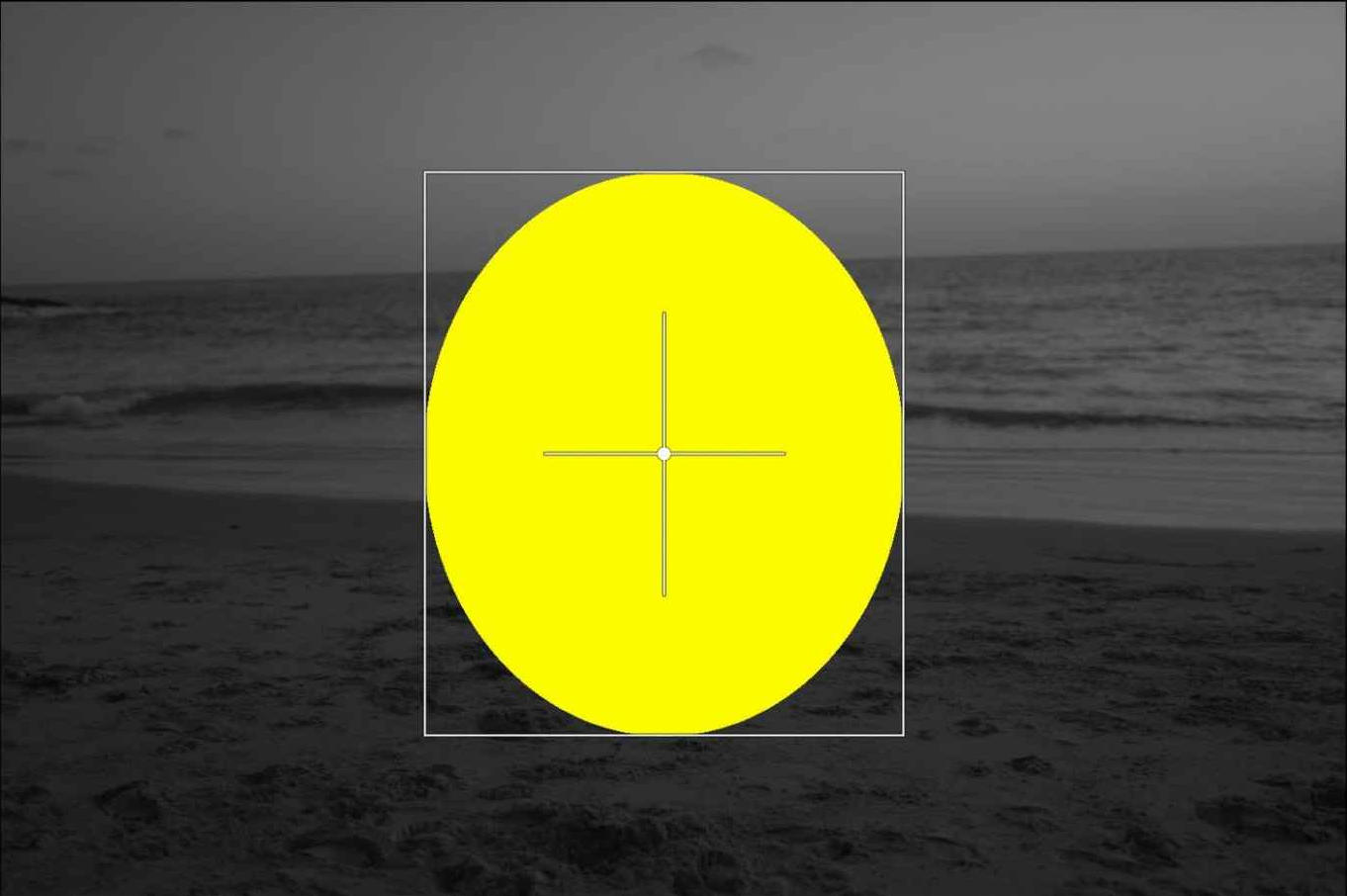

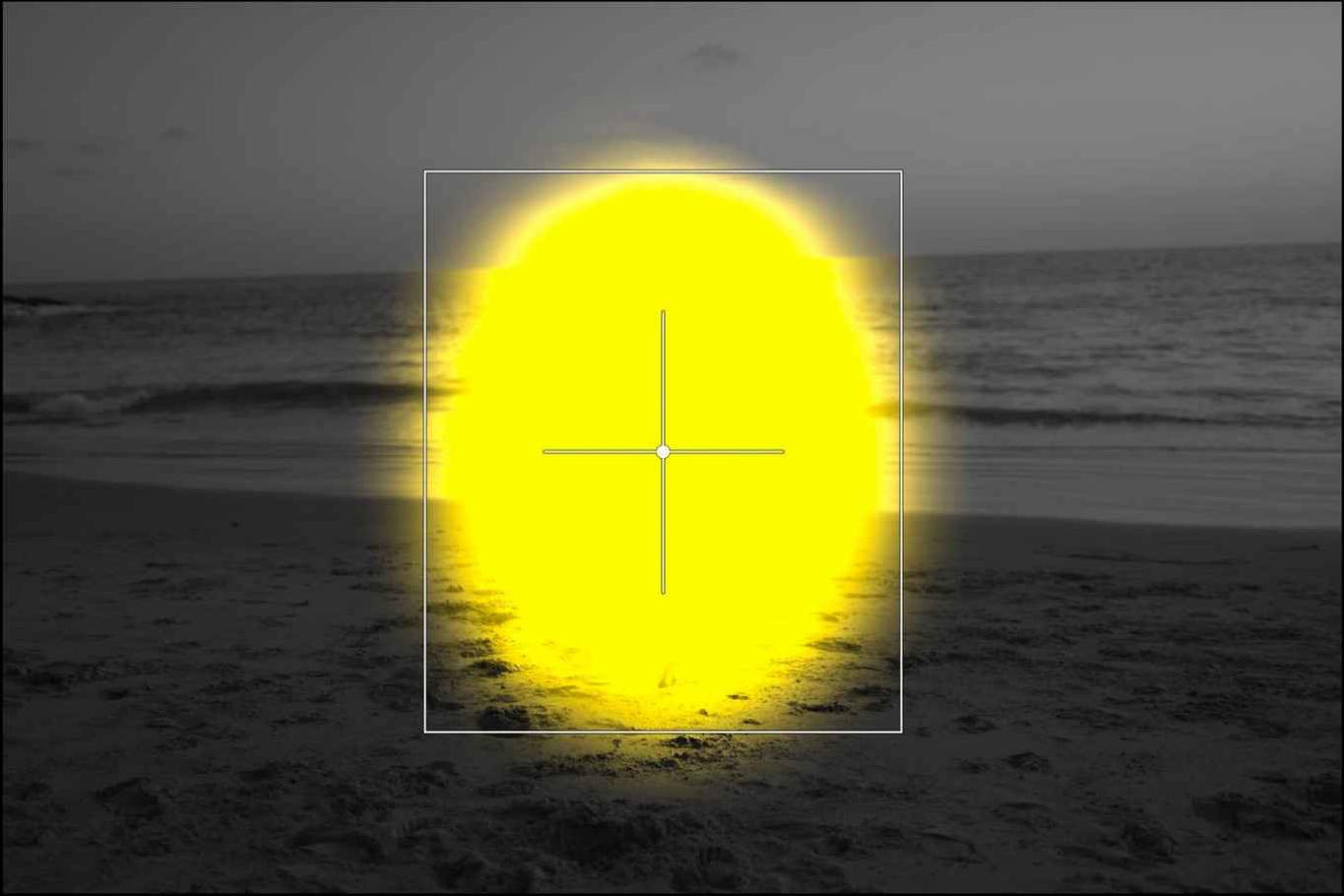

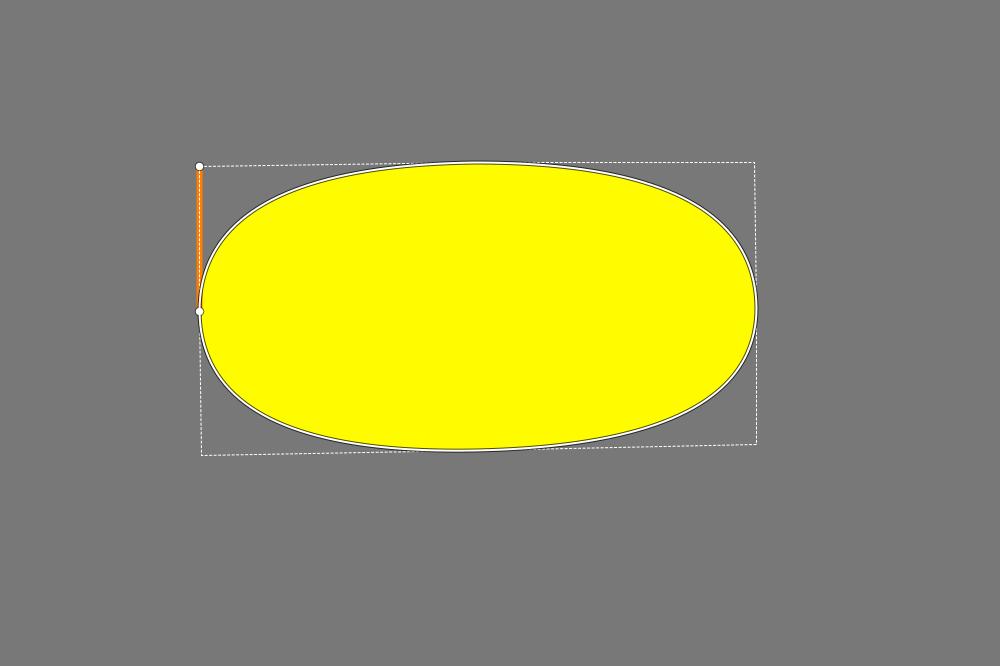

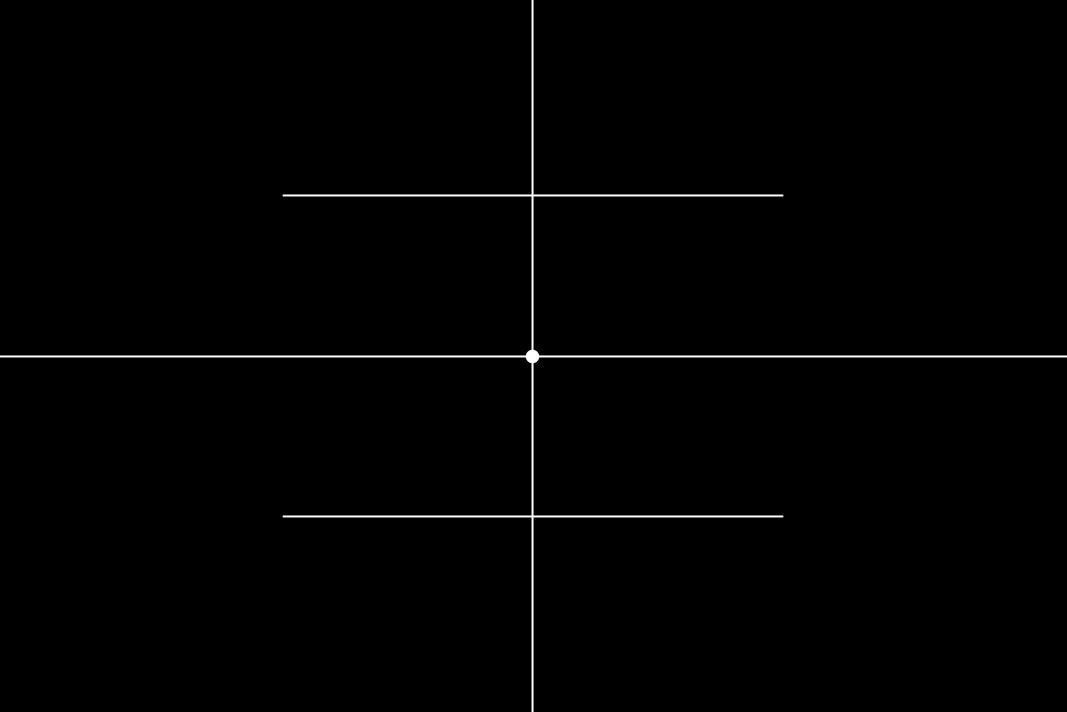

In the image above, we see a yellow mask with sharp edges. We want to brighten the image in the area of the mask.

The center of the image was brightened with a sharp boundary line.

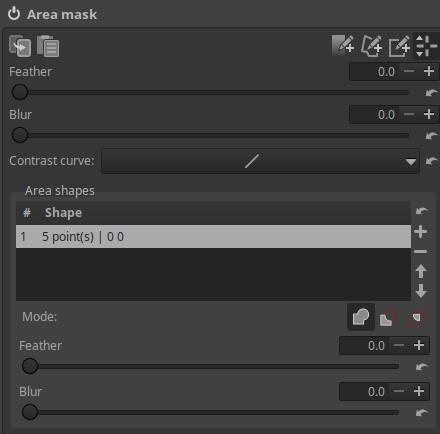

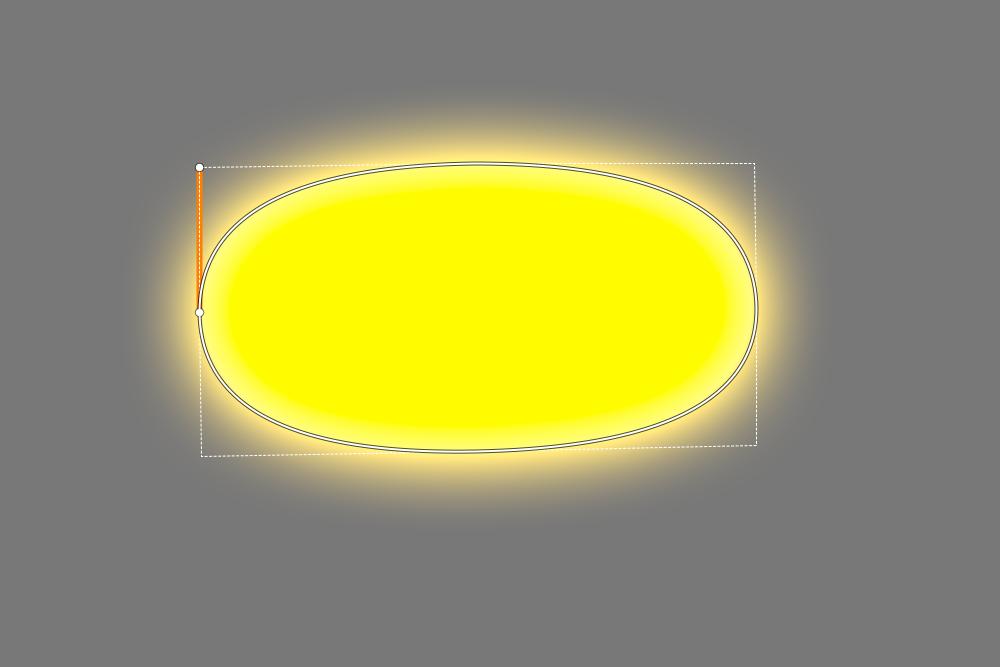

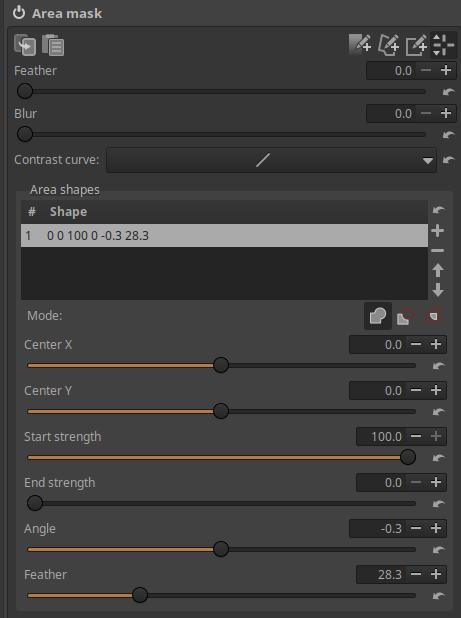

I added feather to the mask.

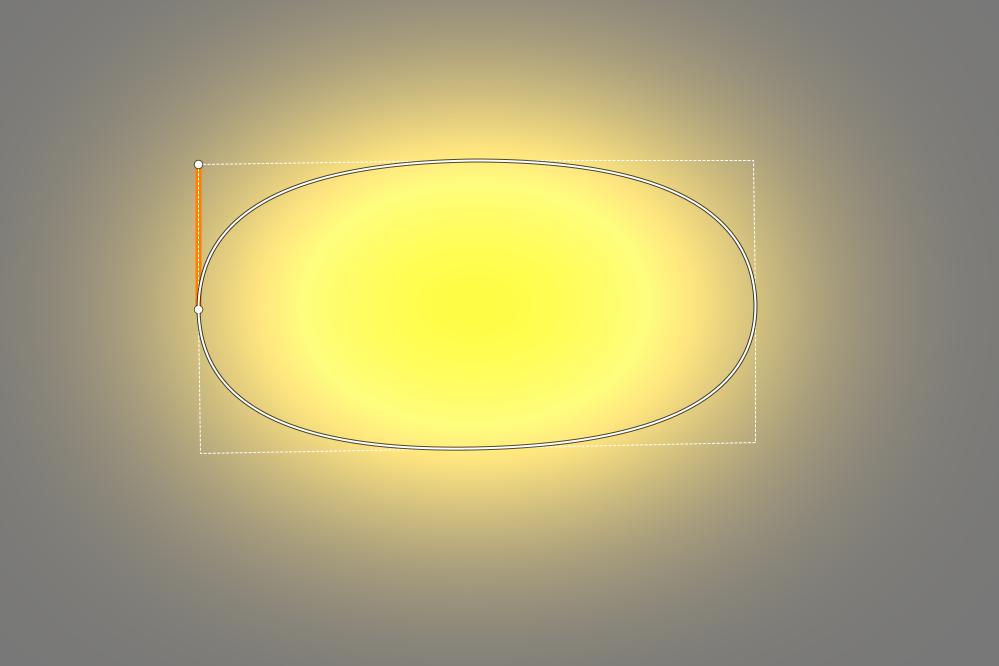

The effect of exposure compensation gradually disappears due to the feather.

2.9 Wavelet decomposition

Wavelet decomposition is a complex mathematical procedure. It can be used to break down an image into multiple levels of detail. Each level contains different levels of detail in the image. For example, at the first level of detail, the program looks at the contrast of the pixels in each 2x2 pixel area of the image, at the second level it analyzes the image by dividing it into 4x4 pixel areas, at the third level it analyzes the area 8x8 pixels, etc. The figures below show the level of detail experienced at the second, fifth, sixth, and eighth levels.

Level 2 only contains very fine details of the image (source: darktable)

Level 5 only contains much larger details, not fine details (source: darktable)

Level 6 only contains even greater detail (source: darktable)

The 8th, last level only contains the largest parts of the image, no fine details (source: darktable)

Wavelet decomposition decomposes the image elements into components of the L*a*b* color space (L*, a*, and b*), and the differences in hue are also displayed at each level of detail.

Since only differences in hue or brightness (gradients or differences) are analyzed at each level, the detail levels do not contain any information if the image is completely uniform in brightness and color. In this case, the differences extracted from each level come from digital noise and changes in contrast (or hue).

The residual image is created by removing the details of the decomposed levels from the original image, and what remains is the residual image. This means that modifications made at a given detail level (contrast, hue, etc.) have no effect on the residual image, and vice versa. We can perform operations not only on individual detail levels, but also on the residual image. It is also possible that if we have changed something at certain levels, we can then make completely different changes at other levels (and the residual image).

By reuniting the detail levels and the residual image, we get the full image back. Leveling allows us to perform certain interventions only at certain detail levels, leaving the other levels and the residual image unchanged.

Wavelet decomposition can be used for several purposes, such as removing image noise, adjusting the contrast and tones of individual levels, blurring or removing unwanted details, changing saturation or colors, sharpening, etc.

If an editing tool’s name or description includes the phrase “by details”, we can almost be sure that it is Wavelet decomposition.

Let’s look at an example based on the darktable user manual. In the figure below we can see a detail of the original image, the problem is the skin defects on the face, which we want to reduce.

Original image (source: darktable)

Level 5 is where skin imperfections are most visible. If we create a blur at this level, skin imperfections will be much less visible. (source: darktable)

The resulting image, which retained fine details and was not affected by the blur (source: darktable)

We applied blur in such a way that it only had an effect on level 5, leaving the other levels unchanged.

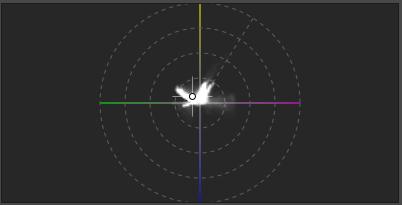

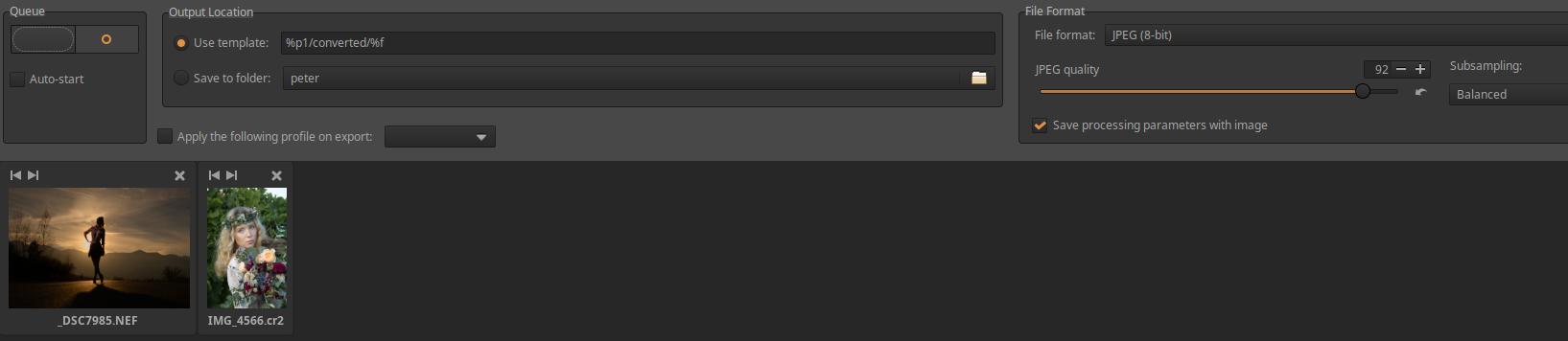

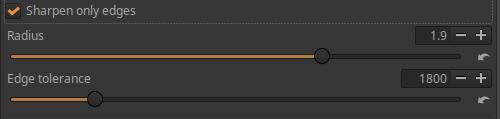

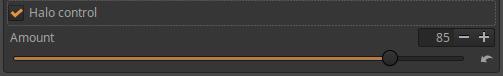

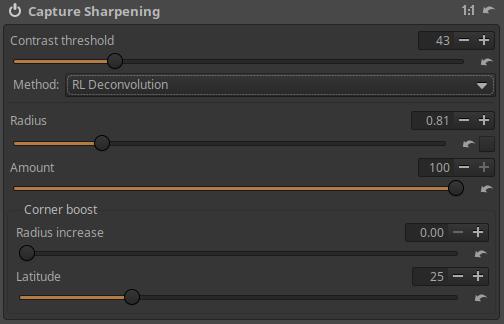

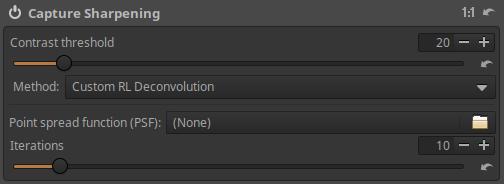

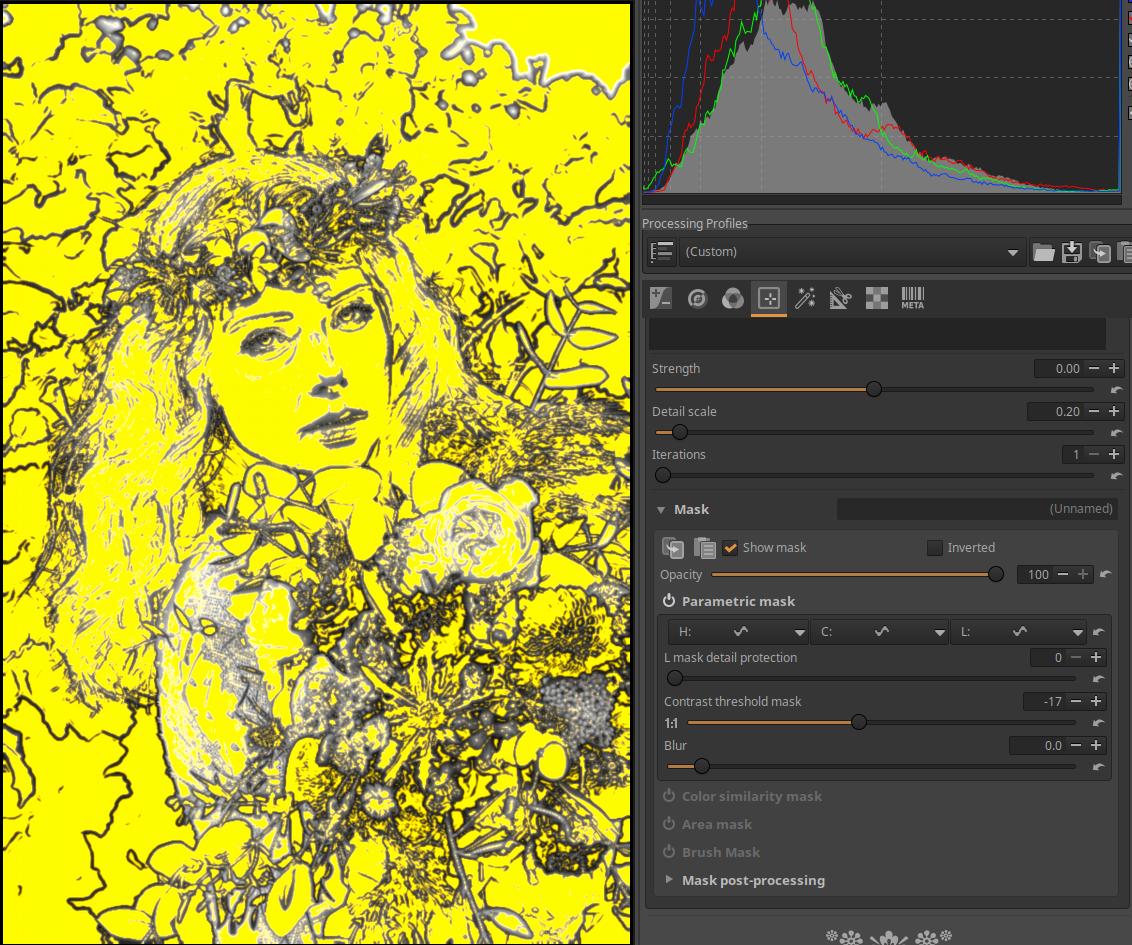

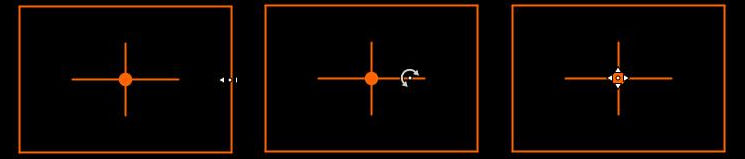

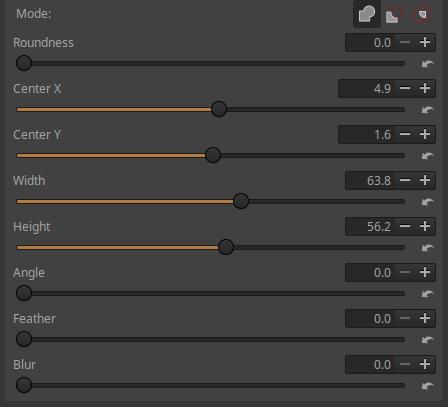

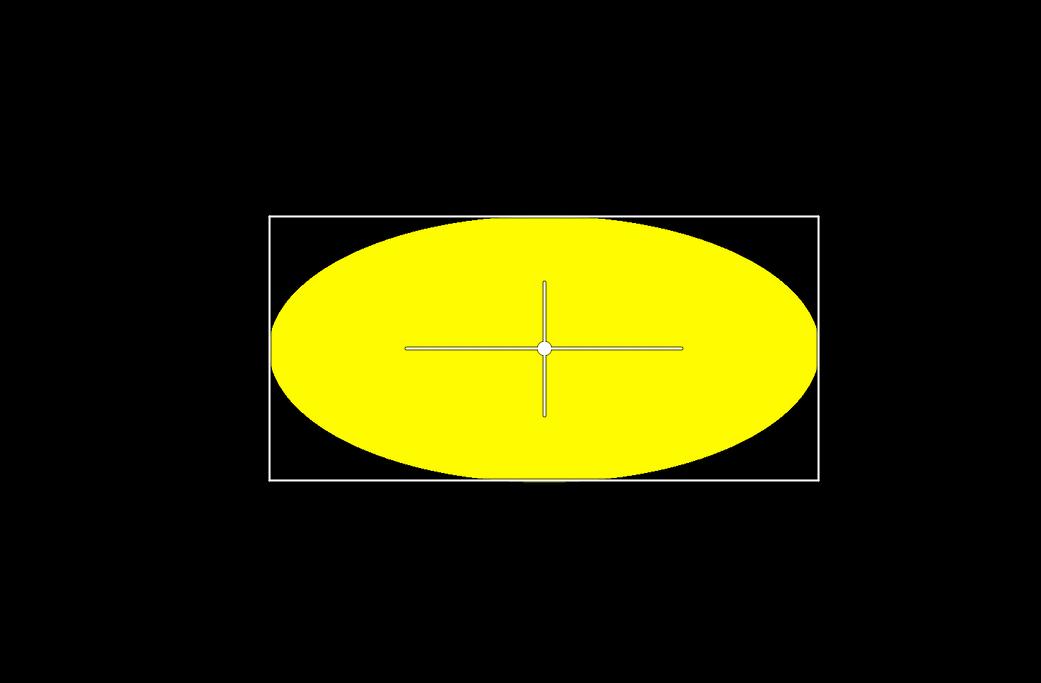

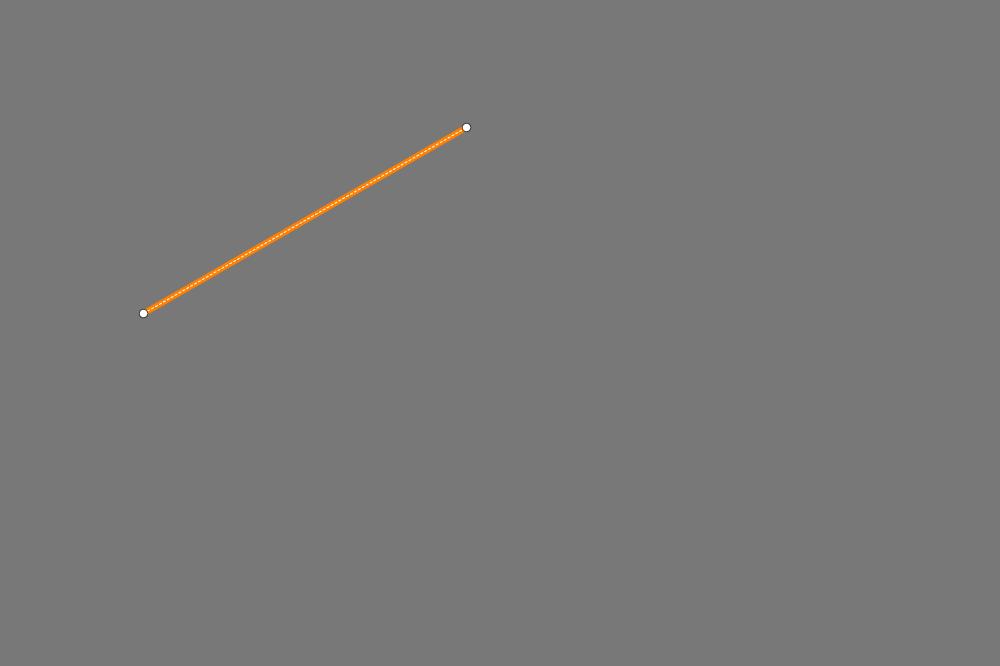

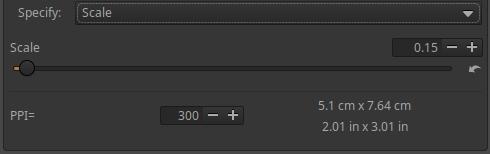

2.10 Capture sharpening procedures